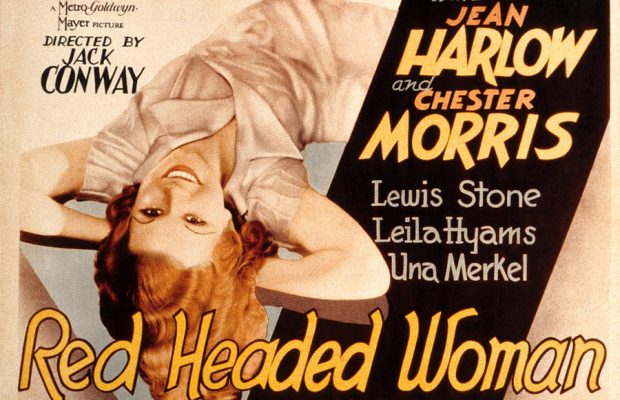

Red-Headed Woman (1932)

Toronto Film Society presented Red-Headed Woman (1932) on Sunday, May 19, 2019 in a double bill with Wonder Bar as part of the Season 71 Sunday Afternoon Special Screening #11.

Production Company: Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer. Director: Jack Conway. Producers: Albert Lewin, Irving Thalberg. Screenplay: Anita Loos (Uncredited Contributors: Felix E. Feist, F. Scott Fitzgerald, Bess Meredyth, C. Gardner Sullivan), based on the book by Katharine Brush. Cinematography: Harold Rosson. Film Editing: Blanche Sewell. Art Director: Cedric Gibbons. Gowns: Adrian. Release Date: June 25, 1932.

Cast: Jean Harlow (Lil Andrews), Chester Morris (Bill Legendre Jr.), Lewis Stone (William Legendre Sr.), Leila Hyams (Irene), Una Merkel (Sally), Henry Stephenson (Gaerste), May Robson (Aunt Jane), Charles Boyer (Albert), Harvey Clark (Uncle Fred).

This is one of the best-known, possibly one of the top ten favourite pre-Code film that has all the elements of what makes this genre such a delight. A sexy, scheming, manipulative, narcissistic, unrelentless woman goes after what she wants and doesn’t let up or let anything—like, say, a man’s wife—stop her from getting her way. And when she does achieve her goal, goes on to be very, very bad and still gets away with everything.

Anita Loos, who started her very long writing career in Hollywood in 1912 at the age of 23, is considered most famous for her stories of Lorelei in “Gentlemen Prefer Blondes” which was first published in November 1925. In 1932, she was married to actor/director/writer John Emerson and when they were offered to write films for MGM, Hollywood’s most prestigious studio run by production head Irving Thalberg, Emerson refused. So Anita took the $1,000-a-week job solo. Her first project was tonight’s film, taking it over from F. Scott Fitzgerald who was having a difficult and unsuccessful time adapting Katherine Brush’s novel. Red-Headed Woman, completed in May 1932, was the smash hit that established Jean Harlow as a star and made Loos once again one of the hottest screenwriters in town. MGM producer Samuel Marx had this to say about Anita: “Loos was a very valuable asset for MGM, because the studio had so many femmes fatales—Garbo, Crawford, Shearer and Harlow—that we were always on the lookout for ‘shady lady’ stories. But they were problematic because of the censorship code. Anita, however, could be counted on to supply the delicate double entendre, the telling innuendo. Whenever we had a Jean Harlow picture on the agenda, we always thought of Anita first.”

It’s been a couple of years since I last saw this picture and I hope you are looking as forward to viewing as I am. It’s a real treat!

Introduction by Caren Feldman

What the critics said about Red-Headed Woman:

All this viciousness, and a dose of gratuitous snideness to boot, is transferred to the screen version of Red-Headed Woman, which was presented to a generously admiring audience yesterday at the Capitol as a fast and at times hilarious satirical comedy…. Whether the pleasure of the first audience of the picture was derived from appreciation of Miss Harlow’s satirical characterization of a feminine type, or from the belief that she is the hottest number since Helen of Troy started her career of firing topless towers, was difficult to determine. That it enjoyed the film vastly was patent.

New York Herald Tribune, Lucius Beebe

Red-Headed Woman—red hot cinema! The Capitol’s current offering is lurid and laugh-enticing in the bigger and better box-office manner. And the ex-platinum Jean Harlow now sparkles as a titian siren, her emoting improved immeasurably along with the change in the shade of her tresses. Svelte, slender, and seductive, Harlow gives a splendid performance, making the picture more a character study of a woman who trades on her physical charms than a narrative romance.

New York Daily News, Irene Thirer

Filled with laughs and loaded with dynamite, it exposes the males as chumps and convincingly describes what the tired businessman likes. The answer is Harlow. This shapely beauty gives a performance which will amaze you, out-Bowing the famed Bow as an exponent of elemental lure and crude man-baiting technique.

New York Daily Mirror, Bland Johaneson

The Films of Jean Harlow, edited by Michael Conway and Mark Ricci (1965)

There is every indication that the MPPDA (Motion Picture Producers and Distributors of America) was aware of the nature and extent of the criticisms being directed at Hollywood. For example, writing of the film Red-Headed Woman in 1932, an industry censor compared the figure of the gold digger and that of the gangster, and noted that in each case complaints centered upon the problem of glamour: “There is a striking similarity between the treatment of this character and the earlier treatment of the gangster character…. Because he was the central figure, because he achieved power and money and a certain notoriety, our critics claimed that an inevitable attractiveness resulted. And that was what they objected to in gangster pictures. They said we killed him off but that we made him glamorous before we shot him. This is what you are apt to be charged with in the case. While the Red-Headed Woman is a common little creature from over the tracks who steals other women’s husbands and uses her sex attractiveness to do it, she is the central figure and it will be contended that a certain glamour surrounds her.”

—

Many gold-digger films, including Bed of Roses, Red-Headed Woman, Baby Face, The Greeks Had a Word for Them, She Done Him Wrong, and I’m No Angel, would probably be classified as comedies by most film critics, and hence at the perimeters of the fallen woman genre, properly conceived as a subset of melodrama. Industry censors, however, classified comedies like The Greeks Had a Word for Them as “sex pictures,” in tandem with films like Madame X, which we would consider pure melodrama. Indeed, they gave much attention to the ways in which comedy could be used for strategic purposes, as a means of justifying otherwise unacceptable material. These films are thus interesting precisely because they crossed the boundary between comedy and melodrama. Their comedy frequently derives from a parodic inversion of genre conventions. They played havoc with the traditional characterization of the fallen woman and the corresponding notions of innate feminine passivity and innocence.

I propose to consider the process of self-regulation in some detail in the case of Baby Face. The film is of interest because it is clearly a limit case, one which provoked a great deal of comment both inside and outside the industry. Made by Warners in 1933, it was banned in Switzerland, Australia, three Canadian provinces, and in the United States in Virginia, Ohio, and initially New York (where it was later released). It was widely criticized in the popular press and was one of the films listed by Martin Quigley as particularly offensive to the Catholic Legion of Decency. The Studio Relations Committee’s failure to protect the industry on this score was not the result of a simple oversight. In the first review of the script, James Wingate, who was working for the industry at this time, warned the studio that the story was likely to run into trouble: “It is exceedingly difficult to get by with the type of story which portrays a woman who, by means of her sex, rises to a position of prominence and luxury.” He even cautioned that a film with a similar theme (probably MGM’s Red-Headed Woman) had been banned in several Canadian provinces. Thus, the Studio Relations Committee’s difficulty with Baby Face did not stem from a difficulty in anticipating the responses of external agencies, but rather lay in the form of the revision enacted according to the Studio Relations Committee’s standard operating policy and procedure.

—

…Thus, it became even more difficult for industry censors to negate the image of the calculating, aggressive woman, or reinstate a normative view of the relations between the sexes. At the conclusion of Red-Headed Woman, for example, the heroine is rejected by her wealthy husband, who has been reconciled with his virtuous former wife. Town gossips predict the redhead will end “in the gutter,” but this punishment does not occur. Instead a tag ending shows her in Paris, in the company of a rich old marquis and a handsome young chauffeur (played by Charles Boyer).

The Wages of Sin: Censorship and the Fallen Woman Film, 1928-1942 by Lea Jacobs (1991)

Her miracle year was 1932. In February, The Beast of the City opened, and suddenly Harlow could act. She played another gangland moll, but there was something natural and relaxed about her quality—and sympathetic, too. On the strength of her performance, MGM bought out her contract. The producer Paul Bern had the insight that Harlow’s métier was comedy, and she was cast in Red-Headed Woman (1932). Again she was a sex vulture, but this time she was a lampoon of one. She was Lil, a gold-digging secretary who sets out to seduce her boss and ruin his marriage. When she meets a richer, older man, she seduces him, too, and behind his back, carries on with the old fellow’s chauffeur (Charles Boyer). “Sex! Sex! Sex!” a local censor from Atlanta complained. “The picture just reeks with it until one is positively nauseated.” Lil’s wheels are always turning. When the boss (Chester Morris), enraged by her efforts to break up his marriage, slaps her, Harlow’s face lights up. “Do it again! I like it! Do it again!” she exclaims. She is unstoppable, a man’s nightmare presented in comic terms by a woman screenwriter (Anita Loos) and acted by a sharp comedienne. Red-Headed Woman, in addition to proving that Harlow was funny, revealed her as a valiant performer. In this and subsequent films, Harlow throws herself into scenes, unguarded, in a volatile free-fall.

Complicated Women by Mick LaSalle (2000)

Notes Compiled by Caren Feldman

Leave a Reply