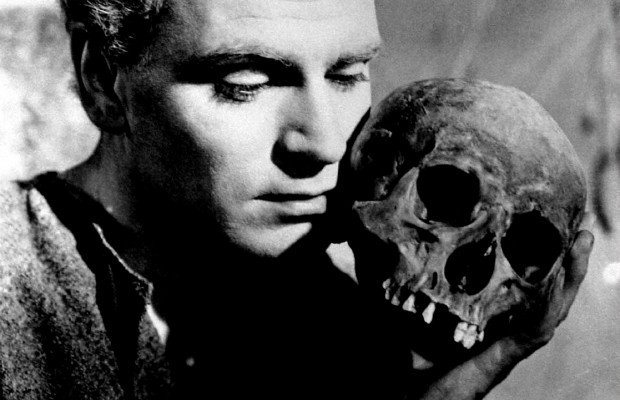

Hamlet (1948)

Toronto Film Society presented Hamlet (1948) on Monday, March 9, 1981 in a double bill with Intermezzo as part of the Season 33 Monday Evening Film Buff Series, Programme 7.

Hamlet, or part of it, had been brought to the screen at least ten times before Olivier’s famous film. The first version, in 1900, recorded three or four minutes of performance by Sarah Bernhardt as the Prince. There were two French versions (George Melies in 1907; another in 1910), one Italian (1908), one British (1910), one Danish (1913, and set in Kronberg Castle, the original of Elsinore), one American (Vitagraph, 1914), and one remarkable German Art Film (1920), based less upon Hamlet than upon Saxo Grammaticus’ source, with the Swedish actress Asta Nielsen as Hamlet. In addition to such fuller treatments, there were brief excerpts aimed at enhancing the actor rather than the play: not only the Divine Sarah’s 1900 performance, but Forbes-Robertson’s in 1913, Barrymore’s in 1933.

Of the three Shakespearian films directed by Olivier, this one has seemed in recent years to be the least satisfactory. In Henry V (1944), he had taken the camera far beyond the wooden O of the Elizabethan playhouse, and by the time of Richard III (1955) he seemed less bemused by the techniques of the cinema. It is these techniques that detract from the full impact of the play itself in the filmed Hamlet. The film overuses travelling shots, tracking constantly, panning, circling around the actors and the sets (The fact that the sets themselves are highly artificial in a way well-suited to the stage makes the film a further theatre/cinema hybrid when subjected to such camera work). The final segment of the film, however, is both cinematically and theatrically brilliant, as Hamlet is borne “like a soldier to the stage,” high above the battlements. The sequence of shots surveys the whole castle, visually reminiscing over portions of it associated with earlier scenes, and bringing the parts of the play dramatically and visually to final coherence (Suggestively, this segment, Olivier claimed, was what first appeared in his mind, and was the genesis of the film).

Contemporary reviews criticized the excessive Freudianism of the film (Hamlet appeared much less concerned with the murder of his father than with the frailty of his mother), and noted the apparently minimal age difference between Olivier and Eileen Herlie. More recent opinion has condemned the film’s reductive approach to the play: it begins with the striking statement, “This is the tragedy of a man who could not make up his mind” (The way the Oedipus Complex may be defined as an inability to make up one’s mind).

Olivier himself thought his style of acting better suited to such roles as Henry V, and, preferring to direct, was at first unwilling to play the Prince. While one might have wished for a Gielgud or a Scofield (later) under Olivier’s direction, the film certainly revealed Olivier to be, as Roger Manvell (Shakespeare and the Film) remarked, “a theatrical showman as well as agreat artist”; and there is no gainsaying that it brought the greatest of all plays to a wider audience than it had ever commanded.

Hamlet opened in London on May 6, 1948, with the King and most of the Royal Family present (they actually arrived ten minutes late); the American premiere was three months later in Boston. The film won four Academy awards, and was the first foreign film ever named Best Picture of the Year.

Notes by Barrie Hayne

Leave a Reply