Winchester 73 (1950)

Toronto Film Society presented Winchester 73 (1950) on Sunday, January 10, 1988 in a double bill with Trail of the Vigilantes as part of the Season 40 Sunday Afternoon Film Buffs Series “A”, Programme 6.

Production Company: Universal. Producer: Aaron Rosenberg. Director: Anthony Mann. Screenplay: Robert L. Richards, Borden Chase, from the story by Stuart N. Lake. Photography: William Daniels. Music: Joseph Gershenson. Editor: Edward Curtiss. Art Direction: Bernard Herzbrun, Nathan Juran. Costumes: Yvonne Wood.

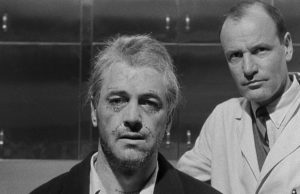

Cast: James Stewart (Lin McAdam), Shelley Winters (Lola Manners), Dan Duryea (Waco Johnny Dean the Kansas Kid), Stephen McNally (Dutch Henry Brown), Millard Mitchell (Johnny “High Spade” Williams), Charles Drake (Steve Miller), John McIntire (Joe Lamont), Will Geer (Wyatt Earp), Jay C. Flippen (Sergeant Wilkes), Rock Hudson (Young Bull), John Alexander (Jack Rider), Steve Brodie (Wesley), James Millican (Wheeler), Abner Biberman (Latigo Means), Anthony Curtis (Doan), James Best (Crater), Gregg Martell (Mossman).

This second Western from Universal is clearly among its big-budget products even though it was not shot in colour. Its black and white photography (along with the psychotic obsession of its hero) links the film to some of the earlier low-budget film noir productions of its director, Anthony Mann. The film was originally conceived as a project by and for that master of the genre, Fritz Lang. But when Lang walked away from his own incipient script, James Stewart, who had seen Mann’s Robert Taylor Western at MGM, The Devil’s Doorway, recommended Mann as a replacement. This would be the first of eight successful collaborations between Stewart and Mann. It is safe to say that Anthony Mann exploited the James Stewart persona in his own way just as successfully as did Frank Capra and Alfred Hitchcock in their more famous films.

At the time of its release, most of the reviewers, including Bosley Crowther, remained blind to the psychotic overtones of the film. Some current historians still maintain that it is merely a traditional archetypal Western, but there are others who argue that this film, along with Henry King’s The Gunfighter of the same year, opened the door to the “adult” Western classics which would follow: Zinnemann’s High Noon, George Stevens’ Shane and the films of Budd Boetticher, Don Siegel, Samuel Fuller and Nicholas Ray. The film is, to a certain extent, structured episodically around the peregrinations of the rifle as it is transferred from owner to owner. In this way, this Western can be oddly grouped with such films as Tales of Manhattan (1942) and The Yellow Rolls Royce (1965) which are silmilarily structured around the unexpected itinerary of material possessions. At the same time, Winchester 73 can be seen as an epic quest in the grand tradition of Homer’s Odyssey. And in biblical terms, the film can be read as a moral tale in which man must purge his dark obsessions in the brutal wilderness in order to enter a promised land.

Winchester 73 was an immense box-office success–to the great delight of James Stewart, who had unusually (for the time) chosen to take a percentage of the profits in lieu of salary. His first Western since Destry, this film launched him as a major star in the Western genre in the same year s his very different Oscar-nominated performance in Harvey. The entire cast of this film reads like a Who’s Who of the Universal supporting players of 1950: Shelley Winters was still in her sex-pot stage; Dan Duryea delivers another of his classic mean and sneering performances; and it is fascinating to see Tony Curtis and Rock Hudson as the fledgling performers that they would quickly cease to be.

Notes by Cam Tolton

Leave a Reply