Queen Elizabeth (1912)

Toronto Film Society presented Queen Elizabeth (1912) on Monday, October 23, 1967 as part of the Season 20 Monday Evening Silent Film Series, Programme 1.

(Main Auditorium, UNITARIAN CHURCH, 174 St. Clair West)

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

Programme No. 1

Monday October 23, 1967

H O W I T A L L B E G A N

-or-

From Penny Arcade to Old Broadway in Less than Twenty Years

Representative samples from the Cinema’s infancy and formative years–an album of its baby pictures, so to speak.

1): The Execution of Mary Queen of Scots (U.S.A. 1893)

Directed by William Heiss for the Edison company.

Cast unknown.

2): Washday Troubles (U.S.A. 1895)

Directed by Edmund Kuhn.

Cast: Mrs Edmund Kuhn and others.

3): A Trip to the Moon (France 1902)

Produced and directed by Georges Méliès.

Photography by Lucien Tainguy.

Cast: Georges Méliès, dancers from the Théatre du Chatelet, acrobats from the Folies Bérgères.

4): The Great Train Robbery (U.S.A. 1903)

Produced by the Edison company.

Directed by Edwin S. Porter.

Cast: George Barnes, Gilbert M. (“Broncho Billy”) Anderson, A.C. Abadie, Marie Murray and others.

5): Rescued by Rover (Britain 1905)

Produced and directed by Cecil Hepworth.

6): The Pumpkin Race (France 1907)

Directed by Emile Cohl

7): Possibilities of War in the Air (Britain 1910)

Produced by the Warwick Trading Company, London.

Directed by Charles Urban.

INTERMISSION

8): Sarah Bernhardt in Queen Elizabeth (France 1912)

Directed by Louis Mercanton.

Cast: Sarah Bernhardt, Lou Tellegen and others.

In four reels.

* * *

NOTES

“Prima le parole, doppo la musica!”–first the words, then the music; so declares the Poet in Strauss’s opera “Capriccio”, upholding the librettist’s share in the creation of an opera; to which of course the Composer retors “Prima la musica, doppo le parole“. Significantly, “Capriccio” ends without a resolution of the argument.

If Opera is the offspring of the marriage of Drama and Music, the Film is the child of Science and Art. The Scientist invents the mechanism; the Artist comes along and puts it to his own use. Almost every artistic innovation has been the outcome of some mechanical improvement. Prima la scienza, doppo l’arte. But if science exists to serve the artist, then is it not “prima l’arte, doppo la scienza”?

Mechanically, the motion picture as we know it arrived in the closing decade of the 19th century, and was the outcome of the blending of three previous inventions: the magic lantern, photography, and those little 19th century optical toys, such as the Zoetrope and the Fantoscope, by which little hand-drawn figures appeared to run and jump–the practical application of the theory of the Persistence of Vision, first advanced in 1824 by Peter Mark Roget (of Thesaurus fame). It was Thomas Edison and his assistant, William K.L. Dickson, who in 1889 achieved the first moving picture camera–the “Kinetograph” they called it–and the first apparatus for viewing the result: the “Kinetograph”. Edison’s aim was simply to improve his invention of the phonograph by adding the video to the audio; and interestingly, their first crude but successful trial run was talking picture. Talkies, however imperfect and unready, can thus be said to have preceded silent films. Another premature anticipation of the future: the camera was driven by a battery-powered motor, just like your up-to-date home movie camera . . though of course the resemblance ends there.

But the Kinetoscope was not a projector; it was more like a Viewmaster, a mechanical peepshow. You put your eye to the lens, and as the film whirled past between your eye and the flashing light, you marvelled as you watched photographs that moved like living people. Furthermore, the film wasn’t on a reel; it was joined end-to-end on a series of rollers,–in other words, it was a “loop”, like those hundreds of little films you saw in so many of the pavilions at Expo. (Plus ça change, plus c’est la même chose. Is film history itself on a loop?) It ran at an incredible speed of 48 frames per second, and as each film was only fifty feet long, the duration was very short. But this crude peepshow was the father of all our modern moving pictures.

If you are already interested in the early beginnings of the movies, you have probably already discovered Terry Ramsaye’s “A Million and One Nights” where a full account is set forth in minute detail–at the end of the first 400 pages you still haven’t reached the 20th century! But thanks to the author’s racy narrative style it is eminently readable, and if your interest in this period is aroused by tonight’s program, we recommend you read this book–preferably supplemented by other books such as C.W. Cerman’s “Archeology of the Cinema” (1965) which is not nearly so detailed but does fill in many of the gaps, and furthermore is profusely illustrated.

In the meantime, for those who joined this series to see Rudolph Valentino and not because you are students of film history, the following is hasty and over-simplified sketch which may (if you care to read it) help to fil you in with a rough-and-ready background to the films you will see tonight.

* * *

Edison had more important things to work on than a scientific toy that made pictures move. He and Dickson worked only intermittently to make the necessary improvements in its functioning; not till 1891 did he patent it (and then only in America; the European patent didn’t seem to him to warrant the extra cost); and not till 1893 was a company set up to handle it commercially. They wanted to introduce it at the Chicago World’s Fair of that year (a thesis could be written on the part played in the development of the cinema by World Fairs), but Edison was unable to deliver the machines and the supply of films in time, and it was not until April 14, 1894, in New York, that the first Kinetoscope Parlor in the world was opened. It caught on like wildfire, and soon every major city in the United States (and Canada? our American-based reference books don’t say) had its Kinetoscope Parlors where the public stood in long lines to await the opportunity to put their nickels in the slot and watch the pictures that moved–like small children raptly watching the television set, commercials and all.

(A rival company came out with a Mutoscope, in which the pictures were printed on cards mounted on a sort of paddle wheel which you cranked; and this system outlived Edison’s Kinetoscope, and may still be seen in cheap penny arcades. Incidently, this “Mutoscope and Biograph Company” was to become one of the most important film companies of the pre-1914 era–the company where D.W. Griffith worked for so many years and developed his craft).

Not surprisingly, it wasn’t long before people began thinking “Wouldn’t it be great if these pictures could be projected on a screen, like a magic lantern, so that they could be seen by many people all at once instead of by only one at a time!” And so it is not surprising that within the next year or two more than half a dozen different inventors, working independently, had all produced moving picture projectors–not only in the States but in France and England (where Edison’s Kinetograph and Kinetoscope were unprotected by copyright). Chronologically the first seems to have been that of the Lumière Brothers (an appropriate name!) of France, who held a private demonstration of their combined camera and projector, the Cinématographe (a new word), as early as March 1895. Their first public exhibition took place in Paris on December 28. (In April 1895 a New York outfit and presented the very first public exhibition of screened motion pictures in the world, but their machine was very unsatisfactory). Edison had been dead set against projection, believing that over-exposure of these living pictures would quickly dry up the vogue, but his company pressured him into launching his own projection machine (incorporating the improvements of Thomas Armat); and on April 23, 1896, Koster and Bials’ Music Hall on 34th Street (where Macy’s now stands) included a brief program of films as part of its vaudeville bill. The audience reaction to these life-sized moving pictures was tremendous. (The program included a scene of an express train coming around a corner, which nearly caused a panic). Movies were here to stay.

Two months later, a rival music hall in New York imported a Lumière Cinématographe and a supply of Lumière films, and likewise drew full houses. The Lumière equipment was somewhat different from Edison’s. It was cranked by hand instead of by a battery motor; and whereas Edison’s film rat at a speed of 48 frames a second, Lumière’s film (though likewise 35 mm wide) ran at a mere 16 frames per second. This was obviously much more economical of film stock, and it is not surprising that the industry quickly converted to this standard. Sixteen-a-second remained the official (though not always the actual) speed of films until the coming of sound, when the standard officially became 24 frames per second. (16 fps is still the standard for most 8mm cameras).

Prima la scienza, doppo l’arte. In order to provide a supply of films for the Kinetoscope parlors, Edison in 1893 built a studio at his plant in West Orange, N.J., and set Dickson to work making 50-foot films. The very first film was of a man sneezing; but current vaudeville acts provided most of the film fodder: dancing girls, trained bears, contortionists, bits from current stage successes, stars like Annie Oakley (the original, not Ethel Merman) and Sandow the Great doing parts of their acts; cock fights; bucking bronchos; and more dances. (A prize fight movie was the first blockbuster). Each film lasted only a fraction of a minute; but the medium itself was the message, and the public got the message, and happily poured a fortune into the slot machines, and later, into the box-offices of the vaudeville houses and travelling showmen’s tents that presented moving pictures on a screen. In France the Lumière Brothers likewise fascinated their audiences with brief moving pictures of people doing things. But there was an appreciable difference between the Edison films and the Lumières. Prima la scienza, doppo l’arte. The Edison camera was a “vast bulky device of about the dimensions of a large dog house”, with the weight and portability of a piano, and though they could carry it about in a wagon when necessary, it was much simpler to bring performers out to West Orange to Edison’s Black Maria (as the tarpaper-covered studio was dubbed by his staff). The hand-cranked Lumière camera, however, was light enough to be carried in one hand; consequently they could and did venture outside to record bits of real life: workers leaving the factory, a train entering a station, baby having breakfast, and so on,–cinéma vérité, if you like.

The biggest box-office items in those days were “Annabelle the Dancer” and “The May Irwin-John C. Rice Kiss”; they were always in demand. The first two items on this evening’s programs are further samples of the peepshow fodder produced in the Black Maria. The Execution of Mary Queen of Scots is said to date from 1893, which would place it among the films that were produced in readiness for the opening of the first Kinetoscope Parlor in 1894. If so, however, it would have been filmed at 48 frames per second. This print, of course, may be a later adaptation for modern projectors; or perhaps the date is wrong. (The film is certainly not listed in the Kinetoscope Company’s catalogue issued in October 1894). I gather that the film is the concluding scene of “Mary Stuart”, a play that was popular in the 1880’s. If so, this must be the earliest example of modifying a stage play to take advantage of the special resources of the movie camera. (For those who haven’t seen it, we refrain from revealing the grisly climax).

In addition to actualities and items from current shows, the peepshows and early screen films included improved slapstick incidents, such as Washday Troubles and other similar side-splitting comedies.

The early films were completely wordless –originally not even the title of the film appeared on the screen (cf. the films at Expo 67)–and hence were ideal for international distribution. Audiences on both sides of the Atlantic were soon seeing films (frequently pirated) made in England, France, the U.S. and elsewhere almost as soon as they came out; and thus film makers began learning from each other.

The films of Georges Méliès soon began delighting audiences everywhere. Méliès (1861-1938) was a professional magician with his own theatre in Paris at the time that he attended the historic first public showing of the Lumières’ films on December 28, 1895. Fired by its possibilities, he soon acquired his own Cinématographe and by the following April he had made his first film and shown it in his theatre. Being a magician by trade, he soon discovered the movie camera’s possibilities for the trick photography–from simple stop-motion to double exposures, reverse action, fast and slow motion, as well as the now standard vocabulary of the fades and dissovles–all of which helped him to indulge his love of fantasy.

Méliès advanced film art in yet another way. Like everyone else he began with single scenes; but by 1900 he became more ambitious and ventured to tell the story of Cinderella by the “artful arrangement” of several different scenes. Nowadays it seems incredible that after seven years of existence the film had never before told a story (other than very brief incidents, such as the two samples on today’s program). As long as films were confined to fifty foot lengths, of course, there wasn’t much else they could present. Georges Méliès, with Cinderella, is credited with the first narrative film. It was the beginning of narration, and also the beginning of longer films, and A Trip to the Moon of 1902 (his 400th film) was an unprecedented 825 feet in length–three times as long as the average film of its day–and became a great popular success. (other Méliès films: The Doctor’s Secret, The Damnation of Faust, An Adventurous Automobile Trip, The Merry Frolics of Satan, The Palace of the Arabian Nights, The Conquest of the Pole and many, many others).

For all his pioneering in narration and his exploitation of the camera’s tricks, Méliès never even considered freeing his films from the confines of a theatre stage. The action all takes on this stage, in front of painted sets, and the camera watches immobile from the royal box. But this bothered nobody in those days–what other precedent was there?–and the films delighted with their fantasy, imagination and zaniness.

Narrative films were soon taken up by other film makers, in England, America and elsewhere. In the United States, Edison’s films after 1896 were being made by his cameraman, Edwin S. Porter, who in 1902 followed Méliès’ example and produced the first American narrative film, The Life of an American Fireman. (George Pratt, of Eastman House in Rochester, believes Porter was not so much influenced by Méliès as simply remaking for American audiences the English film Fire! (1901) by James Williamson). Whatever its antecedents, this little film (which we showed two years ago) broke new ground, for it was made not only by shooting but also by editing: reassembling shots made at different times and in different places, to produce a dramatic narrative. (See Lewis Jacobs’ “The Rise of the American Film” for a scene-by-scene description of this historic film).

Porter carried these principles to greater fruition the following year when he made The Great Train Robbery (1903). Even today this little ten-minute film is still genuinely entertaining, in its own little primitive way; but in its day, in the context of what ordinary films were like, it had a powerful impact that made it box-office bonanza for years to come. It was the Birth of a Nation and Gone With the Wind of its day; and it probably had more influence on other film makers than any other single film. Its indoor scenes are still stagey; but notice the freedom from stage convention in the outdoor shots. (It took film makers many years to get it into their heads that whereas on the theatre stage one entered and exited left or right by sheer physical necessity, in films there was nothing to prevent actors from moving toward or away from the camera). But above all, it is this film’s method of telling its story that was its biggest advance. Movies, as Jacobs has said, “would have remained a novelty with little social or artistic significance had not Porter, or someone else, discovered the film’s adaptability to being cut up and rejoined for narrative and interpretive purposes”.

English film makers had shown great imagination right from the very beginning, and not surprisingly they were quick to take up the narrative film. Among these men was Cecil Hepworth, whose Rescued by Rover appeared in 1905 and became an international favorite. (Incidently there’s a copy of Hepworth’s memoirs on the shelves of the Theatre Section of the Toronto Public Library). Charles Urban, the director of Possibilities of War in the Air (1910), was an American who settled in England around 1898. He was a scientist as well as an artist: he was co-inventor (in 1906) of Kinemacolor, a successful process for motion picture color photography which was the basis of almost all subsequent color processes. Not surprisingly we find him in this film indulging in science-fiction speculation (undoubtedly much more scientific than Méliès’ lunar space trip)–and incidently giving us an idea of the aeronautical folklore of the period.

At the time The Great Train Robbery was made, ten years had passed since Dickson began filming sneezes and dancing girls for Edison’s Kinetoscope. Movies were now beginning to be shown in theatres of their own. At the turn of the century peepshows continued to flourish, for screen projectors were expensive and hard to come by. But late in 1900 a strike of vaudeville artists was broken because the theatres laid in supplies of projectors and films and continued to do business. After the strike was over they unloaded these projectors onto the eager arcade owners, who set aside a section of their amusement parlors, rented chairs, and began showing films. Presently, from 1902 on, more and more of these arcades decided to concentrate on movies alone. Finally in 1905 there opened in Pittsburgh a movie house which, though converted from an empty store like most of the others, was given a more luxurious look and the innovation of a piano accompaniment, and a new name specially coined for it: the Nickelodeon. With The Great Train Robbery as an opening attraction, the venture was a roaring success; and a new boom began. the name and the idea caught on; nickelodeons sprang up everywhere, till 1903 there were nearly ten thousand all over the country. The low admission price of 5¢ made the movies the ideal (indeed almost the only) entertainment for the underpaid working classes, who found each little program of short films an absorbing adventure.

Distribution methods were changing too. Originally each exhibitor, whether peepshow owner, travelling showman or music hall proprietor, had bought his films outright. Eventually they took to swapping their used films among each other, and in 1902 the first exchange was set up for this purpose; and it wasn’t long before there evolved the present system of renting the films from a central distributing company.

In France, other companies besides those of Méliès and the Lumières had sprung up, notably those of Charles Pathé and Jules Gaumont, names still familiar. Directors like Ferdinand Zecca and Emile Cohl expanded the Méliès tricks into mad little farces that were wildly comical in themselves, and were of great influence on Mack Sennett (by his own admission). Emile Cohl’s The Pumpkin Race (1907) is a classic example.

But in that same year, 1907, another company was formed in France which had an enormous international influence, though it promptly undid all the advances in film narration technique, all the cinematic discoveries that had been gradually made during the previous ten years as to the best way of using the motion picture camera to tell a story. For very understandable reasons, movies in all countries had been almost the exclusive property of the lower classes, to whom, with its simple content and low admission price, it had the greatest appeal. The educated classes, once the initial novelty wore off, soon became tired of dancing girls, fire fighters, and trains coming into a station, and returned to more intellectual pleasures, leaving the movies to the masses. No self-respecting person even dreamed of going to a nickelodeon–for much the same reason that his opposite number wouldn’t seriously dream of reading comic books.

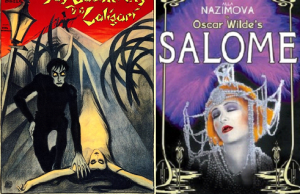

But now a company was formed in France with the purpose of appealing to this class. They would produce artistic films, and accordingly they called themselves Le Film d’Art; and since “art” to them meant the venerable art of the Theatre as they had known it all their lives, they turned to the Comédie Française and persuaded these august actors to perform their successful play “The Assassination of the Duc de Guise” for the movie cameras, and in 1908 this was presented with great éclat at a real theatre, with an orchestra playing a score specially written by no less a composer than Camille Saint-Saens. That the film consisted of actors making the larger-than-life gestures of the stage and silently mouthing their lines didn’t seem to bother anyone. This was Great Art, already familiar from the theatre. But it did have the effect of making films respectable, even though for the wrong reasons, and attracting audiences who would never have ventured into a cheap movie house to see such vulgar slapstick comedies as Fun After the Wedding or The Pumpkin RAce or simple melodramas like Rescued by Rober or A Daring Daylight Robbery. And for the next five years it had a great influence. On both sides of the Atlantic classic plays and novels were brought to the screen, however crudely, and the Film d’Art company in particular brought numerous stage celebrities before the cameras to reenact their great roles. Sarah Bernhardt in particular was most cooperative: “This is my one chance for immortality!” she declared hopefully.

Film makers in the United States were hobbled by the firm conviction held by the distributors that audiences couldn’t sit through any film longer than one reel (about 15 minutes); but in Europe films gradually began to expand in length to two reels, even three reels. (Imported to the United States, these were released in installments; till finally, in 1911, D.W. Griffith’s first two-reel picture was–by public demand–shown as a unit; and the two-reel movie then became the norm). The Italian cinema began going in for multi-reel costume spectaculars, such as The Fall of Troy (1910) in three reels, the super-colossal Quo Vadis, an unprecedented nine-reel film running two hours, and Cabiria (1913)–which we showed in our 1962-63 season.

In particular, two long films from Europe were presented in North America in spite of the establishment’s opposition, and proved such box-office hits that resistance to “feature” films was completely cracked, resulting in a shorts-to-features revolution (1913-14) that was fully as disruptive an upheaval as the silents-to-talkies revolution of 1928. These two films were Queen Elizabeth (1912) and the above-mentioned Quo Vadis, which began a 22-week run at the Astor Theatre in April, 1913.

When Queen Elizabeth was released in France it created such a great impression that the American rights were quickly purchased by a company formed in New York for the purpose, headed by Adolph Zukor, a Hungarian immigrant who had drifted from the fur business into show business, Edwin Porter (who had made The Great Train Robbery nine years before), and the distinguished theatre man, Daniel Frohman. The company was called “Famous Players in Famous Plays” (obviously patterned after the Film d’Art set-up), and at the moment this imported film was their only asset. But Frohman presented it not in a 5¢ nickelodeon but at his Lyceum Theatre on Broadway, on July 12, 1912, at an impressive and unprecedented (for a film) dollar a head, with all the glittering pomp of a new stage premiere; and the carriage trade responded. Thanks to the prestige of the divine Sarah, this was a film that was okay to see; and as withDuc de Guise in France five years before, it was the beginning of a grudging respectability for the lowly movies. And by the time Queen Elizabeth had gone the rounds of the country, it turned in a handsome profit, and Zukor’s Famous Players company set about producing other films starring famous stage celebrities who, with Bernhardt setting the example, no longer feared loss of face. And as everyone knows, Zukor’s company is still making pictures, though it is now called Paramount, while the Famous Players name is still retained by a chain of movie theatres.

It is ironic that a film which did nothing for the art of the cinema should have done so much for cinema history. Queen Elizabeth was one of Film d’Art’s reverent transfers to the silent screen of an outstanding stage play, and Sarah Bernhardt (67 years old when it was made) gave the same performance as she was used to giving on the stage, unaware that the intimate camera has no use for the exaggerated gestures so necessary in a large auditorium. Her greatest asset had always been her golden bell-like voice, and she did nothing to compensate for its absence. Furthermore, because of her injured leg (which four years later had to be amputated) she was by this time unable to walk without support, so that her very movements were restricted. In spite of Bernhardt’s fond hope, the films she made did nothing to immortalize her art; on the contrary, they jeopardize her great reputation, which was obviously not made on what we see here. But what else have we got? It may be only a fragment, a torso, but for anyone interested in the celebrated and fascinating Sarah Bernhardt, the opportunity to see this imperfect relic is still worth the effort required or making allowances. Add in your imagination her voice, and you may at least roughly approximate how she must have performed in her proper milieu, the theatre. (Contemporary audiences, familiar with her, could do this more easily; hence, no doubt the treat popularity of the film in its day).

(Besides Queen Elizabeth, Film D’Art filmed three other Bernhardt vehicles: La Tosca (1908), Camille (1911) and Adrienne Lecourvreur (1912). In 1916 she made Mothers of France and in 1923, on her deathbed, La Voyante, in which she was again directed by Louis Mercanton. In addition, the dueling scene from Hamlet was filmed back in 1900).

Lou Tellegen (1881-1934) was her leading man on the stage at this period. He later went to Hollywood where he was moderately successful for many years. He was better known for his good looks than for acting ability, but no one seems to have had a good word to say for him as a person.

* * *

A note on subtitles: As we pointed out earlier, the first films didn’t even have identification titles, let alone what came to be called (for want of a handier word) “subtitles”. In many places where early movies were exhibitied, a commentator was on hand to explain the story as it unfolded on the screen. This no doubt is the origin of the practice that crept in of inserting printed captions for the same purpose. Notice in this 1912 picture how every scene is introduced by a subtitle explaining what is about to happen. This seems to have been standard practice at that period; we find Griffith still making much use of it in The Birth of a Nation (1915). History doesn’t record who the bright genius was who first used a “subtitle” to supply the unheard dialogue, nor when; but the practice seems to have started relatively late, and was used very sparingly at first.

* * *

We have made our way through the first twenty years of the cinema, from primitive peepshow to the plush seats of the proud legitimate theatre. We are ready now to approach the first great screen masterpiece with something like the eyes of its contemporaries. The Birth of a Nation will be presented at our next showing: Monday, November 20, 1967, at 8:15 pm.

Notes by Fraser Macdonald

Leave a Reply