Soldiers Three (1951)

Toronto Film Society presented Soldiers Three (1951) on Monday, January 19, 1987 in a double bill with The Desert Song as part of the Season 39 Monday Evening Film Buffs Series “B”, Programme 5.

Production Company: MGM. Producer: Pandro S. Berman. Director: Tay Garnett. Screenplay: Marguerite Roberts, Tom Reed, Malcolm Stuart Boylan, suggested by the Rudyard Kipling stories. Photography: William Mellor. Music: Adolph Deutsch. Editor: Robert J. Kern.

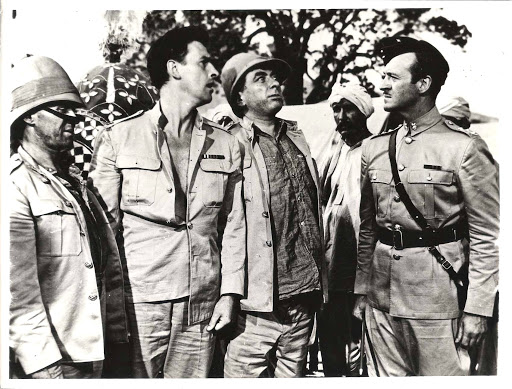

Cast: Stewart Granger (Private Archibald Ackroyd), Walter Pidgeon (Colonel Brunswick), David Niven (Captain Pindenny), Robert Newton (Private Jock Sykes), Cyril Cusack (Private Dennis Malloy), Greta Gynt (Greenshaw), Frank Allenby (Colonel Groat), Robert Coote (Major Mercer), Dan O’Herlihy (Sergeant Murphy), Michael Ansara (Manik Rao), Richard Hale (Govind Lai).

To-night’s programme has been publicized as a tribute to two of Hollywood’s most reliable second-string directors, Tay Garnett and Bruce Humberstone. It also could have been announced as a screening of two 1950’s re-makes executed with a relatively large budget.

One can easily imagine the meeting where MGM’s top executives came up with the idea of making Soldiers Three. The studio had signed in 1950 a seven-year contract with the virile British actor, Stewart Granger (born James Stewart!), who helped make their production of King Solomon’s Mines a big commercial and critical success in the same year. Now they had to get the greatest possible mileage out of their new hot property. What better way to do it than throw him into a tried and true vehicle for a British cast, the Rudyard Kipling chestnut, Gunga Din, about three high-spirited and undisciplined soldiers in Kipling’s India? After all, the 1939 film’s original producer, Pandro S. Berman, was now a senior MGM contract employee, and there should be no trouble in finding convincing British or pseudo-British actors to fill out the rest of the cast. For instance, wasn’t their veteran star Walter Pidgeon, a Canadian? Isn’t that, in Hollywood eyes, almost the same as being British? Besides, there was plenty of footage of India still available on the lot, left over from the MGM version of Kipling’s Kim. And so on…

The resulting film, directed by Tay Garnett was instantly panned by most critics, who immediately saw the unacknowledged kinship with the acclaimed 1939 RKO classic of George Stevens. Some critics mused about the absence here of the original film’s title-character, and most recoiled from the overacting of its cast, which saw the film apparently as a perfect opportunity for conveying raucous living. But after all, any film which had signed on the outrageously eye-rolling and leering Robert Newton had right from the outset forsaken all claims to subtlety of performance. It was this very dynamism of the cast, though, which pleased the 1951 audiences. Obviously produced for its comic values, Solider Three fulfilled its purpose nicely. Some viewers may have been impatient with the slow-frame episode in which Walter Pidgeon, as an elderly general, introduces the lengthy flashback (i.e., the main part of the film), which explains how he reached that exalted rank in India. Soon after, we are into the world of drinking and brawling which even contained, as the more highbrow critics complained, a scene in which a detail of soldiers loses its clothing and must borrow a lady’s frilly garments. Such was the level to which producer Berman and director Tay Garnett found themselves reduce in their efforts to arouse unrelenting laughter.

Director Garnett (1894-1977) was no longer at the peak of his career, a point which can probably be identified more easily than that of many another Hollywood director. For the only one of his 42 feature films which can now qualify as an unassailable classic is his 1946 version of The Postman Always Rings Twice with John Garfield and Lana Turner. Other of his better remembered films are Her Man and One Way Passage from the early 1930s, Seven Sinners and Cheers for Miss Bishop from the early 1940s, and his two Greer Garson vehciles, Mrs. Parkington and The Valley of Decision of 1944 and 1945 respectively. For both of these films, the gracious Garson received her customary Oscar nominations of the period. This in spite of the fact that her heavy-drinking, rowdy director was much more at home in the world of John Wayne (Seven Sinners) or our Soldiers Three. In later years, Garnett would find a comfortable niche for himself directing episodes of such macho television shows as “Wagon Train”, “Gunsmoke”, “Rawhide”, “The Untouchables”, “Bonanza” and “Death Valley Days”.

And how did Granger fare in the old Cary Grant role in Soldiers Three? Very well indeed, although certain audiences still preferred the Granger of the British melodramas like Madonna of the Seven Moons or Fanny by Gaslight (both 1944). The seven years at MGM would still be highlighted by Scaramouche (1952–shown in our Film Buff Series “A” this year) and Young Bess (1953), the latter of which starred him opposite his beautiful young wife of the hour, Jean Simmons, in the title role. After MGM, Granger appeared in the 1960s in many a best-forgotten swashbuckler filmed in Europe. A few years ago, still a dashing figure, Granger surfaced yet again to promote his autobiography.

David Niven, who appears here as an adjunct to Walter Pidgeon, was at one of those frequent low ebbs in his lengthy career. He hadn’t had a truly successful film since The Bishop’s Wife (1947–also shown in our Film Buffs Series “A” this year). And in that one, he had taken second male billing to Cary Grant. Two years after Soldiers Three, his career would take an upswing with The Moon is Blue, and with Around the World in 80 Days (1956), he would begin a roll which would include his Oscar-winning performance in Separate Tables (1958). As Richard Sater put it, “David Niven survived more bad pictures than any other major actor without loss of reputation–a remarkable achievement.”

Notes by Cam Tolton

Leave a Reply