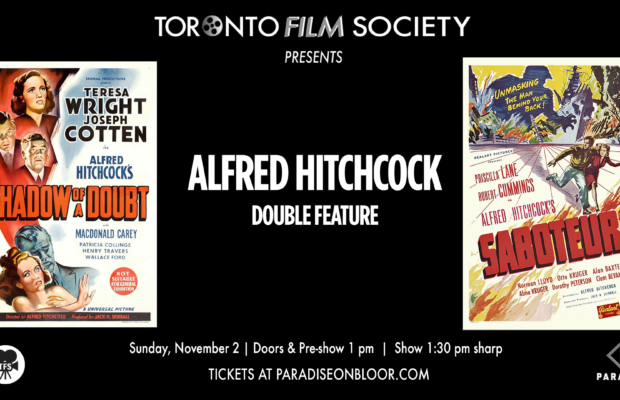

Shadow of a Doubt (1943) and Saboteur (1942)

Toronto Film Society presented Shadow of a Doubt (1943) on Sunday, November 2, 2025 in a double bill with Saboteur (1942) as part of the Season 78 Series, Programme 1.

SHADOW OF A DOUBT (1943)

Production Company: Skirball Productions. Produced by: Jack H. Skirball. Directed by: Alfred Hitchcock. Screenplay by: Thornton Wilder, Sally Benson, Alma Reville. Cinematography: Joseph A. Valentine. Editing: Milton Carruth. Music: Dimitri Tiomkin. Released January 12, 1943. Running time: 108 minutes.

Cast: Teresa Wright (Charlie Newton), Joseph Cotton (Charlie Oakley), MacDonald Carey (Jack Graham), Henry Travers (Joseph Newton), Patricia Collinge (Emma Newton), Hume Cronyn (Herbie Hawkins).

Alfred Hitchcock often cited Shadow of a Doubt as his favorite among his many films. The film stands as a turning point in his career, marking his full integration into Hollywood filmmaking while retaining the psychological precision of his British thrillers. A collaboration between him, playwright Thornton Wilder, screenwriter Sally Benson, and his wife Alma Revelle, the film is one of the first to portray evil hidden in plain sight.

Wilder brought a distinct American sensibility, the tension between idealized domestic life and the chaos lurking beneath it, while Hitchcock grounds the suspense in the real textures of a California town, using natural light and local extras to heighten authenticity. The realism of the setting makes the encroaching evil all the more unsettling. The film combines small-town realism with psychological tension, and one of its great qualities is to put its serial killer, played by Joseph Cotten, within the context of a family. He’s not an isolated man, not a weirdo or someone completely removed from society; on the contrary, he’s a beloved brother and uncle, a charming family man who’s also a murderer. What the film did so well is to present the message that evil can be everywhere, including our own homes.

The protagonist is not the killer, but his niece, Charlie (Teresa Wright), who shares the same name with her beloved uncle. A teenager suffocated by the dullness of everyday life in a seemingly peaceful community of Santa Rosa, Charlie is delighted when her uncle arrives for a visit. She’s certain he’ll bring the excitement and fun she’s been craving for, without knowing he’s on the run from the police. He’s known as the “Merry Widow Murderer”, and he’s killed 3 wealthy widows already.

Uncle Charlie’s charismatic presence electrifies the household. He’s adored by his sister Emma (Patricia Collinge), who considers him the family’s shining star. Hitchcock does a great job separating the initial joy of his charismatic and generous presence by infusing the screen with warmth through bright, open compositions and domestic harmony, contrasting sharply with the shadowy, low-angle shots that begin to appear as the story progresses.

As the days pass, though, something doesn’t feel right, and Charlie is the only one to pick up the signs. Uncle Charlie grows irritable, avoids questions, doesn’t want his picture taken, and reacts strongly when murder is mentioned. But her turn starts with a gift given by her uncle. A ring, engraved with the initials of another woman is the tipping point that makes her begin to suspect that something horrifying hides in the shadows. Her idealized vision of him collapses as she realizes he may be the very killer the detectives in town are quietly hunting.

Hitchcock masterfully builds suspense through silence, glances, and the weight of unspoken knowledge. The film’s tension lies not in action but in psychology. Charlie’s increasing suspicion on her uncle transforms what began as affection into fear, and her struggle to preserve her family’s innocence becomes a battle for survival. The tone shifts when Uncle Charlie realizes she knows what he’s done, and goes from subtle menace to direct threat, going to the point of him trying to kill her in a couple of occasions. The final confrontation, inside a train, ends the films with an ironic punch, becoming one of the richest in his filmography.

Symbolism deepens the psychological texture of the film. The ring, with its telltale engraving, becomes a token of both affection and guilt, the object that bridges intimacy and horror. The staircase, often used by Hitchcock as a visual metaphor for moral descent, appears repeatedly in moments of danger. Trains, another Hitchcock trademark, embody transition and threat—the movement from safety to peril, from illusion to revelation.

Enhancing the symbolisms, both Charlies serve as mirrors of one another. Their shared name and affectionate bond emphasize Hitchcock’s recurring theme of the double – the idea that good and evil, innocence and corruption, coexist within the same human soul. Young Charlie’s journey from naivety to awareness parallels her uncle’s descent from charm to monstrosity, suggesting that moral darkness is not foreign but latent in all of us. Hitchcock’s camera reinforces this duality through symmetrical framing and parallel gestures, such as the opening sequences where both characters lie in bed, restless, dreaming of escape. Uncle Charlie’s philosophy – that the world is a “foul sty” and people live blindly in it – contrasts with his niece’s youthful idealism, yet his cynicism infects her view of life by the end.

Casting was crucial to the film’s psychological depth. Joseph Cotten, best known at the time for his sympathetic roles in Citizen Kane (1941) and The Magnificent Ambersons (1942) was deliberately cast against type as the charming sociopath Uncle Charlie. His calm voice and elegance make the revelation of his crimes even more disturbing. Teresa Wright, fresh off her Oscar win for Mrs. Miniver (1942), brought innocence and intelligence to Young Charlie, avoiding the clichés of the naïve heroine. Hitchcock wanted her to embody not fragility, but moral strength — a character who could recognize evil and survive it.

The film also critiques the myth of American small-town purity. Through Wilder’s influence, the Newton household and Santa Rosa itself are painted with almost nostalgic realism: tidy houses, neighborly chatter, and Sunday dinners. But Hitchcock subverts this warmth, showing how denial and politeness allow evil to thrive unnoticed. Emma’s devotion to her brother blinds her to his nature, and the community’s reluctance to face unpleasant truths becomes complicit in maintaining appearances. Evil, Hitchcock implies, doesn’t always come from outside – it grows comfortably within the heart of the family.

The characters surrounding the two Charlies further articulate Hitchcock’s moral landscape. Emma Newton represents the sentimental blindness of family love, while her husband, played by Henry Travers, stands for the unthreatening banality of suburban normalcy. The two detectives investigating Uncle Charlie operate under cover, one of them, Jack Graham, developing a tentative affection for Young Charlie, offering her a possible path back to normal life after the trauma. Yet even that resolution feels fragile – the experience has left her unable to fully re-enter innocence.

The film was shot primarily on location in Santa Rosa, California, an unusual choice for Hitchcock, who typically favored studio control. He wanted the texture of real streets, homes, and sunlight to contrast with the sinister story underneath. This realism enhances the film’s unsettling tone – the evil doesn’t unfold in shadowy London alleys or Gothic mansions, but in tidy living rooms and cheerful front porches. Hitchcock worked closely with cinematographer Joseph A. Valentine to balance light and darkness within everyday spaces: bright daylight scenes often contain deep, creeping shadows, visually echoing the film’s theme of corruption beneath normalcy.

For music, Hitchcock turned to Dimitri Tiomkin, who incorporated The Merry Widow Waltz as a recurring motif. The tune’s cheerful rhythm becomes increasingly ironic and chilling, turning from a symbol of elegance to one of menace each time it reappears. Tiomkin’s score was one of the earliest examples of a leitmotif being used not just for identification, but as psychological commentary.

Upon its release, critics praised the film’s intelligence and restraint. It lacked the showy set pieces of Hitchcock’s later works but offered something more disturbing: the suggestion that evil hides not in exotic villains or foreign spies but in the person you love most. Its influence reverberates through later American cinema, from Blue Velvet (1986) to The Stepfather (1987) and Stoker (2013), all of which explore the terror of hidden corruption within the family home. In 1991, the Library of Congress added it to the National Film Registry, recognizing its cultural and artistic significance.

Ultimately, Shadow of a Doubt is not simply a thriller about a murderer; it is a moral study about the loss of innocence and the price of knowledge. Through the relationship between Young Charlie and her uncle, Hitchcock crafts a parable about how darkness seeps into the everyday and how acknowledging that truth forever changes the way one sees the world. By the film’s final image, the quiet town remains unspoiled on the surface, but its brightest daughter has seen the shadow beneath it.

Notes by Leandro Matos

Hitchcock’s Canadian Connection:

Beloved actor Hume Cronyn was born in London, Ontario, in 1911. After studying at McGill University and the American Academy of Dramatic Arts, he made his Broadway debut in the 1930s, quickly establishing himself as a versatile performer with impeccable timing and quiet intensity. His career spanned stage, film, and television, earning him recognition as one of Canada’s most accomplished exports to Hollywood.

Cronyn’s film career took off in the 1940s, when he signed with MGM and appeared in a number of notable films, including Alfred Hitchcock’s Shadow of a Doubt (1943), where he played the witty, crime-obsessed Herbie Hawkins. His subtle humor and natural presence made him a memorable part of one of Hitchcock’s finest thrillers. He later collaborated again with Hitchcock on Lifeboat (1944) and Saboteur (1942) (as a writer).

Throughout his life, Cronyn maintained a remarkable partnership – both personal and professional – with actress Jessica Tandy. The pair starred together in countless stage and screen projects, from The Gin Game to Cocoon, earning admiration for their enduring artistry and chemistry. Hume Cronyn’s career was recognized with multiple awards, including a Tony and an Emmy, and he remained active in the arts well into his eighties, leaving behind a legacy that bridged Hollywood and his proud Canadian roots.

SABOTEUR (1942)

Production Companies: Frank Lloyd Productions, David O. Selznick Productions. Produced by: Frank Lloyd, Jack H. Skirball. Directed by: Alfred Hitchcock. Screenplay by: Peter Viertel, Joan Harrison, Dorothy Parker. Cinematography: Joseph A. Valentine. Editing: Otto Ludwig. Music by: Frank Skinner. Release date: April 22, 1942. Running time: 109 minutes.

Cast: Priscilla Lane (Patricia Martin), Robert Cummings (Barry Kane), Otto Kruger (Charles Tobin), Alan Baxter (Freeman), Clem Bevans (Neilson), Norman Lloyd (Frank Fry).

Saboteur is a fast-paced espionage thriller employing one of Hitchcock’s signature themes – the case of “the wrong man”. Filmed as the United States was entering WWII and in production when Pearl Harbour was attacked, the film played to American audience patriotic sentiments at the time, featuring ordinary folk as the “good guys” and wealthy, elitist, facists as the “bad guys”.

When munitions worker Barry Kane (Robert Cummings) is falsely accused of setting fire to the Stuarts Aircraft Factory in Los Angeles that caused the death of his best friend, Ken Mason (uncredited), he embarks on a cross-country journey in an attempt to apprehend the real ‘saboteur’, Frank Fry (Norman Lloyd). Along the way he picks up an initially skeptical but soon supportive Patricia Martin (Priscilla Lane), who helps him in his quest for justice.

In what’s been described as his first, true American film since moving to the U.S. in the late 1930s. Rebecca (1940) and Suspicion (1941) were thematically set in England and employed mostly British actors and actresses and Foreign Correspondent (1940) had an American protagonist but was staged in the Netherlands and England), the film is assumed by many to be an Americanized version of 1935’s The 39 Steps and an obvious front-runner to the highly acclaimed 1959 thriller, North by Northwest (1959).

Under contract with David O. Selznick, the director got a taste of having to give creative control to the studio in the Hollywood system. Despite Selznick’s support, Val Lawton, Selznick’s story editor, eventually rejected the script and after being shopped around it was picked up by Universal studios.

This gave Hitchcock the opportunity to work with esteemed cinematographer Joseph Valentine, however he was not able to secure his preferred leads, Gary Cooper and Barbara Stanwyck or his runners choices, Henry Fonda and Margaret Sullivan, and ultimately had to settle on Robert Cummings and Priscilla Lane. While Hitchcock appreciated Cummings as an actor, he didn’t think he could convey Kane’s anguish with his “amusing face”. He also felt that Priscilla Lane, “wasn’t the right yoke (of leading lady) for a Hitchcock picture”.

Hitchcock also would have preferred Harry Carey to Otto Kruger as the antagonist, however Carey’s wife was adamantly against her husband, who most often played the hero in Western movies, portraying a fascist. Norman Lloyd, recommended by John Houseman and in his first ever film role, was the only cast member Hitchcock praised. Lloyd continued to act in films until 2015 and would go on to be the longest surviving of the “old Hollywood” actors, passing away at the age of 106 in 2021.

Peter Viertel, a novelist who had never written for film, was brought in to write the screenplay with help from Joan Harrison, and the script was ultimately provided with finishing touches by esteemed writer Dorothy Parker. In his famous interviews with French film Director Francois Truffaut, Hitchcock shared that “The famous Dorothy Parker collaborated on the screenplay. Some of her touches, I’m afraid, were missed altogether; they were too subtle. There was the scene of the couple who boarded a train and landed in what turned out to be the car for circus freaks. A midget opens the door, and at first the couple can’t see anyone; it’s only when they look down that they see the midget. Then there was the bearded lady with her beard done up in curlers for the night. And the row between the thin man and the midget, who was known as “the Major.” The Siamese twins who weren’t on speaking terms with each other and communicated through a third person had a funny line. One of them says, “I wish you’d tell her to do something about her insomnia. I do nothing but toss and turn all night”.

Hitchcock used extensive location footage in the film, which was unusual for Hollywood productions at the time. Radio City Music Hall is the backdrop for a clever scene in which gunshots from the film being played drown out actual gun shots and the climactic, final confrontation is set a top the Statue of Liberty (a model – not the real monument), a symbol of American solidarity and freedom. Neither of these famous scenes is accompanied by a musical score, the action itself creating tension and excitement in the audience. Hitchcock makes his trademark cameo appearance about an hour into the film, standing at a kiosk in front of Cut Rate Drugs in New York as the saboteurs’ car pulls up.

Despite a New York Times film review that described the film as “one hour and 45 minutes of almost Simon Pure melodrama from the hand of the master” and the less than star-studded cast, Saboteur was well received by audiences and made a decent profit at the box office. While not as sophisticated as some of Hitchcock’s other films, it draws you in from the opening sequence and continues at pace until the final scene.

Notes by Kathleen McLarty

Virtual Saturday Night at the Movies

Toronto Film Society will be screening Sabotage (1936) straight to your home on Saturday, February 28, 2026 at 7:30 p.m. (ET)! Directed by Alfred Hitchcock, starring Sylvia Sidney, Oscar...