The Man Who Shot Liberty Valance (1962)

Toronto Film Society presented The Man Who Shot Liberty Valance (1962) on Monday, February 21, 1983 in a double bill with The Valley of Decision as part of the Season 35 Monday Evening Film Buffs Series “B”, Programme 7.

Production Company: Paramount. Producer: Willis Goldbeck. Director: John Ford. Screenplay: Willis Goldbeck, James Warner Bellah, from the story by Dorothy M. Johnson. Photography: William Clothier. Process Photography: Farciot Edouart. Art Direction: Hal Pereira, Eddie Imazu. Set Decoration: Sam Comer, Darrel Silvers. Editor: Otho Lovering. Assistant Director: Wingate Smith. Costumes: Edith Head. Makeup: Wally Westmore. Hair Style: Nellie Manley. Musical Score: Cyril Mockridge (theme from Young Mr. Lincoln by Alfred Newman).

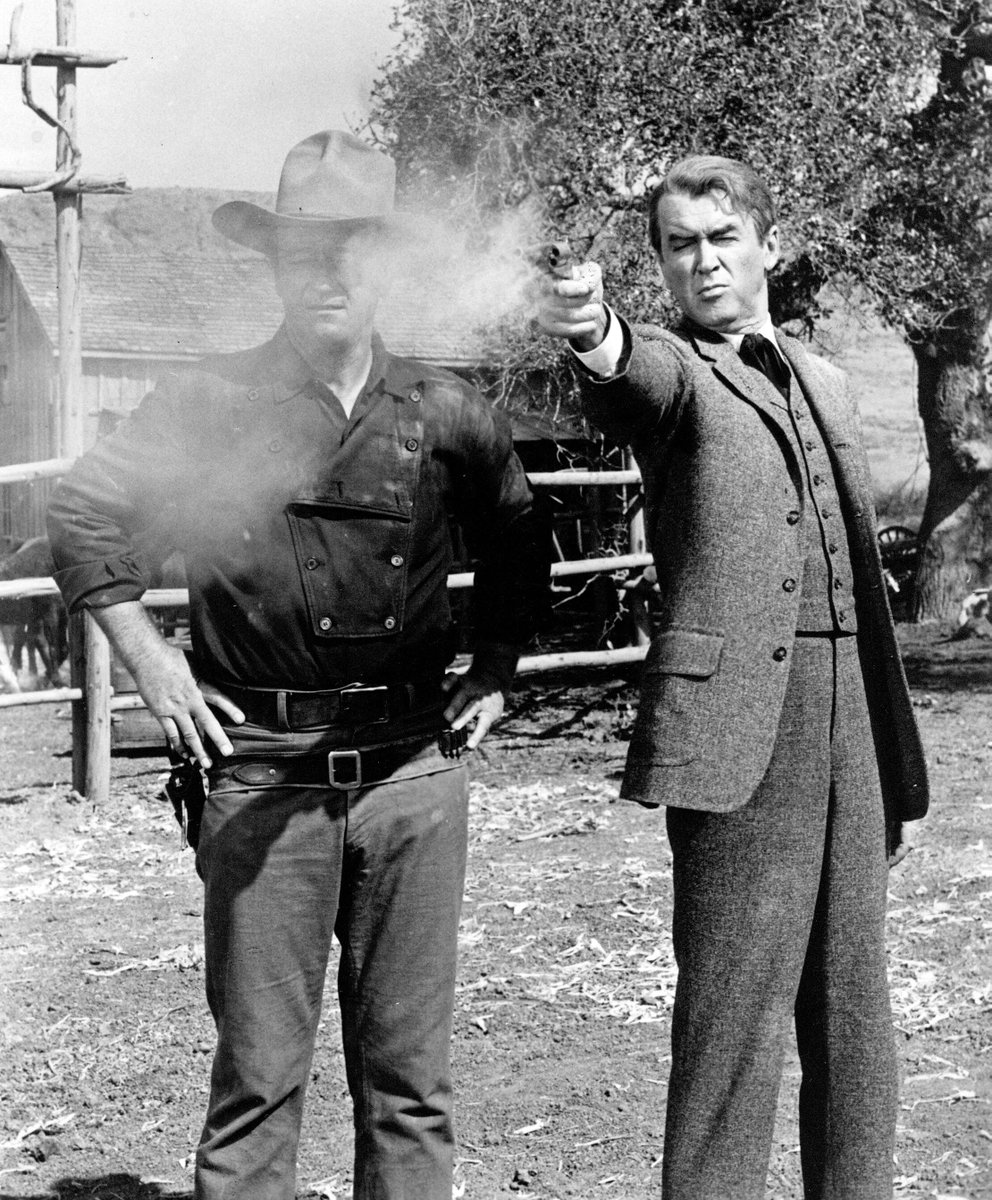

Cast: John Wayne (Tom Doniphon), James Stewart (Ransom Stoddard), Vera Miles (Hallie Stoddard), Lee Marvin (Liberty Valance), Edmond O’Brien (Dutton Peabody), Andy Devine (Link Appleyard), Ken Murray (Doc Willoughby), John Carradine (Starbuckle), Jeannette Nolan (Nora Ericson), John Qualen (Peter Ericson), Willis Bouchey (Jason Tully), Carleton Young (Maxwell Scott), Woody Strode (Pompey), Denver Pyle (Amos Caruthers), Strother Martin (Floyd), Lee Van Cleef (Reese), Robert Simon (Handy Strong), O.Z. Whitehead (Ben Carruthers), Paul Birch (Mayor Winder), Joseph Hoover (Hasbrouck), Jack Pennick (Barman), Anna Lee (Passenger).

The Man Who Shot Liberty Valance is a political Western, a psychological murder mystery and John Ford’s confrontation of the past–personal, professional and historical. The title itself suggests a multiplicity of functions. “The man who” marks the traditional peroration of American nominating conventions, and has figured in the titles of more than fifty American films. In addition to evoking past time, “shot” may imply a duel, a murder or an assassination. “Liberty Valance” suggests an element of symbolic ambiguity. This is all a priori. After the film has unfolded, the title is reconstituted as bitter irony. The man who apparently shot Liberty Valance is not the man who really shot Liberty Valance. Appearance and reality? Legend and fact? There is that and more, athough it takes at least two viewings of the film to confirm Ford’s intentions and at least a minimal awareness of his career to detect the reverberations of his personality.

The opening sequences are edited with the familiar incisiveness of a director who cuts in the camera and hence in the mind. James Stewart and Vera Miles descend from a train which has barely puffed its way into the twentieth century. Their powdered make-up suggests that all the meaningful action of their lives is past. The town is too placid, the flow of movement too stately, and the sunlight bleaches the screen with an intimation of impending nostalgia. An incredibly aged Andy Devine is framed against a slightly tilted building which is too high and too full constructed to accommodate the violent expectations of the genre. The remarkable austerity of the production is immediately evident. The absence of extras and the lack of a persuasive atmosphere forces the spectator to concentrate on the archetypes of the characters. Ford is well past the stage of the reconstructed documentaries (My Darling Clementine) and the visually expressive epics (She Wore a Yellow Ribbon). His poetry has been stripped of the poetic touches which once fluttered actross the meanings and feelings of his art. Discarding all the surface artifices of realism, Ford runs the risk of seeming as lumberingly didactic as the late Renoir of Le Dejeuner sur l’herbe and the late Dreyer of Gertrud. Ford’s brush strokes of characterization seem broader than ever….

It is hardly surprising that the plot essence of the flashback is less important than the evocations of its characters. Whatever one thinks of auteurism, the individual films of John Ford are inextricably linked in an awesome network of meanings and associations. When we realize that the man in the coffin is John Wayne, the John Wayne of Stagecoach, The Long Voyage Home, They Were Expendable, Fort Apache, She Wore A Yellow Ribbon, Rio Grande, Three Godfathers, The Quiet Man, The Searchers and Wings of Eagles, the one-film-at-a-timereviewer’s contention that Wayne is a bit old for an action plot becomes absurdly superficial. The Man Who Shot Liberty Valance can never be fully appreciated except as a memory film, the last of its kind, perhaps, from one of the screen’s old masters….

Although The Man Who Shot Liberty Valance achieves greatness as a unified work of art with the emotional and intellectual resonances of a personal testament, there are enough shoulder-nudging “beauties” in the direction to impress the most fastidious seekers of “mere” technique. There is one sequence, for example, in which Edmond O’Brien addresses his own shadow as a forensic foreshadowing of a brutal beating he is about to receive, which might serve as a model of how the cinema can be imaginatively expressive without lapsing into impersonal expressionism. The vital thrust of Ford’s actors within the bursting frames of his shot sequences demonstrates that life need not be devoid of form, and that form need not be gained at the expense of vitality. The Man Who Shot Liberty Valance must be ranked along with Lola Montes and The Magnificent Ambersons as one of the enduring masterpieces of that cinema which has chosen to focus on the mystical processes of time.

The John Ford Mystery by Andrew Sarris, Secker & Warburg, 1976

Leave a Reply