The Dancin’ Fool (1920)

Toronto Film Society presented The Dancin’ Fool (1920) on Monday, February 10, 1964 as part of the Season 16 Monday Evening Silent Film Series, Programme 4.

Programme No. 4

(Monday, February 10, 1964)

1911: G.M. Anderson in Shootin’ Mad

1915: Lillian Gish in Enoch Arden (excerpt only) with Wallace Reid

Intermission

1920: Wallace Reid in The Dancin’ Fool with Bebe Daniels

* * *

Shootin’ Mad

Produced, directed and acted by G.M. (“Broncho Billy”) Anderson

for the Essanay Film Manufacturing Co. “c1911”

Leading lady: Marguerite Clayton

(In 2 reels)

(Some of our members will recall that the chase sequence from this film was shown in the TFS Main Series a year or two back, as part of the program devoted to The Western).

Max Aronson was born in Little Rock, Arkansas, in 1882. At the age of 18 he changed his name to Gilbert M.Anderson to embark on a career as a vaudeville actor; but at the age of 18 we find him reduced to acting in moving pictures,–specifically at the Edison studios in New York, playing several bit parts in The Great Train Robbery (1903). By 1905 he was directing films for Vitagraph and subsequently for Selig. Then in 1907 he and George K. Spoor formed a company of their own which they called “Essanay” (“S & A” – get it?), and opened studios in Chicago where Anderson began producing comedies. The following year he opened a branch studio in Niles, California, (one of t he first movie companies to migrate to the West Coast), and the first film he made there was an adaptation of a Peter B. Kyne short story, Brochcho Billy and the Baby. For want of an actor to play the title role (California in those pre-Hollywood days was not yet crawling with unemployed actors), Anderson took om the chore himself, though he could barely climb onto a horse, let alone ride one. He eventually had to learn, however, for Broncho Billy and the Baby proved such a hit that it launched a whole series of films (one-reelers at first, but later two-reelers) built around the character of Broncho Billy, produced and released at the rate of one a week (like a modern television series–plus ça change!) They were not the first Westerns,–there had been tentative gropings even before The Great Train Robbery, and the latter had spawned innumerable imitations; but they were the first to be built around a central character (which even The Great Train Robbery lacked), and they launched “Broncho Billy” Anderson willy-nilly as the first Cowboy star in movie history.

It is well that Anderson had novelty on his side, for a less personable hero can hardly be imagined. It is true that beefiness was a characteristic of many of the male stars of the pre-1914 era (William Farnum, Francis X. Bushman et al.) so that this was not the handicap then that it is for us; but facially he had neither good looks nor a compensating personality,–in short, he had little of the healthy-animal appeal that even third-rate cowboy stars usually possess. But the fact remains that he was enormously popular, and for seven years the fans flocked to the movie houses every week to see the latest Broncho Billy film.

The secret of his popularity, of course, lay in the films themselves,–for what Anderson lacked as an actor he made up for as writer and director. And what the films lacked in authenticity (in contrast to those of Wm. S. Hart) they made up for in vigor and action and lively entertainment; and if Shootin’ Mad is a representative sample, they still stand up to this day (providing you can overlook Anderson’s shortcomings as a personality). Their popularity established the Western as a genre, quickly taken up by other companies not only in the U.S. but even in Europe (Denmark in particular producing quite a number of cowboy movies around this time),–and they laid down most of the rules that classic Westerns have obeyed ever since.

Anderson resisted the general trend to feature films until about 1915, when he finally capitulated only to find himself overshadowed by Tom Mix and William S. Hart, and he soon withdrew. In the 1920’s he returned to making two-reel comedies, including several successful ones starring Stan Laurel, till he had a run-in with Louis B. Mayer in 1923 and retired from films forever. As of this writing, Anderson is still alive, in his eighties. In 1958 he appeared on an NBC-TV 90-minute documentary about Westerns, talking about the pioneer days of making cowboy movies.

Marguerite Clayton, Anderson’s leading lady in this and several other of his films, continued to be active throughout most of the ‘teens. Whether or not she was related to her more popular contemporary, Ethel Clayton, I don’t know.

Enoch Arden (excerpt only)

Released by the Mutual Film Corporation, 1915

Based on the poem by Alfred Tennyson

Directed by Christy Cabanné

Supervised by D.W. Griffith

Players: Lillian Gish, Wallace Reid, Alfred Paget, Mildred Harris

(Reissued in 1922 as The Fatal Marriage)

An earlier version by Griffith of Tennyson’s celebrated poem made motion picture history in 1911 by being the first successful two-reel film ever produced,–in America, at any rate (see notes for Programme No. 1). Four years later the five-reel feature film had been firmly established as the norm, and Griffith had another go at the story, though this time it was directed by one of his subordinates.

More than this we cannot tell you, and at this writing we haven’t seen the film yet. For notes on Lillian Gish, see next month’s programme (Way Down East); and for Wallace Reid, see below. And in case you’re interested, Mildred Harris was later to become Charlie Chaplin’s first wife.

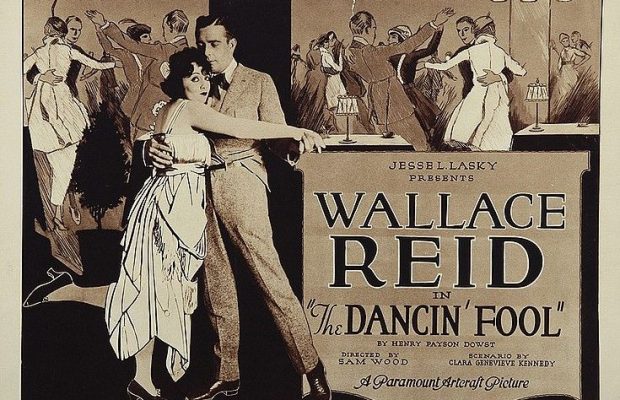

The Dancin’ Fool

Produced by Famous Players-Lasky; released May 1920

Directed by Sam Wood

Story by Henry Payson Dowst

Continuity by Clara G. Kennedy

Players: Wallace Reid, Bebe Daniels, Raymond Hatton, Willis Markes, Tully Marshall, Lillian Leighton

For a contemporary impression of this film, we quote in its entirety the review of it published in Photoplay Magazine for August, 1920, (but be warned that it gives away the plot!):

The Dancin’ Fool is another of the month’s pictures in which the virtues of a human story overcome the handicaps of a feather-weight and fantastic comedy plot. It really doesn’t matter how trivial a story may be, if it is sound at heart. The world, it happens, is full of “dancin’ fools”, bright lads who just can’t make their feet behave and find it irksome to buckle down to work with the lure of jazz ringing in their ears. It isn’t as easy to accept the wise Wallace Reid as an unsophisticated country youth as it is Charles Ray, but he has enough of the same engaging quality of youthful exuberance to endear him to a large public, and he carries the hero of this story through a series of city adventures with uncommon skill. His regular job is that of a $6-a-week clerk in his old-fashioned uncle’s jug business, but he happens to meet Bebe Daniels, who is dancing at a cabaret, and after she has taught him the newest steps, he becomes her partner. Of course uncle discovers him foolin’ away his evenin’s, and fires him for the fourteenth and last time. But Wallace refuses to be fired and ends by saving his uncle from selling out his business to a couple of Tully Marshall villains just as it is about to boom. Then he marries Bebe, which is bound to be a satisfying ending to anyone who has taken note of the physical attractions of this young lade. It also happens that Miss Daniels is something more than beautiful. She has that “certain subtle something” that differentiates the real from the merely personable heroine, and her announced elevation to stardom is easy to endorse. Raymond Hatton is excellent as the Uncle Enoch of the jug business, and Willis Markes, Tully Marshall, and Lillian Leighton help considerably.

Anyone who has seen The Birth of a Nation will undoubtedly recall the brief scene in which a young blacksmith, looking for the renegade negro who caused the young girl’s death, is himself treacherously shot. When The Birth of a Nation had its Los Angeles premiere in February 1915, Jesse Lasky and Cecil DeMille went to see it, and in addition to their genuine admiration for the film, they were also moved by a “larcenous inspiration”. But let Mr. Lasky tell his own story:

A young man who played a bit part as a blacksmith had a perfect physique, large, expressive eyes, and flawless features. He was about six feet tall and weighed in the neighborhood of 180 pounds. Seeing him was just like finding a 180-pound diamond, for within a year we would be reaping gratifying profits from eight pictures featuring his brawn and irresistible appeal, and the tonnage of his fan mail would be making our distaff stars jealous. We signed him and kept him under contract to the day of his tragic death eight years later at the height of unprecedented popularity.

Son of the playwright Hal Reid, Wallace Reid had inherited his father’s gift for storytelling, had a keen sense of humor, a good singing voice, played the saxophone and piano, and was altogether the most magnetic, charming, personable, handsome young man I’ve ever met. And the most co-operative.

The Lasky Feature Play Corporation (soon to be amalgamated with Adolph Zukor’s Famous Players Film Co.) had been in business only about a year at the time The Birth of a Nation had its premiere. Had Lasky been following the older companies’ output a little more closely, both before and after going into the film business himself, he might have discovered Wallace Reid long before he did.

Wallace Reid was born in St. Louis, Missouri, on April 15, 1892. Both of his parents were theatre people, his father, Hal Reid, being an actor and a director as well as a successful playwright. So successful, in fact, that it wasn’t long before the Reids were centered in New York, with an apartment in Manhattan and a country estate at Highlands, New Jersey. In short, the Reids were “well off”, and Wallace was an only child, and benefited from a loving family, freedom from want, and a good education.

Although he toured briefly in one of this father’s plays, Wallace seems to have done little acting before he began doing film work at the Vitagraph studios in New York in 1911, where his father also began working both as actor and as writer. (It has been said that Hal Reid brought his son to the studio as a would-be cameraman, but that the producers soon saw he would be of more value to them in front of the camera. It has also been reported that, being a competent violinist, Wallace also used to double as studio musician when mood music was required by the actors.) Among other films, Wallace appeared in Vitagraph’s series based on Cooper’s Leatherstocking tales,–undoubtedly to his great delight, for apparently Cooper had been his boyhood’s favorite author.

Presently both father (as scenario writer) and son were working for Universal, and were transferred to the California studios; and thereafter Wallace worked for various companies, including Mutual, before Lasky signed him up in 1915. (Enoch Arden must have been one of the last films he made before signing with Lasky).

The Lasky contract did not make him a “star” immediately, but he had choice leading roles in outstanding pictures–he appeared opposite most of Lasky’s important stars, including Geraldine Farrar in her much-publicized entry into films in Carmen (1915) and in several of her subsequent films, directed by DeMille,–and it didn’t take the fans long to respond. As Joe Franklin puts it, “Reid was extremely fortunate in that he possessed acting ability, youth, good looks and a fine physique–four assets that were rarely found in the same person, especially in those days when the best acting talent was usually centered in more mature players who had been brought to the movies from the stage”. By the end of 1916 Wallace Reid stood tenth in the popularity poll conducted by Motion Picture Magazine (see the notes for our Programme No. 1, October 28, 1963). By the end of 1920 he was rated as the top male star–ahead of Charles, Ray, Thomas Meighan, Eugene O’Brien, Douglas Fairbanks and William S. Hart (in that order). (The top women, in case you’re curious, were Norma Talmadge, Constance Talmadge, Mary Pickford, Anita Stewart, Dorothy Gish, Clara Kimball Young and Gloria Swanson).

He was officially elevated to stardom in 1918, and though he occasionally continued to appear in some of Cecil DeMille’s specials, such as The Affairs of Anatol (1921), and opposit Elsie Ferguson in a screen adaptation of Peter Ibbetson (Forever, 1921), most of his films were just light-weight, routinely-made pictures turned out to meet public demand for Wallace Reid in anything. (A few sample titles: “Believe Me, Xantippe, Less than Kin, The Roaring Road, The Lottery Man, What’s Your Hurry, Double Speed, Sick Abed, The Dancin’ Fool, Excuse My Dust, Clarence, Rent Free, The Dictator). If they were not important as films, the best of them were at least unpretentious and agreeable entertainment, comfortably suited to the tastes of the day, (and as such, far more important to social historians than the more universal masterworks).

But now let us return to Jesse Lasky for the rest of the story:

Wallace Reid was the easiest actor to cast and work with in the whole of my experience. He had a terrific vogue in automobile-racing pictures–the audiences couldn’t get enough of him behind a steering wheel. We virtually turned these road-racing items out on an assembly line and every one was a money-maker. But that didn’t type Wally. He was believable in almost any role we gave him. However, he wasn’t believable as a heavyweight fighter in The World’s Champion, taken from a Broadway play. He was rapidly losing weight and couldn’t stand on his feet for more than a short time. He made a valiant struggle to get through his scenes, but it was obvious that something was wrong. Then Zukor wrote me that the whole country was teeming with a rumor that Wallace Reid was taking dope, and that if it was true we were sitting on a powder keg. Will Hays called me long-distance and told me I would have to do something about it.

I sent for Reid. As fond as I was of him, it was very difficult for me to say what I had to. I told him about the rumor, which had now fanned into a whirlwind of gossip, and that as head of production I was being held responsible for his actions.

“It isn’t true!” he said, looking me squarely in the eye. “And don’t you believe it!”

Perhaps it wasn’t true at that moment. His loss of weight and unnatural fatigue during the shooting of the picture were symptoms that might have accompanied a desperate attempt to “kick” the narcotic habit.

“I want to believe you, Wally”, I told him, “But the only way that rumors can be stopped is by absolute proof that they’re false. Would you mind if I got a doctor to examine you?”

“Why should I” he said. “Go as far as you like”.

Our studio manager, Charles Eyton, borrowed a young railroad physician from the Southern Pacific. I told the doctor what we suspected and that we wanted him to live with Wallace for a time, never letting him out of his sight, and then bring us the facts, whatever they were. He was agreeable. I called in Wally again and told him our plan to spike the rumors, if there was nothing to them, by assigning the doctor to keep him under constant observation. No one need know that he wasn’t just a pal, accompanying him wherever he went.

Wally assented readily without a shadow of annoyance. He was the perfect image of a man with nothing to hide. The doctor stayed with him two weeks, then reported back to me. “To the best of my knowledge, Mr. Lasky,” he said, “Wallace Reid is not using narcotics. I’ve eaten my meals with him, slept in the same room with him, followed him to the bathroom, played golf with him, searched his belongings. He’s co-operated wonderfully. I don’t know anyone else I could live with like Siamese twins for two weeks without wanting to murder, but he is unquestionably the nicest chap I’ve ever known”.

I breathed a premature sigh of relief and notified Hays and Zukor that there was nothing to worry about–the doctor had given Wally a clean bill of health.

A few weeks later Reid was taken to the Banksia Place Sanitorium, his health so undermined that he never recovered. Will Hays and I visited him there just before he died in 1923, only thirty years old.

There was no question of the doctor’s integrity. Either he fell under the spell of the magnetic personality that exerted its effect on the whole country, and unwittingly slackened his surveillance with the conviction that it wasn’t necessary, or else Wally was fighting a battle alone to salvage his reputation at any cost, and actually kicked his habit by his own will power–too late. It was established later that he did not contract the addiction as a thrill seeker. It started from being given narcotic injections to relieve distracting headaches that resulted from a head injury in a train wreck.

(from I Blow My Own Horn, pp 157-8)

Reid died on January 18, 1923. When he went into the sanitorium, just before Christmas, his family openly revealed his plight, hoping that publicizing it might serve as a timely warning to prospective victims of the drug habit; and after his death his wife, a former actress named Dorothy Davenport (they were married October 13, 1913, and had one son) made a successful film called Human Wreckage, with the avowed purpose of alerting the public to the drug evils.

Although his death was not due directly to the drugs themselves but to his valiant struggle to break the habit, the public that had idolized Wallace Reid as the epitome of clean-cut American youth was shocked by the revelation that he had been a “dope fiend”. Perhaps that is one reason why, though like Valentino he died at the height of his popularity (at almost the same age), he never became a legend. Or could it be that Valentino vogue introduced a new, sexy type of matinee idol that rendered the more “wholesome” Wallace Reids and Charles Rays obsolete? Whatever the reason, the very name of the most popular male star of 1921 is unfamiliar in 1964 except to the old-timers who remember him.

Of the numerous films Wallace Reid made as a star for Famous Players-Lasky (Paramount), only two are offered by the Film Library of the Museum of Modern Art: The Dancin’ Fool and Excuse My Dust (both 1920). The latter is said to be the better of the two, and as an auto-racing picture it would be a better representative of his more popular films, as well as showing him in a more typical role (to judge from Photoplay‘s review of the other film). But we selected The Dancin’ Fool because of the presence in the cast of Bebe Daniels, on her way to becoming a popular screen star in her own right. (Maybe we’ll show Excuse My Dust another season, if you like).

BEBE DANIELS was born in Dallas, Texas, on January 14, 1901. She made her stage debut in that city at the age of four as the Duke of York in Richard III, and by the following year was appearing in productions for Oliver Morosco and David Belasco. Thus she had quite a busy career as a child actress both before and after entering films. During the ‘teens she appeared mostly in comedy shorts (opposite Harold Lloyd in his early Lonesome Luke series, among others), till Cecil DeMille decided she was worth better things, and, starting with a bit in the Babylonian sequence of Male and Female, began giving her increasingly important roles in many of his films. She played opposite Wallace Reid in several films, and opposite other male stars; and was raised to stardom in 1922 (if David Blum is right; in 1920 if Photoplay Magazine wasn’t premature–see the quoted review). She not only held her own when talkies came in but revealed a hitherto unsuspected talent for singing, and appeared in a number of musicals, including 42nd Street and the screen version of Rio Rita.

In 1935 she returned to the stage with her husband Ben Lyon (another popular star of Silent days and early talkies) in something called Hollywood Holiday; then went to England to appear in several British films (1936-38) and o the stage in variety and musicals; and she and Ben Lyon have been prominent in British show business ever since, chiefly in radio and television. Their steadfast refusal to leave Britain during the War greatly endeared them to the British public. After the War, Bebe was back in the States for awhile where among other things she directed a film for Hal Roach: The Fabulous Joe (1948). She returned to London in 1949. She is part-author of the long-running series, Life with the Lyons. Recent reports indicate that she is seriously ill.

Raymond Hatton, in films since 1916 or before, was co-starred in the later 1920’s with Wallace Beery, as a comedy team in a successful series of films.

Notes by Fraser Macdonald

Next programme: Monday March 16 – Way Down East with Lillian Gish and Richard Barthelmess, directed by D.W. Griffith. Also, as a curiosity, an early film showing Griffith as an actor: At the Crossroads of Life (1908).

Leave a Reply