The Desert Song (1953)

Toronto Film Society presented The Desert Song (1953) on Monday, January 19, 1987 in a double bill with Soldiers Three as part of the Season 39 Monday Evening Film Buffs Series “B”, Programme 5.

Production Company: Warner Brothers. Producer: Rudi Fehr. Director: Bruce Humberstone. Screenplay: Roland Kibbee, based on the play by Lawrence Schwab, Otto Harbach, Oscar Hammerstein II, Sigmund Romberg and Frank Mandel. Photography: Robert Burks. Editor: William Ziegler. Musical numbers staged and directed by: LeRoy Prinz. Musical Direction: Ray Heindorf. Musical Adaptation: Max Steiner.

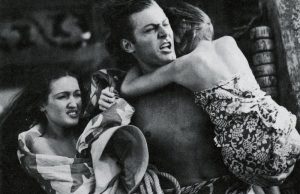

Cast: Kathryn Grayson (Margot), Gordon MacRae (Paul Bonnard), Raymond Massey (Youssef), Steve Cochran (Captain Fontaine), Ray Collins (General Birabeau), Dick Wesson (Benjy), Allyn McLerie (Azuri), Paul Picerni (Hassan), Frank De Kova (Mindar).

The lavish 1953 version of The Desert Song was actually the third filming of the 1926 operetta by the Warner Brothers Studio. The first version, shot in 1929, is historically important as the first operetta ever filmed in the sound era. Quite naturally, after its success with The Jazz Singer, the studio was anxious to find musicals to film. Under Roy Del Ruth’s direction, the story of thee mysterious leader of the oppressed desert Riffs and the general’s daughter proved to be very entertaining, with John Boles and Carlotta King in the leading roles. Even then, though, Del Ruth was unable to disguise some of the silliness of the plot, and audiences laughed in unexpected places.

The second version, restored and revived at this year’s Festival of Festivals, is considered by many to be the best version of the three. Filmed in colour in 1943, this version introduced a timely 1939 setting, complete with Nazi and anti-Nazi intrigue. Dennis Morgan was a stalwart “Red Shadow”, and Irene Manning a memorable Margot, under Robert Florey’s direction.

In 1953, for some unexplained reason, The Red Shadow’s name has been changed to El Khobar. As played by Gordon MacRae, the part is served with more respect than it deserved on its third outing. But both MacRae and co-star Kathryn Grayson are in fine voice here, and have the still wonderful score to render perhaps even more wonderful than ever.

Director Bruce Humberstone was a veteran of many Hollywood musicals. But most of his work had been done at Twentieth Century-Fox, where he had directed their various cycles of blonde musical stars: Sonja Henie (Sun Valley Serenade, 1941); Alice Faye (Hello Frisco Hello, 1943); Betty Grable (Pin-up Girl, 1944). At Warners, he had just directed Virginia Mayo (with Ronald Reagan) in the 1952 re-make of The Male Animal, She’s Working Her Way Through College. Humberstone showed considerable restraint (or lack of imagination) by filming the whole of The Desert Song straight and avoiding intentional camp, although one might indeed wonder what his intentions were in casting Allyn McLerie (the Amy of the Ray Bolger Where’s Charlie?) in the role of an exotic dancer.

Gordon MacRae was in transition here between his Doris Day nostalgia musicals (Tea for Two, 1950, On Moonlight Bay, 1951, and By The Light of the Silvery Moon, 1953) and his blockbuster Rodgers and Hammerstein films (Oklahoma, 1955, and Carousel, 1956). Kathryn Grayson, born Zelma Hedrick in 1922, had been, with Judy Garland, the number one singing star at MGM during the 1940s. Much of her success she owed to producer Joe Pasternak, who had come to MGM from Universal, where he had nurtured the career of Deanna Durbin. Grayson’s unexpected appearance at Warner Brothers was indicative of the turn her career was taking in the 1950s. For her place at MGM was being usurped by Ann Blyth, whose singing voice was not nearly so spectacular as Grayson’s, but whose acting talent was undoubtedly superior. (For example, Blyth received an Oscar nomination for Mildred Pierce, 1945.) Kathryn Grayson’s ventures into dramatic roles were handicapped by the same limited little-girl speaking voice that she shared with a surprising number of her MGM colleagues (Esther Williams, Ava Gardner, Cyd Charisse). Only Elizabeth Taylor seemed able to overcome the handicap sufficiently so as to be taken seriously in dramatic parts. When musicals fell into disfavour in the mid-1950s, it is not surprising that Kathryn Grayson’s film career was over. Grayson’s fans, however, remain legion, and many of them are ready to place alongside such classics as Anchors Aweigh, Show Boat, Lovely to Look At and Kiss Me Kate the splendidly lyrical 1953 version of The Desert Song.

Notes by Cam Tolton

Leave a Reply