Bluebeard (1944)

Toronto Film Society presented Bluebeard (1944) on Monday, July 30, 2018 in a double bill with Mystery of the Wax Museum as part of the Season 71 Summer Series, Programme 4.

Production Company: Producers Releasing Corp. Producer: Leon Fromkess. Associate Producer: Martin Mooney. Director: Edgar G. Ulmer. Screenplay: Pierre Gendron, based on an original story by Arnold Phillips & Werner H. Furst. Cinematography: Jockey A. Feindel, Eugen Schüfftan. Art Direction: Paul Palmentola, Angelo Scribetta. Production Design: Eugen Schüfftan, Edgar G. Ulmer. Supervising Film Editor: Carl Pierson. Music Score Composer & Conductor: Leo Erdody. Marionettes: Barlow & Baker. Release Date: November 11, 1944.

Cast: John Carradine (Gaston Morel), Jean Parker (Lucille Lutien), Nils Asther (Inspector Jacques Lefevre), Ludwig Stossel (Jean Lamarte), George Pembroke (Inspector Renard), Teala Loring (Francine Lutien), Iris Adrian (Mimi Robert), Henry Kolker (Deschamps).

Director Edgar Ulmer seems to have harbored much sympathy for the obsessive artist Gaston Morel, played by David Carradine, and he poured all of his own obsessive energy into what he later called “a tremendously challenging picture.” He had a long-standing interest in the Faust legend, and placed it near the start of the film, a story within a story, using his own deep knowledge of Goethe’s (Gote’s) tragic play, Charles Gounod’s opera and F.W. Murnau’s great 1926 cinematic adaptation to accomplish this. Moreover, the Faustian bargain, the selling of one’s soul—or, in the case of Gaston Morel, one’s art—to the devil, was something with which Ulmer could no doubt identify. Just like the character, Ulmer was an artist searching in vain for salvation in Hollywood.

But irrespective of the Faust material, the market-driven hope of the production company PRC was that Bluebeard would cash in on the Jack the Ripper trend set by 20th Century-Fox’s The Lodger released earlier that year, which incidentally TFS will be showing on August 20th.

By the time the principal photography for Bluebeard began on the last of May 1944, Ulmer had signed a one-year contract with PRC. Yet the genesis of making Bluebeard lay a full decade earlier, when he was still at Universal and the film’s cinematographer Eugen Schüfftan was still living in Paris. In April 1934, the Hollywood Reporter announced, prematurely as it turned out, that Ulmer was slated to direct the picture, “an elaborate production,” for Universal. But studio patriarch Carl Laemmle (Lemlee) severed all ties to the director after his work was completed on the film The Black Cat due to apparently Ulmer’s misconduct. And ten years later, producer Leon Fromkess, although a great champion of Ulmer, was not keen on acquiring the project for PRC, especially when it came to the play-within-a-play Faust opera that Ulmer insisted was essential to the story. For Fromkess the Faust sequence was little more than “stuffy high-brow music and marionettes.” Yet on the question of classical music Fromkess proved just as mistaken as Laemmle (Lemlee) had been before him.

In the end, Bluebeard was regarded as a prestige film for Fromkess and PRC, and it ultimately brought greater attention to the little studio, its head producer and its star director. As the contemporary review in the Hollywood Reporter regarded the film a success, its headline banner summed it up with “PRC Bluebeard Excellent, Distinctive Class Film: Ulmer Mega Scores, Carradine Fine”.

Sourced from Edgar G. Ulmer: A Filmmaker at the Margins by Noah Isenberg (2014)

Introduction by Caren Feldman

Edgar G. Ulmer’s directorial career started impressively enough, as one of the several directors of the classic German documentary Menschen am Sonntag (1930), which launched the careers of Curt and Robert Siodmak, Fred Zinnemann, and Billy Wilder. Prior to that, he was the set designer (often uncredited) for a number of notable Fritz Lang films, including Metropolis (1927), and also served as assistant to F.W. Murnau. His Hollywood career showed early promise with the Boris Karloff/Bela Lugosi vehicle The Black Cat (1934), often considered one of the best of Universal’s horror cycle. But Ulmer was not cut out to be a team player in the studio system. He soon found himself on “poverty row”, where—working with almost no budgets, no time, and often starting with nothing more than a title—he found the kind of freedom he preferred. With little or no recognition and resources, he managed to stamp a personal artistic signature on his work, noticed by the French auteurist critics of the 1950s and 1960s. Since then, he has come to be regarded as an artist of a unique, if offbeat, vision, and has helmed several influential films, including the classic minimalist noir thriller Detour (1945).

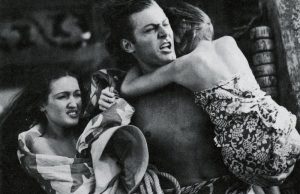

Bluebeard is considered one of Ulmer’s best pictures. Originally intended as a follow-up to his macabre classic The Black Cat, Ulmer had to wait a decade and work with John Carradine, instead of Boris Karloff as planned. Carradine, however, came through with probably his best performance as a painter and puppeteer who has the nasty habit of killing his models. Ulmer was his own set designer for his movie, recreating his beloved Paris on the lot of Poverty Row studio PRC. Although shot in only six days, it displays a high level of acting and camera work and contains a particularly notable and effective sequence, a puppet show version of the Faust legend. Although he says PRC was unhappy with the finished product, Ulmer was proud of his “lovely picture,” which, he later told admirer Peter Bogdanovich, “earned tremendous money in France.”

The legend of the murderous Bluebeard had already been a folktale by the time it was written by Charles Perrault in 1697. The cautionary tale of the dangerous husband/lover, purportedly based on a real-life serial killer of the 15th century, took many forms, over the years. In films, the character has been everything from a deranged World War I pilot (Richard Burton in the 1972 version) to a loving Parisian father who seduces and kills women in order to feed his brood (Charles Denner in Claude Charbrol’s Landru, 1963). Charles Chaplin directed and played in a version of the legend in Monsieur Verdoux (1947) and Ernst Lubitsch spoofed it in Bluebeard’s Eighth Wife (1938), starring Gary Cooper and Claudette Colbert.

His role in this film is reportedly John Carradine’s personal favourite. A prolific player whose career spanned hundreds of films over about 60 years, Carradine rarely got the chance to carry a film as he does here, although he received praise for a number of classical stage roles, such as Hamlet and Malvolio. On screen, he was always a quirky, often unconventional character lurking in the background of many fine films. Part of John Ford’s stock company, he appeared in eleven of that director’s pictures, as well as a large number of other westerns; enough to earn him induction into the Hall of Great Western Performers of the National Cowboy and Western Heritage Museum, in 2003. But despite his range and talents, he is most often—and rather unfairly—associated with the horror genre; mostly because of his gaunt looks and distinctive voice. He is the father of actors Keith, David, and Robert Carradine.

Much of the cast will be familiar to connoisseurs of character actors and supporting players. Nils Asther (Lefevre), a Dane often cast in more ethnically “exotic” roles, was the title character in the Frank Capra-directed, Barbara Stanwyck film The Bitter Tea of General Yen (1933), and in the 1920s and early-1930s, also played leading man to Garbo, Crawford, Pola Negri, and others. Early in her career, Jean Parker (Lucille) had a promising start as Beth, the doomed sister in Little Women (1933), opposite Katharine Hepburn. While she never achieved top stardom, she worked in film and on stage into the 1970s and was also an accomplished clothes designer. Iris Adrian (Mimi) was one of Hollywood’s busiest character actors and bit players. The year before this movie, she played one of the smart-talking strippers in the Stanwyck mystery-comedy Lady of Burlesque (1943). Late in her career, she turned up in a string of Disney hits, including The Love Bug (1968) and Freaky Friday (1976). Austrian-born Ludwig Stossel (Lamarte) had a 30-plus-year career in film and television, laying a range of Germanic characters for everyone from Fritz Lang to George Cukor and turning up in such films as Casablanca (1942), The Merry Widow (1952), and Elvis Presley’s G.I. Blues (1960), Stossel’s last picture.

Notes by Peter Poles

Leave a Reply