Mother (1926)

By Toronto Film Society on December 29, 2016

Toronto Film Society presented Mother (1926) on Monday, April 16, 1962 as part of the Season 14 Monday Evening Silent Film Series, Programme 6.

The Editing Principle, and All That

The Bridge (Netherlands 1928). Directed by Joris Ivens. “An acute visual analysis of the functional movements of a railroad bridge near Rotterdam, which is raised and lowered to permit the river traffic to pass” – by the maker of Rain, show last season.

Mother (USSR 1926), Directed by V.I. Pudovkin. Scenario: N.A. Zharki, based on a novel by Maxim Gorki. Camera: A.N. Golovnia. Design: S.V. Koslovski.

Cast: Vera Baranovskaia (The Mother); A. Chistiakov (The Father); Nikolai Batalov (Pavel, the Son); V.I. Pudovkin (Bespectacled “Police Rat”).

Preparation and Production

There have been three Russian films of this Groki novel. Of the first (1920) little seems to be known; Mark Donskoi (of the Gorki Trilogy fame) made a fine sound version in 1955 that treated the material somewhat differently.

In preparing the 1926 version, Zharki was encouraged to treat the novel freely, making his scenario a transformation of the original rather than an “adaptation”. Drawing on memoirs of the revolutionary movement of 1905 and 1906, he created a script that “purified and simplified Gorki’s looser novel to an almost classic structure”. The character of the father, for example, who illuminates the film both dramatically and socially, is not in the novel. The dramatization of the trial scene was modelled on the trial in Tolstoi’s Resurrection. Gorki was not happy with the news that the picture was only generally related to his work. He asked to see the finished film. Although Soviet films were forbidden in Italy, a copy of Mother was admitted to Capri for a private showing to Gorki. Apparently he gave his approval reluctantly. Later he said: “Men of letters should take a more active part in the work of the cinema. We literary men should make the scenarios: that is our business”.

In the scenario, Zharki and Pudovkin consciously established a sonato outline: first and second reels–allegro (saloon, home, factory, strike, chase); third reel–a funereal adagio (dead father, scene between mother and son); fourth and fifth reels–allegro (police, search, betrayal, arrest, trial, prison); sixth and seventh–a mounting, furious presto (spring thaw, demonstration, prison revolt, ice-break, massacre, death of son and mother). This early consideration for tempo is a contributing factor to the notable rhythmic harmony of Mother.

Some remarks from Pudovkin on his film-making theories at this time: “The greatest artists, those technicians who feel the film most acutely, deepen their work with details. To do this they discard the general aspect of the image ,and the points of interval that are the inevitable concomitant of every natural event–in the disappearance of the general, obvious outline and the appearance on the screen of some deeply hidden detail, filmic representation attains the highest point of its power of external expression. In composing the shots we aimed to fill them efficiently with the required action. Whenever we noticed some dead place at the edge of a shot, we would eliminate it, to have nothing useless or superfluous in the composition.”

And from the cameraman, Golovnia: “In showing a developing situation in a film, one usually alters the psychological image of the protagonist. For example, the downtrodden woman in Mother was transformed into a heroine, willing to sacrifice herself. On the path that the actor must take to accomplish this, he must be accompanied by the cameraman. We would film her initial image of an oppressed, humiliated woman from slightly above, with harsh, flat lighting and miserly, dry compositions. Her final image, of a heroine filled with titanic strength, would be filmed from below, no longer concentrating on the texture of her face, but giving the whole head and face its maximum power”.

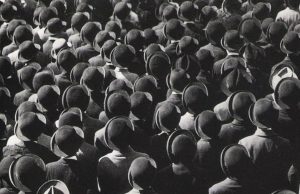

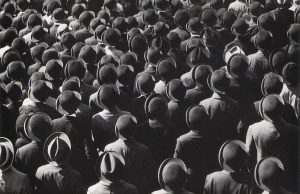

Production Incidents: It is said that during the filming of the hero’s escape across the broken ice, both the actor Batalov and the double hired for the job refused to risk their lives on the ice; so the assistant director, Mikhail Doller, donned Pavel’s costume and performed the feat himself. Then, for the scene of the May Day demonstration being run down by the mounted police, Doller recruited 700 factory workers (to eke out the studio–permitted 200 paid extras); and when these proved shy about running along the street, both Doller and Pudovkin led the crowd, racing ahead of the horses. When Pudovkin was unsatisfied with the effect of panic produced by his volunteers, he created a real one by ordering an unannounced change of direction by the horses–with both him and his ideal assistant running in the midst of the crowd.

The Film

Eisenstein has said that in Pudovkin’s films” the spectator’s attention is not concentrated on the development of the plot, but on the psychic change undergone by some individual under the influence of the social process. He puts real living men in the centre of his work. His films act directly through their emotional power”. Mother, his most noted film and considered by many among the cinema’s finest works, is the best example of this. Vera Baranovskaia interprets the mother’s role with prodigious humanity. Thanks to her and to the meticulous art of Pudovkin, it is this humanity that strikes one, more than the social propaganda.

In Mother was seen the scientific method of the decomposition of a scene into its ingredients, the choice of the most powerful and suggestive, and the rebuilding of the scene by filmic representation on the screen. In this respect one may cite the sequence of suspense at the factory gate; the gradual assembly of the workers; the feeling of uncertainty as to what was to happen. This was the result of an extraordinarily clever construction of shots and of camera set-ups in order to achieve one highly emotional effect. It may perhaps appear the simplest of methods, the basis of all filmic representation; but it needs the creative skill of a Pudovkin to extract such dramatic force from a scene. One recalls also the falling of the clock; the discovery of the hidden firearms under the floorboards; the trial, with the judges drawing horses on their blotting pads; the coming of spring; the escape from the prison; and the final crescendo ending of the cavalry charge. The primary weapon in the building of scenes is Pudovkin’s use of reference by cross-cutting. In Mother there was the constant inclusion of landscape, of nature, noticeable in every sequence. It was not symbolic, but the sheer use of imagery to reinforce drama–the shots of empty landscape in the opening; the trees and the lake cut in with the boy in prison; the breaking ice, rising by cross-cutting to a climax in reference to the cavalry charge.

Throughout Mother, unusually unified in graphic style as it is, the image often seems to have been scientifically stripped of every distracton, forcing the small, apparently involuntary gesture or flicker of an eye upon you, and in this Pudovkin has the collaboration of Golovnia and of the equally sensitive designer, Koslovski. It was Kuleshov who first taught Pudovkin the dramatic value of such cinematic pointing, though Pudovkin’s practice on Mechanics of the Brain must have reinforced the lesson. By comparison with these stripped images, their many sources appear almost cluttered or ornamental–Velasquez’ ‘Bollo’ that brought the famous camera-angle of the monumental policeman into being; van Gogh’s ‘Prison Couryard’ (after Dore), inspiration for the scene of the prison exercise hour; the carefully composed realism of Degas, the haggard blue-period paintings of Picasso and the prints of Kathe Kollwitz, that all contributed to the graphic presentation of the mother; Rouault’s three ‘Judges’ that helped to characterize Pudovkin’s three judges.

More important than any individual compositions in Mother is its continuation of the Griffith-Eisenstein tradition of camera as active observer rather than mere spectator. The film carried a conviction as though an extraordinary cameraman had been present at actual events. Its editing is the logical outcome of the disjunctive cutting introduced by Edwin S. Porter, enlarged by D.W. Griffith and others, and analyzed by Kuleshov. Although in direct theoretic opposition to Eisenstein’s shock montage, Pudovkin used a linkage method beyond Kuleshov’s ‘brick-by-brick’ construction.

But the expert cutting on human manovement of Mother has been more widely absorbed into general film technique than its more abstract cutting propositions. The photography of the actors is especially emotional in effect. Pudovkin has told how he established personal relationships with each actor in his films, a method that, particularly in Mother, renders them intimate to the spectator, helping to make this the most lyrical and immediate film of this first rich period of Soviet films.

References: Jay Leyda: Kino, a History of the Russian and Soviet Film; Paul Rotha: The Film Till Now; Bardeche and Brasillach: History of the Film.

P.S. It may be of interest that Nikolai Batalov (Pavel) was the uncle of Alexei Batalov, who played the same role in Donskoi’s remake, as well as the heroes of The Cranes are Flying and The Lady with the Little Dog.

You may also like...

-

News

Frances Blau

Toronto Film Society | February 27, 2024On Monday, February 26th, 2024, Toronto Film Society lost longtime friend, supporter, and board member Frances Blau. Known for her sense of humour, her love of film, her generosity,...

-

Special Events

Monday Evening Film Noir Double Bill at the Paradise Theatre

Toronto Film Society | July 8, 2024The Toronto Film Society presents a film-noir double feature at one low price! The Window (1949) in a double bill with Black Angel (1946) at the Paradise Theatre on Monday, August...

Programming

Virtual Saturday Night at the Movies

Toronto Film Society | July 20, 2024Toronto Film Society is back in the theatre! However, we’re still pleased to continue to bring you films straight to your home! Beginning Season 73 until now we have...

4-

Toronto Film Society | July 8, 2024

Toronto Film Society | July 8, 2024

Monday Evening Film Noir Double Bill at the Paradise Theatre

-

Toronto Film Society | November 6, 2022

Toronto Film Society | November 6, 2022

-

Toronto Film Society | August 1, 2023

Toronto Film Society | August 1, 2023

Donate to Toronto Film Society – We’re now a Registered Charity!

-

Copyright © 2017 Toronto Film Society.

Leave a Reply