Carefree (1938)

Toronto Film Society presented Carefree (1938) on Monday, July 11, 1977 in a double bill with Show Boat as part of the Season 30 Summer Series, Programme 2.

Production Company: RKO-Radio. Producer: Pandro S. Berman. Director: Mark Sandrich. Screenplay: Allan Scott and Ernest Pagano. Story and Adaptation: Dudley Nichols and Hagar Wilde. Music and Lyrics: Irving Berlin. Musical Direction: Victor Baravalle. Ensembles Staged by: Hermes Pan. Photography: Robert de Grasse. Special Effects: Vernon L. Walker. Art Direction: Van Nest Polglase. Associate Art Direction: Carroll Clark. Set Decoration: Darrell Silvers. Miss Rogers’ Gowns: Howard Greer. Wardrobe: Edward Stevenson. Assistant Director: Argyle Nelson. Editor: William Hamilton. Recording: Hugh McDowell Jr. Songs: “Since They Turned ‘Loch Lomond’ Into Swing”, “I Used to be Color Blind”, “The Yam”, “Change Partners”, “The Night Is Filled With Music” (instrumental background).

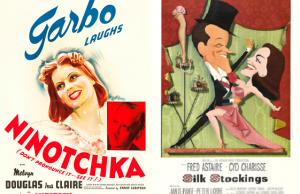

Cast: Fred Astaire (Dr. Tony Flagg), Ginger Rogers (Amanda Cooper), Ralph Bellamy (Stephen Arden), Luella Gear (Aunt Cora), Jack Carson (Connors), Clarence Kolb (Judge Joe Travers), Franklin Pangborn (Roland Hunter), Walter Kingsford (Dr. Powers), Kay Sutton (Miss Adams), Tom Tully (Policeman), Hattie McDaniel (Maid), Robert B. Mitchell and the St. Brendan’s Boys Choir.

Carefree is really more a comedy with music than a musical (only three tunes are sung with the other serving as a dance number and background music). It is also more Ginger Rogers’ film than Fred Astaire’s. Ginger is at her best in this one, having established herself as an actress in Stage Door and Having Wonderful Time. Maybe this gave her added self-confidence. Whatever the reason, her comedy timing and delivery dominate the film. While there are only four musical numbers, none of them is a failure and one at least is an incandescent achievement. “Since They Turned ‘Loch Lomond’ into Swing” is a Fred Astaire solo with no vocal. In this merry but fiendishly difficult solo he dances Scottish fashion over two golf balls crossed on the ground, then tees off some half-dozen balls in rhythm, pausing only for a fast shuffle between strokes. Each ball is straight as a shot. Plus, he plays a harmonica while dancing. This number is among Astaire’s own favourites. “I Used to Be Color Blind” is a short floating duet in a mock pastoral setting and a total surprise–not just because it’s slow motion but because so much of it takes place in the air. There are supported jumps for Rogers, a lift from which she’s lowered in a spiral and a long tandem leap across a brook. Astaire customarily avoids lifts. Carefree is full of them. Normally he partnered Rogers with one arm like steel around her waist, but in this film she hovers at his fingertips or is whirled about him in space. She takes the exposure marvelously, a point lavishly emphasized by the slow motion in “Color Blind”. More bewitching is “Change Partners”, which Astaire warbles with all his customary mellifluousness, prior to mesmerizing Ginger, via the usual hand-passes, into a dance-trance lissome even by their exalted standards. At the end they do one of their spiralling lifts with Rogers falling far backward in a tranquil arc, her arms wreathed over her head. The way she holds her poses in the air without “posing” is one of the loveliest things about Carefree.

The gem of the movie, and one of the sheerest incarnations of harmony and impromptu elan in dance which the cinema can boast, is, however, “The Yam”. Each fresh viewing of thisnumber yields a new richness: impossible to assimilate at one sitting all of Astaire’s dashing curves and thrusts and spurts of footwork. Above all, “The Yam” is the definitive illustration of the Rogers-Astaire dance secret. Again and again we discover in it a melodic, rhythmic and choreographic and physical contact between the couple–followed by a moment of pause, of telling contrast, where they stand poised and separated from one another, hands upraised (the music pausing too–on the song’s title-phrase). But then, the entire routine is a masterpiece. The informal ease with which, still holding his hand, Ginger bounces in and out of armchairs; the way in which they get the other guests to join in, cavorting in and out of rooms, and along winding terraces and passages; the wind-up back on the dance floor, where the number climaxes in a splendid series of flying lifts around the room. The sensational Yam Lift has a touch of the famous tabletop dance at the end of The Gay Divorcee, with Astaire lifting Rogers rapidly over a leg propped on ringside tables as they go round the carpet (a tour de force fully deserving the applause it receives). Finally, our happy surprise when we realize, after a long succession of dancing endurance, that–as Ginger and Fred begin to sing–the number is only half-way through! Such memories enrich the world.

Notes by Barry Chapman

Sources: The Musical Film by Douglas McVay (1967);

The Movie Musical by Lee Edward Stern (1974);

The Fred Astaire and Ginger Rogers Book by Arlene Croce (1972)

Leave a Reply