Splendor in the Grass (1961) and A Face in the Crowd (1957)

Toronto Film Society presented Splendor in the Grass (1961) and A Face in the Crowd (1957) on Monday, November 3, 1980 in a double bill as part of the Season 33 Monday Evening Film Buff Series, Programme 3.

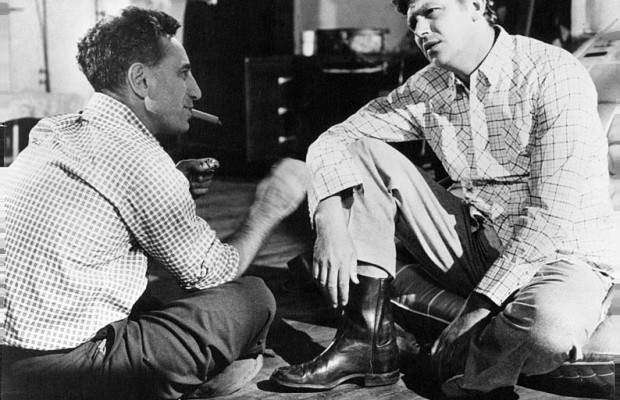

Elia Kazan has been an actor, a playwright, a stage director of the first magnitude, a film maker of international significance, a screenwriter and most recently a novelist. It would seem that the fact that he was demonstrably at home in multiple media made him an object of grudging acceptance, when not out and out denigration, particularly on the part of some film critics whose world does not appear to extend beyond a screening room.

Throughout his career, Kazan has been vitally concerned with the centrality of the work of the writer. He has chosen to involve himself heavily with first-class writers in preparing screenplays for his films and was typically an uncredited co-author of the screenplay. In doing this he did not simply take over a screenplay, and in the ridiculous jargon of Hollywood, “lick it”; rather he involved himself intimately with writers with whom he shared some sensibility and together they created remarkably fine screenplays. In choosing to work so closely with writers who shared his interests, opinions and world view, he might be said to have truly authored some of the most personal and important American films.

Kazan was one of the first American directors to establish his own production unit. Headquartered in New York, this highly skilled production team was largely assembled from personnel whose prior experience had predominantly been in television. In t his way Kazan achieved an exemplary degree of control over his films that was to be obtained by other American directors later.

It is these two major aspects of Kazan’s work in film that has attracted the greatest attention of the newer generation of film=makers. On the other hand, it was Kazan’s remarkable ability to elicit singularly fine performances from his players that has been most consistently praised by critics. This is of course a characteristic of Kazan’s work but the disproportionate attention which it has received probably reflects the inability of most critics to view him as a “true” film-maker. After all, Kazan was not simply a man who came from the legitimate theatre but had founded the Actor’s Studio and continued to be one of the most important stage directors working in the New York theatrical community. In interviews Kazan has consistently distinguished between his work in staging a play and in making a film; he has repeatedly appraised the latter as the most personal of his works.

In understanding Kazan’s world view, it is important to remember that he was born in 19909 and that the issues and opinions of the late twenties and thirties acquired a strong personal relevancy for him that persisted throughout his career. The most obvious aspect of this is his preoccupation with societal conditions, but of equal importance in his multifaceted concern with individual psychopathology. Throughout his films, it is the convergence of these interests which both shape and drive his narratives. Because of these personal preoccupations, Kazan’s films aren’t readily analysed as genre films, and though a number of his films were major commercial successes, a number of them were out of step with the dominant ethos of the times when they were released. This was particularly true of A Face in the Crowd. To a lesser, though still quite noticeable, extent it was also true of Splendor in the Grass.

Many of the reviews that appear when Splendor in the Grass was initially released made the mistake of interpreting the film as saying “Sexual abstinence drives you crazy–if you are a woman.” Kazan’s film is actually far less psychologically naïve than apparently most critics had the background to recognize. With few exceptions, they failed to notice that the apparently “healthy, young girl”, played by Natalie Wood, is profoundly neurotic and is able to maintain her façade of normalcy only so long as she has someone upon whom to focus her maladaptive dependence. Her experience and behaviour become increasingly disturbed and disturbing when the termination of her major supportive relationship with Bud, played by Warren Beatty, leaves her without an appropriate or agreeable partner upon whom to focus her marked need for affection and approval.

Both Splendor in the Grass and A Face in the Crowd were frequently criticised for the way they depicted American society. For instance, Henry Hart wrote in Films in Review concerning A Face in the Crowd, that “Schulberg and Kazan are not depicting truths they have perceived, but a synthetic untruth, reminiscent of the Marxist delusions of the ’30s, and of no intellectual, cultural, or political value, save to those who sek to confuse the American people about themselves, or to those who desire to denigrate the American people before the world.” (1957, pp. 50-51)

At least in part, such criticisms derive from the fact that heroic characters do not appear to resolve the social conflicts against which personal conflicts are enacted in his films. Kazan tends to bring societal and individual disturbances into a tense co-existence with such dramatic force that some people want a happier ending than Kazan can believe in. The triumph of order for Kazan is not found in the ultimate resolution of discord but in the final acceptance of that which can not be changed and the individual power to grow beyond it. The lines from Wordsworth’s “Ode on Intimations of Immortality” which afforded William Inge and Kazan the title of Splendor in the Grass express a philosophy which informs most of Kazan’s films including A Face in the Crowd.

-

Though nothing can bring back the hour

- Of splendor in the grass,

- Glory in the flower,

- We will grieve not, rather find

- Strength in what remains behind.

References: The American Cinema, Andrew Sarris, 1968

Films and Filming, March 1962

The Great American Movie Book, Paul Michael (Editor-in-Chiev), 1980

Kazan on Kazan, Michel Ciment, 1973

Monthly Film Bulletin, December, 1957 & February, 19962

Movie, Winter (#19), 1971-72

Our Inner Conflicts, Karen Horney, ,1945

Sight and Sound, Summer & Autumn, 1957

Working with Kazan, the Wesleyan Film Program, 1973

Research by Helen Arthurs

Written and prepared by Marcia Gillespie and Lloyd Gordon Ward

Whoa all kinds of superb knowledge.

Looks like Bridges and Moore have their tongues firmly in their cheeks right here, with

hammy performances bordering to match the fantasy material.