The Treasure of the Sierra Madre (1948)

By Toronto Film Society on October 21, 2019

Toronto Film Society presented The Treasure of the Sierra Madre (1948) on Sunday, January 24, 1982 in a double bill with The Misfits as part of the Season 34 Sunday Afternoon Film Buffs Series, Programme 7.

Production Company: Warner Brothers. Producer: Henry Blanke. Director: John Huston. Screenplay: John Huston, based on the novel by B. Traven. Photography: Ted McCord. Art Direction: John Hughes. Set Decoration: Fred M. MacLean. Music: Max Steiner. Orchestrations: Murray Cutter. Editor: Own Marks. Assistant Director: Dick Mayberry. Sound: Robert B. Lee. Makeup: Perc Westmore. Special Effects: William McGann and H.F. Koenekamp.

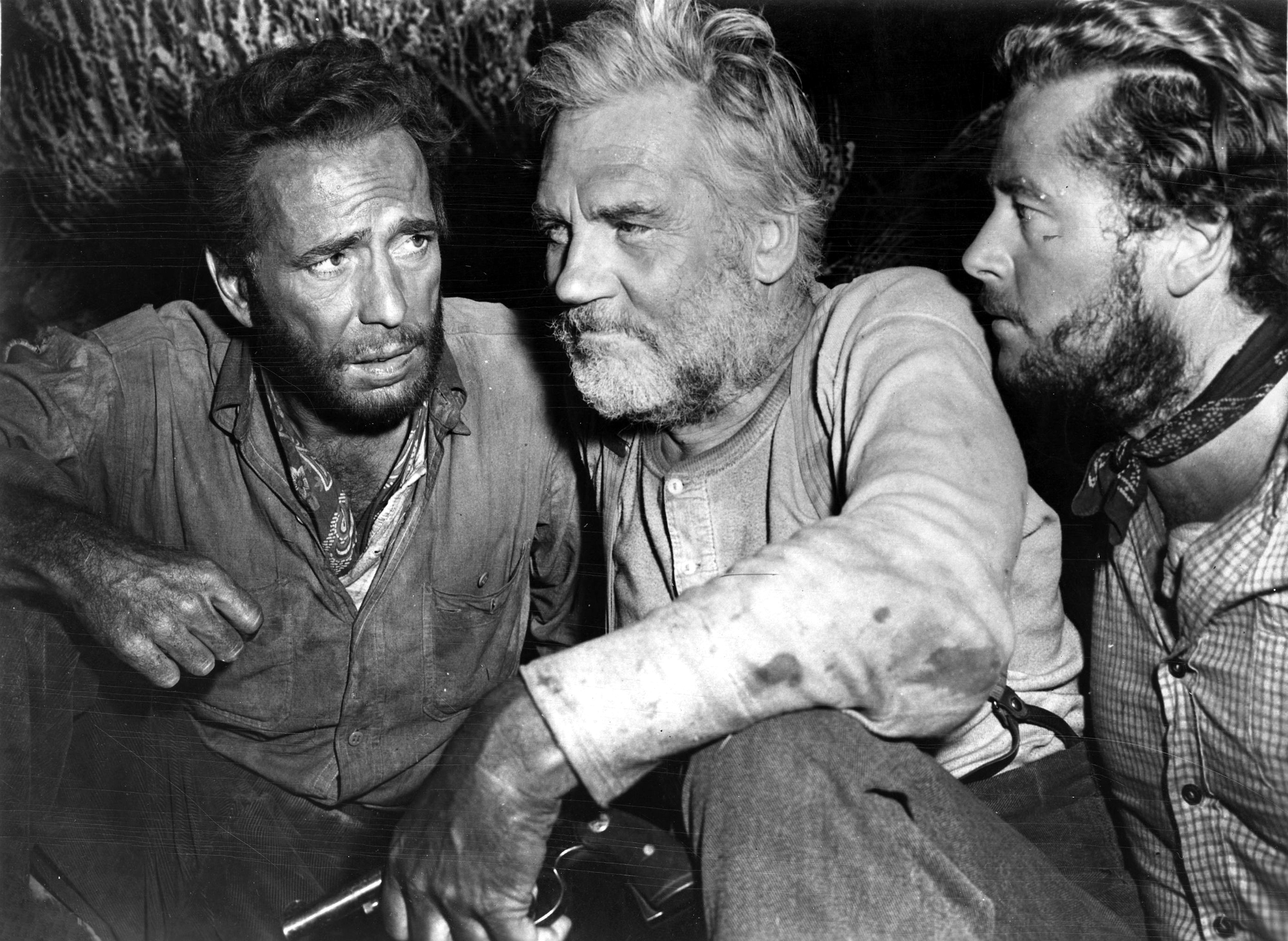

Cast: Humphrey Bogart (Fred C. Dobbs), Walter Huston (Howard), Tim Holt (Curtin), Bruce Bennett (Cody), Barton MacLane (McCormick), Alfonso Bedoya (Gold Hat), A. Soto Rangel (Presidente), Manuel Donde (El Jefe), Jose Torvay (Pablo), Margarito Luna (Pancho), Jacqueline Dalya (Flashy Girl), Bobby Blake (Mexican Boy), John Huston (Man in the White Suit), Jack Holt (Flophouse Bum).

Sierra Madre is throughout a wonderful blend of film crafts. All of them were perfectly focused, through the dominating personality of John Huston, on the objective of portraying what happened to three American bums on a treasure hunt in the wild mountain country of Mexico. In many ways it is a cruelly realistic picture, but it is also full of subtlety. Its characters are neither heroes nor villains, although both heroism and villainy are potential attributes of all of them. A large part of the cast is composed of Mexican natives, semi-professional and amateur actors, as characters in the play they have the complexities peculiar to semiprimitives. The locale of the film is nature at its most desolate and raw. The action is violent. It is, in short, an adventure story rich in tragic and poetic overtones and with a strong undertow of bitter comedy.

The only out-of-tune element is Max Steiner’s score. This is not because Steiner is not a competent film composer. He is, indeed, one of the best, although much of his recent work has been tired. Never can it be said that he earned his reputation by bad performances; nor has he come to be regarded as one of the founding fathers of film music without having made large contributions to its techniques and its literature. Of atmospheric and dramatic music of the plainer sorts he is a real master; and he has a formidable repertory of devices to fit almost any movie situation. Hollywood produces a hundred pictures every year that would profit from his music. But Sierra Madre is not one of them. It is not amenable to the routine procedures he has established for himself in twenty years of composing. He appears not to have recognized that Sierra Madre did not fit into any of the usual categories, that it required a fresh approach, that it was a challenge to match in musical terms the special mood and emotional tone of Huston’s remarkably integrated workmanship. The picture needed musical local color, to be sure, but not the romantically Mexican kind that Steiner provided with his fandangos and snatches of amorous-nostalgic folk music.

Throughout the film the music is singularly inappropriate. No wonder that James Agee was moved to write, “One thing I do furiously resent is the intrusion of background music. There is relatively little of and some of it is better than average, but there shouldn’t be any, and I only hope and assume that Huston fought the use of it.” In this comment we observe the otherwise earnest and capable critic floundering when he discusses a department of film making that he only partly comprehends. To assume that Huston fought the use of music is indeed an assumption, and an assumption without grounds. For in Huston’s great wartime film, San Pietro, there was another score that was directly in opposition to the expressiveness of the film. From this one might assume that, sensitive as Huston is to the powers of other film crafts, he is to the same degree insensitive to the powers of music. One might also assume that the whole matter of music was not within his jurisdiction. But since the picture gives every evidence of his controlling hand in every other respect, it might justly be assumed that he could have had a proper score, or none at all, if he had known just what he wanted a score to accomplish, and if he had recognized that Steiner was just not his man. Agee’s comment exhibits the same kind of unawareness. Furiously to resent background music is sheer prejudice. A more knowing criticism would have resented only the wrong background music.

Hollywood Quarterly by Morton, Spring 1948, pp 316-318

Sierra Madre stands up to the closest study. The acting is impeccable, as is the pacing, the editing and the starkly dramatic photography of Ted McCord. Max Steiner’s score has been criticized for being more Spanish than Mexican and for being too loudly symphonic. The criticism is justified but assuming a fondness for Steiner it also has a tunefulness that helpfully lightens the darkly hued tale. And the main theme, the acutely accented melody that marks the spirit of the trek, is now so well associated with the picture that it is difficult to imagine Sierra Madre without it.

The Great Adventure Films, Thomas, 1980, p. 135

Research by Helen Arthurs

Notes compiled by Marcia Gillespie and Lloyd Gordon Ward

You may also like...

-

News

Frances Blau

Toronto Film Society | February 27, 2024On Monday, February 26th, 2024, Toronto Film Society lost longtime friend, supporter, and board member Frances Blau. Known for her sense of humour, her love of film, her generosity,...

-

Special Events

The Ladykillers (1955) at the Paradise Theatre

Toronto Film Society | March 9, 2024Toronto Film Society presents Targets (1968) at the Paradise Theatre on Sunday, April 7, 2024 at 2:30 p.m. Ealing Studios arguably reached its peak with this wonderfully hilarious and...

Programming

Virtual Saturday Night at the Movies

Toronto Film Society | April 11, 2024Toronto Film Society is back in the theatre! However, we’re still pleased to continue to bring you films straight to your home! Beginning Season 73 until now we have...

4-

Toronto Film Society | March 9, 2024

Toronto Film Society | March 9, 2024

-

Toronto Film Society | November 6, 2022

Toronto Film Society | November 6, 2022

-

Toronto Film Society | August 1, 2023

Toronto Film Society | August 1, 2023

Donate to Toronto Film Society – We’re now a Registered Charity!

-

Copyright © 2017 Toronto Film Society.

Leave a Reply