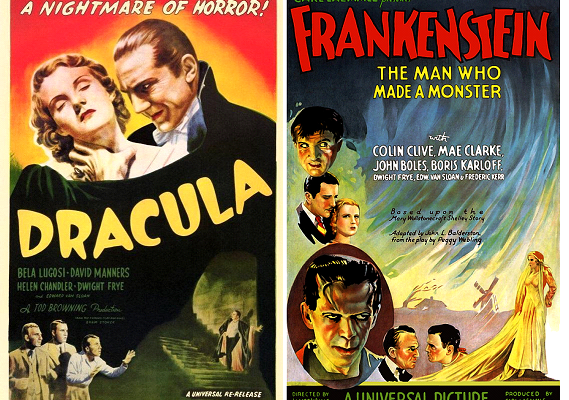

Dracula (1931) and Frankenstein (1931)

Toronto Film Society presented Dracula (1931) on Monday, October 24, 1983 in a double bill with Frankenstein (1931) as part of the Season 36 Monday Evening Film Buffs Series “B”, Programme 2.

Dracula (1931)

Production Company: Universal. Director: Tod Browning. Screenplay: Garrett For, fro the novel by Bram Stoker and the play by Hamilton Deane and John Balderston. Photography: Karl Freund. Editor: Milton Carruth. Sound: C. Roy Hunter.

Cast: Bela Lugosi (Count Dracula), Helen Chandler (Mina Seward), David Manners (John Harker), Dwight Frye (Renfield), Edward Van Sloan (Professor Van Helsing), Herbert Bunston (Doctor Seward), Frances Dade (Lucy Weston), Charles Gerrard (Martin), Joan Standing (Maid), Moon Carroll (Briggs), Josephine Velez (English Nurse), Michael Visaroff (Innkeeper).

INTERMISSION 15 MINUTES

Frankenstein (1931)

Production Company: Universal. Director: James Whale. Screenplay: Garrett Ford and Francis Edward Faragoh, based on the novel by Mary Wollstonecraft Shelley. Special Electrical Effects: Frank Graves, Kenneth Strickfadden, Raymond Lindsay. Technical Assistant: Dr. Cecil Reynolds. Photography: Arthur Edeson. Editor: Clarence Kolster. Sound: C. Roy Hunter.

Cast: Colin Clive (Henry Frankenstein), Mae Clarke (Elizabeth), John Boles (Victor Moritz), Boris Karloff (The Monster), Frederick Kerr (Baron Frankenstein), Edward Van Sloan (Doctor Waldman), Dwight Frye (Fritz), Lionel Belmore (Vogel, the Burgmaster), Marilyn Harris (Little Maria), Michael Mark (Ludwig, Peasant Father), Arletta Duncan, Pauline Moore (Bridesmaids), Francis Ford (Extra at Lecture/Wounded Villager on the Hill), Robert Livingston (Clive’s double).

It is interesting to speculate on the reactions of the original writers of “Dracula” and “Frankenstein” could they see what has happened to their respective creations. Both tales, according to their authors, began as nightmares. Both have certainly caused plenyt since. The two characters are the archetypes of fantastic horror film protagonists, the supernatural fiend and the man-made monster. From one or the other of them most of the other “things” (wolfmen, zombies) descended.

“I-am-Dra-cula. I bed you-welcome.” and “I never drink-eh-wine.” are undoubtedly the most famous lines in the history of horror films, spoken by one of the great actors in the genre: Bela Lugosi. If Dracula, the film, has retained any power to impress after over 50 years of repeated screenings, it is due in the main to Lugosi himself. It is useless to debate whether he was a good actor or not, Lugosi was Dracula: the actor’s identification with the part is complete. But Lugosi was not the original person considered for the role. Bram Stoker’s 1897 novel was dramatized for the stage by actor-manager Hamilton Deane and premiered in Derby, England in 1923, with Edmund Blake as the Count. Raymond Huntley played the lead in the London production, while Lugosi was chosen to portray the Count in the 1927 Broadway version. John Wray, who had been impressive in Universal’s All Quiet on the Western Front in 1930, as Himmelstoss, was the first actor announced for the Count. The list was then narrowed to Conrad Veidt, Paul Muni, Ian Keith, William Courtney and Bela Lugosi. It was rumored that Lon Chaney was considered for the role until his death in 1930.

In his novel, Bram Stoker went to considerable means and research to obtain authenticity for his story. He thoroughly investigated the legendary basis for the vampire. There was, it appears, a real-life Dracula–a military Governor in Walachia in the fifteenth century, a man of such cruelty that he was also known as ‘The Impaler’, and described as “wampyr”.

The first noteworthy film version was made in 1922, by F.W. Murnau, in Germany. It was unauthorized, and Stoker’s widow successfully sued the German production company. It is difficult, on re-viewing the Browning version nowadays, to see it through the eyes of the early 1930s. The dialogue is deadingly slow, and it is very stagey. Nevertheless, even when much of the film seems to be written off, there remains enough of a kind of macabre poetry to leave a stronger impression in the memory than many slicker examples since. The whole opening sequence is handled splendidly: the young agent arriving in the little mid-European village as the sun sets; the frightened inhabitants shutting themselves up as the night falls; the chattering old cab; the first sight of the gaunt coachman who takes over for the final part of the journey; the misty, ruined castle; the rats and dust; the Count and his three concubines grouped on the wide stairs–all atmospherically photographed by the great Karl Freund.

Dracula was an immediate success, and it instigated a number of ‘sequels’, none equaling the original success or production of the one starring Bela Lugosi.

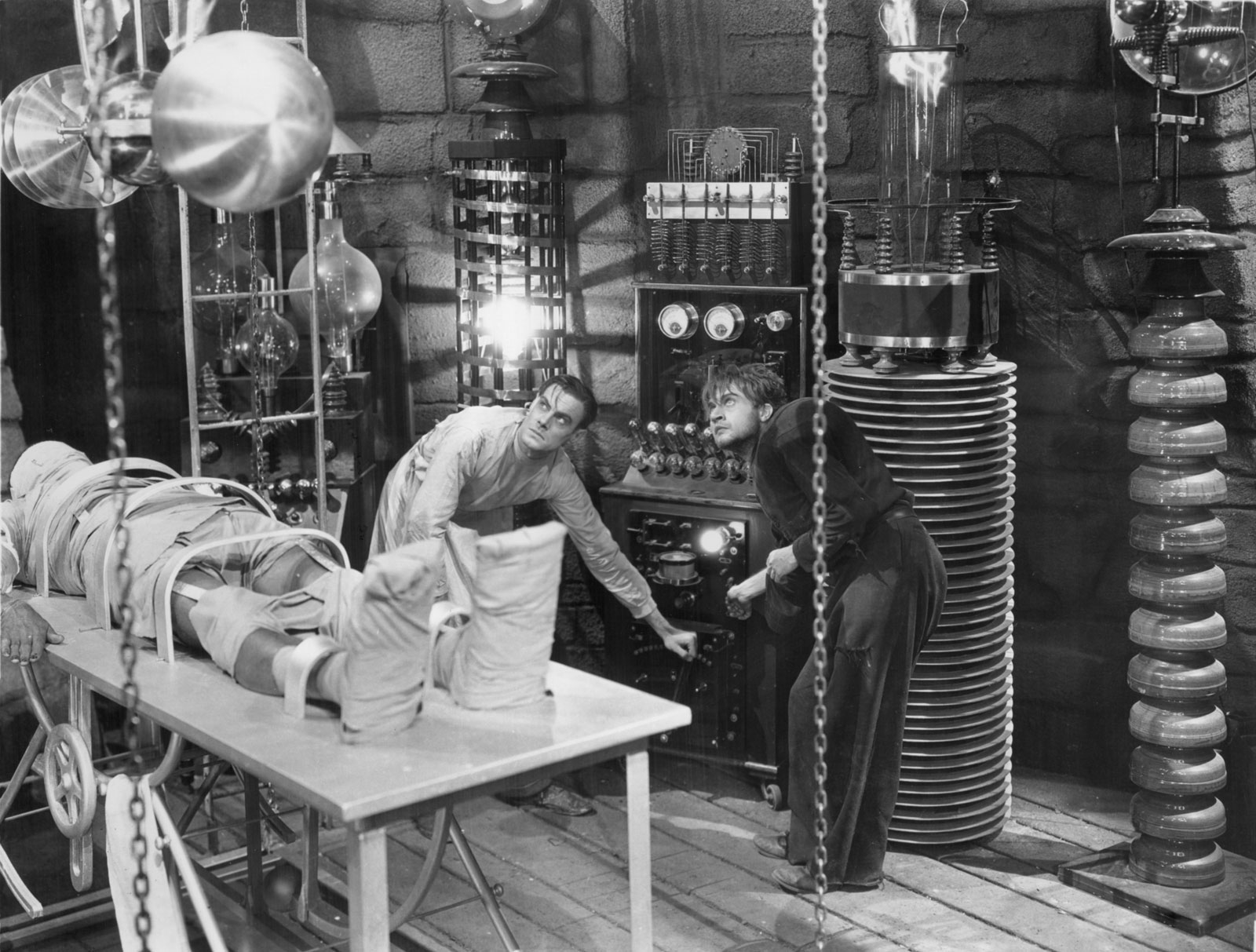

Even before Dracula was released, Universal contemplated a film version of Mary Shelley’s “Frankenstein”. Robert Florey, a French director, was initially assigned the task. He even made some camera tests with Lugosi made up as the monster. But Frankenstein was to emerge a quite different product from the early attempts. The major difference was that Lugosi refused the part, because the heavy make-up rendered him unrecognizable. In the light of the later productions, there is little gruesomeness in the film. There aren’t the typical gouged eyes, dismembered hands; nor is there any blood to be seen. Its terror is cold, chilling to the bone. The camera never lingers on the violent scenes, making the Monster’s first killing all the more effective, as a door is held open long enough to show the body of the Dwarf hanging on the wall like some terrible trophy. In these types of scenes James Whale’s unique direction is clearly evinced.

It was through Whale that Boris Karloff, who had been playing character roles, was tested and received the part. The actor then had to submit to four hour make-up sessions. Whale selected his friend Colin Clive to play Dr. Frankenstein, because Clive looked inimitably neurotic and high-strung. Clive has some good moments, and with his drawn, tormented face, he does manage to convey a feeling of the driven, possessed mania of the creator with a fine apocalyptic fervour.

But the film is remembered for Karloff’s role as the Monster. Jack Pierce’s make-up makes Karloff’s facial features practically naked under the built-up brow and heavy eyelids, allowing him a wide range of expression. He played the role three times, and brought a different interpretation to each. His successors in the role–Lon Chaney Jr., Glen Strange–never seemed to realize that there was considerably more to the Monster than the flattened skull, the electrodes, and the lead-weighted boots. The first sight of Karloff, despite its over-familiarity, still manages to shock. More remarkable is the sympathy he creates beneath the familiar trappings of horror.

Frankenstein went on to become one of the great monster movies of all time, and one of the great monster themes: the man-made monster. Frankenstein had a lot going for it at the time, but James Whale brought a quality that was, and still is, very rare–dignity. It was not just for the “normal” people, or the monster, but for the whole significance of his subject. Four years later, in 1935, Whale also directed the first of many sequels, The Bride of Frankenstein, which also starred Colin Clive and Boris Karloff. After that time many horror films appeared, but were very superficial. And as time went on, the horror film relied more on either gore or special effects. They did offer some compensating advantages over the earlier works, but could not by themselves replace imagination.

Notes by Fred Cohen

Leave a Reply