Midnight Lace (1960)

Toronto Film Society presented Midnight Lace (1960) on Monday, August 13, 2018 in a double bill with Murder by Contract as part of the Season 71 Summer Series, Programme 5.

Production Company: Arwin Productions. Producers: Ross Hunter, Martin Melcher. Director: David Miller. Screenplay: Ivan Goff, Ben Roberts, based on the play by Janet Green. Cinematography: Russell Metty. Film Editors: Leon Barsha, Russell F. Schoengarth, William A. Lyon. Music: Frank Skinner. Art Direction: Robert Clatworthy, Alexander Golitzen. Set Decoration: Oliver Emert. Release Date: October 13, 1960.

Cast: Doris Day (Kit Preston), Rex Harrison (Anthony Preston), John Gavin (Brian Younger), Myrna Loy (Aunt Bea), Roddy McDowall (Malcolm), Herbert Marshall (Charles Manning), Natasha Parry (Peggy), Hermione Baddeley (Dora), John Williams (Inspector Byrnes), Richard Ney (Daniel), Anthony Dawson (Ash), Rhys Williams (Victor Elliott), Richard Lupino (Foster).

These days cineastes typically ascribe the authorship of a film to its director, but Midnight Lace is first and foremost a Ross Hunter production. Born Martin Fuss in Cleveland, Ohio, the former drama teacher would change his name in 1944 after arriving in Hollywood to pursue an acting career. By the 1950’s, Hunter had developed a head for the business aspect of the movies and found production work on a string of adventure films for Universal. This business acumen paid off and put him in the good graces of the studio where he would soon be promoted to staff producer, allowing him to develop a luscious style that reached its apex working with director Douglas Sirk on Magnificent Obsession (1954), All That Heaven Allows (1955), Imitation of Life (1959), and others. Hunter would produce light comedies such as Tammy and the Bachelor (1957), westerns such as The Spoilers (1955), and create a unique niche producing remakes of Hollywood classics like My Man Godfrey (1957) and Back Street (1961). Although his last theatrical production, the 1973 remake of Lost Horizon, was a legendary misfire Hunter’s films were generally a success with everyone…except for the critics.

The same can be said for the star of tonight’s feature, Doris Day. The perennial crowd pleaser Doris Day was fresh off the smashing success of her first collaboration with Ross Hunter Pillow Talk when she accepted this dramatic role. At this point in her career the cement of Doris Day’s cultural status had begun to set. By the time the tumultuous decade of the 60’s had ended Day would (seemingly) forever be known as the banal, cheerful girl next door—a real square. The elitist critics would regularly pan her down along with her most associated genres, the romantic comedy and the musical, while she would continue to be a success with the paying audience. Her sunny disposition made her synonymous with that most demeaning of smears: virgin. But to paraphrase Oscar Levant, “I knew Doris before she was a virgin” and so it goes that every Day has a night. For every couple of “typical” Doris Day pictures there were roles that revealed her turmoil—The Man Who Knew Too Much, Love Me or Leave Me, Young Man with a Horn, amongst others.

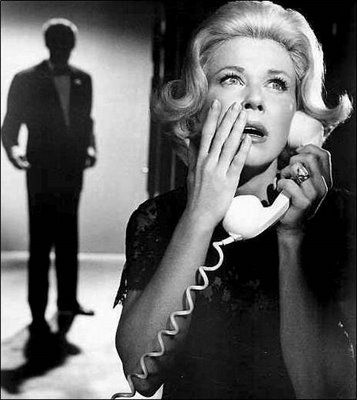

In Midnight Lace, which certainly fits into this latter category, Day’s character, an expat wife living in a posh London apartment, is put through relentless stalking. Day applied method acting techniques to generate the feeling of being terrorized by a man. According to her memoirs she “re-created the ghostly abuses of Al Jorden”—Jorden being her first husband, a Jekyll and Hyde personality; a darkly handsome, talented trombonist prone to violent fits of jealousy. She continues, “I imposed on myself that moment when I was pregnant and ill, and Al Jorden burst into the room, dragged me from the bed, and hurled me against the wall. I wasn’t acting hysterical, I was hysterical, so that at the end of that scene I collapsed in a real faint.” She wrote, “I just can’t walk away from a scene and shed my emotions.” So traumatic was this experience that Day would only make comedies for the rest of her career.

Ross Hunter said of his films, “The way life looks in my pictures is the way I want life to be. I don’t hold a mirror up to life as it is. I just want to show the part which is attractive.” The same could be said of Doris Day’s famous persona—her vitality and broad smile a temporary antidote to a world that tends to leave us exhausted and stone faced.

Introduction by Adam Williams

Midnight Lace (1960) was directed by David Miller and starred Doris Day, Rex Harrison, and John Gavin with an excellent supporting cast, including Myrna Loy, Herbert Marshall, Hermione Baddeley, and Roddy McDowell acting decidedly creepy as the housekeeper’s son. Perhaps not a first-rate thriller, Midnight Lace is a very good-looking film due, in part, to Academy Award-winning cinematographer Russell Metty (Spartacus, 1960). The London streetscapes are filmed like a travelogue and the visuals are further enhanced by well-appointed sets with tasteful and expensive furnishings. Throughout the film, the lovely Miss Doris Day is decked out in an exquisite wardrobe and accessories. Lovely, original jewelry pieces were designed by American jeweler David Webb, such as a diamond gondola. In the nightclub scene, watch for Myrna Loy wearing a statement necklace of green jewels beautifully complementing her red hair.

In the opening credits of the film, look for the trademark signature of designer Irene Lentz—mononymously known as “Irene”—who was coaxed back to film work by Miss Day herself to design the wardrobe for this film and another Day film, Lover Come Back (1961). Her work on Midnight Lace earned Irene her second Oscar nomination for Best Costume Design, Colour. In this film’s nightclub scene, Miss Day is wearing a floor-length gown encrusted in silvery-white bugle beads, an Irene creation worn by Miss Day at the 1960 Academy Awards. Also, watch Miss Day stand out in a crisp, crimson suit with matching hat, while the background extras are dressed in muted tones. Finally, look for the lovely lingerie piece, Midnight Lace, the namesake of the film.

When thinking of Hollywood’s Golden Age, Edith Head is probably one of the best-known names in costume design. However, although her name is not so well-known today, it was Irene’s designs that defined American couture in the 1930s and 1940s. She was famous for her tailored suits and flowing gowns; Irene is generally accepted as the designer of the “dressmaker’s suit”, a smart “power suit” popular with modern women in the late-1930s.

Born in Montana in 1901, Irene started in Hollywood as a bit-actress for Mack Sennett in 1921. Having been taught sewing as a child, she stopped acting and opened a small dress shop. Her first husband, one of Sennett’s production chiefs, died of tuberculosis in 1930, a mere eleven months after they were wed. After his death, Irene went to Europe to continue studying fashion design. When she returned, she opened a boutique on Sunset Boulevard that was patronized by the wives and daughters of Hollywood’s wealthy and elite. Her work garnered much attention from the film community, including Lupe Vélez (Irene’s first Hollywood customer), Marlene Dietrich, Loretta Young, Rosalind Russell, and Joan Crawford, who often wore Irene’s trademark smart suits, both on and off the screen. The designer’s first big break in film came when she was hired to create the gowns for Ginger Rogers for Shall We Dance (1937), followed by more work in films. During the 1930s, Irene Lentz designed the film wardrobes for such leading ladies as Hedy Lamarr, Joan Bennett, Claudette Colbert, Carole Lombard, and Ingrid Bergman, to name a few.

Irene met and married Elliot Gibbons, the brother of Cedric Gibbons, the head of art direction of MGM Studios. It was her second marriage and, reportedly, an unhappy one. In 1942, MGM appointed Irene as their executive designer after its chief designer left to open his own boutique. At MGM, Irene was designing for stars such as Greer Garson, Katharine Hepburn, and Judy Garland; she famously put Lana Turner in the high-waist shorts and bare-midriff top in The Postman Always Rings Twice (1946) and collaborated on swimsuits with Esther Williams. But by 1949, she had had enough with MGM and film work; Irene left to launch her own line for a broader market of women enamoured with her structured suit designs and bias, silk, soufflé gowns. By this time, she only did freelance film work.

Unfortunately, like many gifted artists, Irene ended her life in suicide, bringing to mind the recent deaths of designer Kate Spade and chef Anthony Bourdain. By 1962, Irene was battling health issues and a drinking problem. According to Doris Day, Irene had been distraught over the death, the year before, of her “one true love”, Gary Cooper. (It isn’t known whether or not Irene and Cooper had ever been intimate.) Although her latest fashion show had received rave reviews, on November 15, 1962, Irene checked into the Knickerbocker Hotel in Los Angeles. After a night of drinking vodka (two pints), she threw herself out of the eleventh-floor window only to land in an awning below; her body was found later that night. Her suicide note read: “I’m sorry. This is the best way. Get someone very good to design and be happy. I love you all, Irene.”

Irene’s first Academy Award nomination was for Best Costume Design, Black-and-White in B.F.’s Daughter (1948), starring Barbara Stanwyck and Van Heflin. Her last film production was A Gathering of Eagles (1963). In 2005, Irene Lentz was inducted into the Costume Designers Guild’s Anne Cole Hall of Fame.

Notes by Bruce Whittaker

Leave a Reply