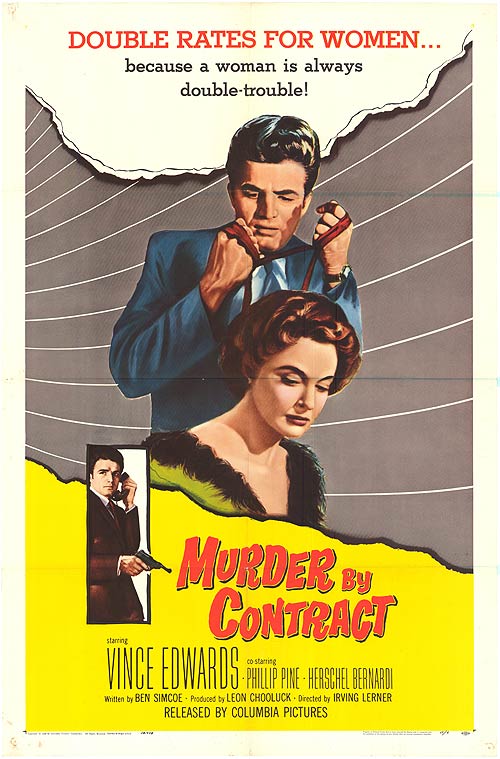

Murder by Contract (1958)

Toronto Film Society presented Murder by Contract (1958) on Monday, August 13, 2018 in a double bill with Midnight Lace as part of the Season 71 Summer Series, Programme 5.

Toronto Film Society presented Murder by Contract (1958) on Sunday, January 30, 1983 in a double bill with The Last Picture Show as part of the Season 35 Sunday Afternoon Film Buffs Series “A”, Programme 6.

Production Company: Orbit Productions. Producer: Leon Chooluck. Director: Irving Lerner. Script: Ben Simcoe. Cinematography: Lucien Ballard. Editor: Carlo Lodato. Art Director: Jack Poplin. Sound: Jack Soloman. Music: Perry Botkin. Release Date: December, 1958.

Cast: Vince Edwards (Claude), Phillip Pine (Marc), Herschel Bernardi (George), Caprice Toriel (Billie Williams), Cathy Browne (Mary, Blonde Secretary and Party Girl), Michael Granger (Mr. Moon), Frances Osborne (Miss Wiley, Ex-maid).

Director Irving Lerner’s credits do not follow a linear path; he began his career in the New York wing of the Workers Film and Photo League, a collective that made radical leftist propaganda. He eventually formed a separate production company, Nykino, with avant garde photographer Ralph Steiner and Leo Hurwitz, best known for directing the Paul Robeson-narrated trade union documentary Native Land (1942). Hurwitz was eventually blacklisted for his political leanings.

Lerner did not face the same career-damning fate, perhaps because of his increasing preference of aesthetic beauty over politics. This less polarizing tendency served well in the next phase of his career during making films for the Office of War Information during the war years. Personal projects followed, including a lyrical ode to the benefits of reducing fat and increasing muscle in the short documentary Muscle Beach (1951). Lerner never scored a big hit or landed a studio contract, instead his resume included numerous jobs: cinematographer, editor, technical advisor, and even production associate on the infamous 3D indie Robot Monster (1953).

Murder by Contract, one of a handful of features that Lerner directed, is often considered a late-period film noir but the film owes very little to the silky sheen of the post-war style. It’s probably more appropriate to link it to the nascent French New Wave (which is traditionally noted as being born in 1958 with Claude Chabrol’s La Beau Serge)—the characters speak in cool and clipped style, the tone is decidedly nihilistic and modern, and the stark photography eschews romanticism. Martin Scorsese is a big admirer and it’s easy to connect the dots between Vince Edwards’ character and Travis Bickle in Taxi Driver. This debt would be repaid when Lerner was hired on as supervising editor on Scorsese’s New York, New York (1977). The film was, in fact, dedicated to him as Lerner passed away shortly before it was released.

The most outstanding element of this unusual film is the guitar score by Perry Botkin. Botkin was a veteran big band guitarist who worked with likes of Paul Whiteman, Eddie Cantor, Glenn Miller, Spike Jones, and Benny Goodman. Most notably he served as Bing Crosby’s musical director for nearly two decades. Next time you catch an episode of “The Beverly Hillbillies”, pay attention to the incidental music—that’s Botkin’s sparkling string work. His score for Murder by Contract is the driving force much like the zither of The Third Man, the minimalistic score worms its way throughout the picture at times overwhelming the image.

Introduction by Adam Williams

Murder by Contract is a film-noir made on a modest budget and did not attract a large audience upon its release. However, it is now considered to be a minor classic and was released on DVD in 2009 in the boxed set, “Columbia Pictures Film Noir Classics, Vol. 1.”

Director Martin Scorsese cites Murder by Contract as the film that influenced his approach to filmmaking the most. He compares the style and storytelling of the film to the work of Robert Bresson and Jean-Luc Goddard. The musical score of the film was all guitar, composed by jazz guitarist and composer Perry Botkin. The 1958 review of the film in the entertainment magazine Variety praised the score for its “fine atmospheric backing.” The Time Out Film Guide gives the film high praise as being ahead of its time and says, “Lerner and his superb cameraman, Lucien Ballard, make the most of a shoestring budget to produce a taut, spare, amoral film; it doesn’t look restricted, it looks restrained.”

The film’s cameraman, Lucien Ballard, A.S.C., had an inauspicious start to his career. He was born on May 6, 1908 in Miami, Oklahoma as Lucien Keith Ballard. He attended the University of Oklahoma and the University of Pennsylvania. By his own admission, he had been kicked out of three or four universities and had a number of different jobs before ending up in Los Angeles. He had a girlfriend who was a script girl at Paramount Studios in 1929. Because a fire had destroyed a sound stage, production often worked at night. Ballard would visit his girlfriend while scenes were being shot and it wasn’t long before he was asked to help out some of the cameramen moving cameras and equipment. Before long, he got a full-time job at Paramount. His first job for Paramount was working on the Clara Bow film Dangerous Curves (1929). He was invited to Bow’s home for the cast party at the end of filming. He told Leonard Maltin in an interview: “Clara Bow invited me to a party at her home; I came home three days later and I said, ‘Boy, this is the business for me!’”

He began his career as an editor and assistant cameraman to renowned cameraman Lee Garmes, on the film Morocco (1930), directed by Josef von Sternberg. Director von Sternberg allowed him credit for the film The Devil is a Woman (1935) and the two shared the Venice Film Festival Award for Best Cinematography. He worked for Columbia on short features, including comedies of The Three Stooges and Charlie Chase. This gave him the excellent opportunity to learn how to shoot films quickly and efficiently. In addition to Paramount and Columbia, he worked at RKO, Universal, and 20th Century Fox, as well as for television studios.

In 1944, he established his reputation during the filming of The Lodger. The film’s female lead, Merle Oberon, had been in a car accident that had left her with facial scarring. Ballard invented a key light that was mounted on the side of the camera and washed out facial imperfections so that they would not be seen on film. He named the device the “Obie” for her and it became very widely used in the film industry. Ballard and Oberon were married from 1945 to 1949. He was hired by Howard Hughes to work on The Outlaw (1941); Hughes wanted him to use his talents to highlight Jane Russell’s two best attributes. Although filmed in 1941 and 1942, The Outlaw was not released until 1946, due to Hughes’ wanting the film to be perfect and the concerns of the film censors of the day.

Ballard continued to work with many of Hollywood’s finest directors, including Henry Hathaway, Budd Boetticher, Sam Fuller, Robert Wise, John Sturges, and probably most notably, Sam Peckinpah. He worked with Peckinpah on the TV show The Westerner (1960) and the films Ride the High Country (1962), The Wild Bunch (1969), The Ballad of Cable Hogue (1970), The Getaway (1972), and Junior Bonner (1972). Ride the High Country is considered to be one of the most beautifully filmed westerns ever made. Ballard won the National Society of Film Critics Award for Best Cinematography for his work on The Wild Bunch. He was also nominated for a Best Cinematography Academy Award for The Caretakers (1963). He worked on over 130 films during his career and was quite sought after and well respected. Ballard was involved in a road accident while riding his bicycle near his home; he died at age 84 in October of 1988. He was a widower at the time, and was survived by two sons, Tony and Chris Ballard.

Notes by Bruce Whittaker

Shot in just in eight days, Murder by Contract is a taut and tense little B-grade picture that many would-be filmmakers could learn from. Although made on a visibly small budget (inexpensive sets and locations, and not very picturesque), the film, a model of economy, holds one’s interest and attention with its rapid cutting and excellent sense of time.

Basically, the story is of a killer, hired to dispose of a Federal witness who is in protective custody. The job is tougher than first imagined because she never leaves her heavily guarded house. Actor Vince Edwards, who plays the hired gun, is a disturbingly malevolent figure with no emotional feelings for his victims. His justification is that his is a business, like any other. In fact, his goal, like many businessmen’s, is to earn enough money to buy a house! This coldly objective attitude to his job overcomes any moral dilemma he might feel. Here, the script hints at implications that, unfortunately, are not developed further—hints of hidden areas of corruption within a violent and aggressive society. Indeed, in this story of a hitman who wants to buy an expensive house, the acquisitiveness of American society is taken to its ultimate extreme. There is an undercurrent of ideas that, perhaps, could have been taken further; one such being the killer’s attitude towards women. He is very upset that the government witness is a woman, and is prepared to ask for more money. The reason for his fear (or frustrated desire?) of women is not known.

Director Irving Lerner makes intelligent use of actor Vince Edwards in, probably, his best movie role before, and since going on to, TV “glory” as Dr. Ben Casey, Dr. Kildare’s glowering opposition on the “tube.” The film’s tone is remarkably nonviolent for such a cold-blooded and violent theme, and Perry Botkin’s excellent guitar score makes a distanced, almost disembodied comment on the action. It is appropriately titled, “The Executioner’s Theme” and a recording of it was available, at one time. I will leave the last word on the film to director Scorsese, who lists it as one of his “guilty pleasures” in an article in Film Comment of September/October, 1978: “This is the film that has influenced me the most. I had a clip of it in Mean Streets but had to take it out; it was too long and a little too esoteric. And there’s a getting-in-shape sequence that’s very much like the one in Taxi Driver. The spirit of Murder by Contract has a lot to do with Taxi Driver. Lerner was an artist that knew how to do things in shorthand, like Bresson and Godard. The film puts us all to shame with its economy of style, especially in the barber-shop murder at the beginning. Vince Edwards gives a marvelous performance as the killer…. Murder by Contract was a favorite of neighborhood guys who didn’t know anything about movies. They just liked the film because they recognized something unique about it.”

Notes by Barry Chapman

Originally written for Film Buffs Series “A”, 1982-83 (Season 35) Sunday, January 30, 1983, Programme #6

Leave a Reply