Gideon of Scotland Yard (1959)

Toronto Film Society presented Gideon of Scotland Yard on Monday, September 25, 1978 in a double bill with Shane as part of the Season 31 Monday Evening Film Buff Series, Programme 2.

Production Company: Columbia (Columbia British Productions). Producer: Michael Killanin. Director: John Ford. Associate Producer: Wingate Smith. Screenplay: T.E.B. Clarke, from the novel, “Gideon’s Day”, by J.J. Marric (Pseudonym for John Creasey). Photography: (in colour, but generally released in black and white) Frederick A. Young. Art Direction: Ken Adam. Music: Douglas Gamley. Editor: Raymond Poulton. Assistant Director: Tom Pevsner.

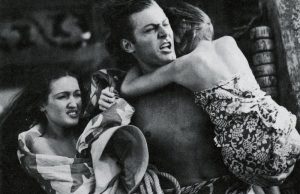

Cast: Jack Hawkins (Inspector George Gideon), Dianne Foster (Joanna Delafield), Anna Massey (Sally Gideon), Cyril Cusack (Herbert ‘Birdie’ Sparrow), Andrew Ray (P.C. Simon Farnaby-Green), Anna Lee (Mrs. Kate Gideon), James Hayter (Mason), Ronald Howard (Paul Delafield), Howard Marion-Crawford (Chief of Scotland Yard), Laurence Naismith (Arthur Sayer), Derek Bond (Det. Sgt Eric Kirby), Griselda Harvey (Mrs. Kirby), Frank Lawton (Det. Sgt Liggott), John Loder (Ponsford, ‘The Duke’), Marjorie Rhodes (Mrs. Saparelli), Michael Shepley (Sir Rupert Bellamy), Michael Trubshawe (Sgt Golightly), Jack Watling (Rev. Julian Small), Hermione Bell (Dolly Saparelli), Donal Donnelly (Feeney), Billie Whitelaw (Christine), Malcolm Ranson (Ronnie Gideon) Mavis Ranson (Jane Gideon), Francis Crowdy (Fitzhubert), David Aylmer (Manners), Brian Smith (White-Douglas), Barry Keegan (Riley, chauffeur), Maureen Potter (Ethel Sparrow), Henry Longhurst (Rev. Mr. Courtney), Charles Maunsell (Walker), Stuart Saunders (Chancery Lane policeman), Dervis Ward (Simo), Joan Ingram (Lady Bellamy), Nigel Fitzgerald (Insp. Cameron), Robert Raglan (Dawson), John Warwick (Insp. Gillick), John Le Mesurier (Prosecuting attorney), Peter Godsell (Jimmy), Robert Bruce (Defending attorney), Alan Rolfe (C.I.D. man at hospital), Derek Prentice (1st employer), Alastair Hunter (2nd employer), Helen Goss (woman employer), Susan Richmond (Aunt May), Raymond Rollett (Uncle Dick), Lucy Griffiths (Cashier), Mary Donevan (Usherette), O’Donovan Shiell, Bart Allison, Michael O’Duffy (Policemen), Diana Chesney (Barmaid), David Storm (Court Clerk), Gordon Harris (C.I.D. man). Filmed in London.

What was America’s finest director, the maker of the greatest Westerns (The Searchers, Fort Apache, Wagonmaster, My Darling Clementine, She Wore a Yellow Ribbon and  Stagecoach) and dramas (How Green Was My Valley, The Grapes of Wrath, The Sun Shines Bright, Young Mr. Lincoln, The Quiet Man and They Were Expendable) in film history, doing going to England to film a minor comedy adventure about Scotland Yard? Ford himself simply stated: “I wanted to get away for a while, so I said I’d like to do a Scotland Yard thing and we went over and did it.”

Stagecoach) and dramas (How Green Was My Valley, The Grapes of Wrath, The Sun Shines Bright, Young Mr. Lincoln, The Quiet Man and They Were Expendable) in film history, doing going to England to film a minor comedy adventure about Scotland Yard? Ford himself simply stated: “I wanted to get away for a while, so I said I’d like to do a Scotland Yard thing and we went over and did it.”

Andrew Sarris observes: “…but more often Ford tended to trot out the old stiff-upper-lip clichés about the English with an air of directorial absent-mindedness, never looking beneath the stereo-type for the subterranean feelings of individuals. With the English, Ford’s mystical poetry turns into mechanical prose. He observes, but he does not intervene.

It is this passive, distanced quality, which makes Gideon of Scotland Yard one of Ford’s most peculiar projects I his late period. From the opening shot of Jack Hawkins’ nightmarish confrontation with a slowly dollying camera (an effect which is more hallucinatory in colou prints of the film than in the black-and-white version in general release) to the closing shot of Hawkins’ bemused mini–triumph over an overly scrupulous son-in-law to be, Ford has packed more incident into one feature film than in to any five of his other films. He seems to be mocking not only the English but  also the noveau-Scotland Yard genre of which “Gideon’s Day” by J.J. Marric was a typical example. Whereas Ford’s Irish tend to be indolent and dilatory, his English are hustling and bustling in their bumbling manner, with periodic pauses for their tepid tea and beastly buns, and then back to the treadmill of their eccentrically formalized routines. Ford plays up the comedy and the satire at the expense of the more sombre Simenonism of the genre itself, but his gallery of English and Irish actors somehow become extraordinarily vivid on the fly, as it were, as if they could have taken off to loftier realms of mood and insight if Ford had responded to them with a fraction of the feeling he devotes to Denis O’Dea’s police sergeant and Eileen Crowe’s bed-warming and conscience-stirring wife in the third episode of The Rising of the Moon. With Ford it is truly a question of accepting an inescapable connection between the level of his artistic expression and the intensity of his emotional commitment;…”

also the noveau-Scotland Yard genre of which “Gideon’s Day” by J.J. Marric was a typical example. Whereas Ford’s Irish tend to be indolent and dilatory, his English are hustling and bustling in their bumbling manner, with periodic pauses for their tepid tea and beastly buns, and then back to the treadmill of their eccentrically formalized routines. Ford plays up the comedy and the satire at the expense of the more sombre Simenonism of the genre itself, but his gallery of English and Irish actors somehow become extraordinarily vivid on the fly, as it were, as if they could have taken off to loftier realms of mood and insight if Ford had responded to them with a fraction of the feeling he devotes to Denis O’Dea’s police sergeant and Eileen Crowe’s bed-warming and conscience-stirring wife in the third episode of The Rising of the Moon. With Ford it is truly a question of accepting an inescapable connection between the level of his artistic expression and the intensity of his emotional commitment;…”

And Jack Hawkins would write: “I think one thing delighted him above all others in making Gideon’s Day; a guided tour of Scotland Yard was arranged for us. Here the thing that really caught his fancy was that every spare level surface seemed to have a cup of tea parked on it. He mentioned this to the senior police officer who was showing us around, and later he was  asked if tea-cups could be kept out of the film. Obviously, it was thought that they did not give a very good impression of what is possibly the best-known police headquarters in the world.

asked if tea-cups could be kept out of the film. Obviously, it was thought that they did not give a very good impression of what is possibly the best-known police headquarters in the world.

Solemnly, John said that he quite understood, but his Irish sense of mischief got the better of him, for when the film appeared, every desk, shelf and filing-cabinet in Scotland Yard carried its ubiquitous cup and saucer!”

The answer, then, is to view this film in the same spirit it was made–a spirit of interested observation and, above all, fun.

References: John Ford by Peter Bogdanovich, U of Cal. Press, 1968; Anything for a Quiet Life by Jack Hawkins, Elm Tree, 1973; The John Ford Movie Mystery by Andrew Sarris, Secker & Warburg, London, 1976

Notes compiled by Jaan Salk

Leave a Reply