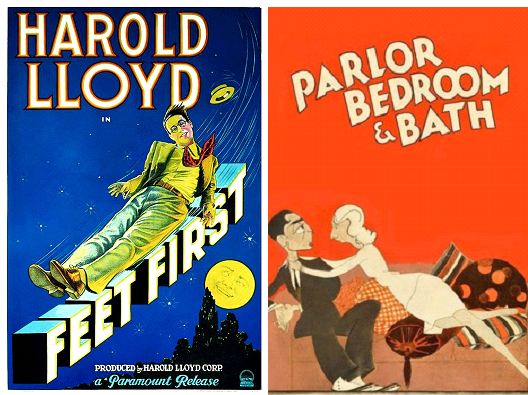

Feet First (1930) and Parlor, Bedroom and Bath (1931)

By Toronto Film Society on May 22, 2020

Toronto Film Society presented Feet First (1930) on Sunday, March 3, 1985 in a double bill with Bedroom and Bath (1931) as part of the Season 37 Sunday Afternoon Film Buffs Series “A”, Programme 9.

Feet First (1930)

Production Company: Paramount. Director: Clyde Bruckman. Assistant Directors: Gaylor Lloyd and Mal de Lay. Scenario: Felxi Adler and Lex Neal, dialogue by Paul Gerard Smith, story by John Grey, Al Cohn and Clyde Bruckman. Photographers: Walter Lundlin and Henry Kohler. Editor: Bernard Burton. Production Manager: John L. Murphy. Sound Technicians: Cecil Bardwell and William R. Fox. Art Director: Liell K. Vedder. Technical Director: William MacDonald.

Cast: Harold Lloyd (Harold Horne), Barbara Kent (Barbara), Robert McWade (John Quicy Tanner), Lillianne Leighton (Mrs. Tanner), Henry Hall (Endicott), Alec B. Francis (Old Timer, Mr. Carson), Noah Young (Ship’s Officer), Arthur Housman (Drunken Clubman), Willie Best, “Sleep ‘n’ Eat” (Charcoal, a janitor).

Parlor, Bedroom and Bath (1931)

Production Company: M.G.M. Director: Edward Sedgwick. Adaption: Richard Schayer, Robert E. Hopkins, from the play by Charlee W. Bell and Mark Swan. Photography: Leonard Smith. Editor: William Le Vanway. Recording Engineer: Karl Zint.

Cast: Buster Keaton (Reginald Irving), Charlotte Greenwood (Polly Hathaway), Reginald Denny (Jeffery Haywood), Cliff Edwards (Bellhop), Dorothy Christy (Angelica Embrey), Joan Peers (Nita Leslie), Sally Eilers (Virginia Embrey), Natalie Moorhead (Leila Crofton), Edward Brophy (Dectective), Walter Merrill (Frederick Leslie), Sidney Bracy (Butler).

In the silent era, Hollywood’s trinity of screen comedians were Chaplin, Lloyd and Keaton. Each of these men had their own style and techniques. Lloyd was forever playing the bespectacled, straw-hatted, bound-to-succeed American boy, garbed in a bargain-basement suit. He was the average everyday man confronted with life’s struggle in the never ending pursuit of happiness. Within the framework of the deceptively shy, hesitantly smiling go-getter, Lloyd devised some of the most thrilling sight gags put on film. His character was always coping with a less than friendly world and combating the recurring animosity of inanimate objects. But no matter what, his goals were clear–he was seeking career success and the affection of the girl of his dreams.

Harold Lloyd’s screen persona was much closer to his offscreen reality than either Chaplin’s or Keaton’s. Keaton was the incompetent bungler, the physical magician; the conflict between the two opposites became an essential part of every film. Lloyd, however, adopted a character as close to himself as possible and then revealed nothing. He consistently cut us off at the surface.

When sound arrived, both Lloyd and Keaton were propelled into the world of sound; only Chaplin was a holdout. Both comedians had their own problems. Although Lloyd’s films never lost money, he had a lot of trouble adjusting to the sound era, making only seven films before retirement. During the 20’s, Lloyd’s films often outdrew at the box office the films of Chaplin and Keaton. In addition to his skill as a comedian, Lloyd had another important asset–his athletic prowess. Lloyd’s career, unlike Keaton’s, was a gradual evolution. And, unlike Keaton and Chaplin, Lloyd wasn’t a natural comedian. His rivals came to film the way of vaudeville and carried their knowledge of physical comedy and sense of professionalism with them.

Lloyd’s fascination with height was evident in the earlier Never Weaken, in which a steel girder, being placed on another skyscraper opposite his office, swings into the window lifting Lloyd and his chair into space. Later, in the sound feature Feet First, he repeated the climbing stunt. All of Lloyd’s thrill gags were carefully blueprinted, developed, executed and heightened by expert editing. Like Chaplin, Lloyd would labour over his films for months on end, constantly working to improve sequences and build a stronger plot structure for the gags.

Feet First was Lloyd’s second sound film, and contained less talk and more visual gags than his first sound feature, Welcome Danger, in an attempt to resurrect the thrill factor that had contributed so heavily to the success of his past films, especially Safety First. Feet First permanently established and the public’s perception of Lloyd’s talking character.

Buster Keaton was the man who entered a room, picked up a can of paint and a brush and after painting a hook on a wall, hung up his hat on the hook. He was the man who sat prisoner on a ship, looking at the world through a porthole, only to have his captor enter the cabin and remove the porthole. (The name Buster was given by Harry Houdini). Keaton is a recent rediscovery by many. An accomplished actor unlike other great comedians of his day, he developed a wide range of different characters. In The Boat he is a husband and father; in College and Steamboat Bill Jr. he is a college boy. In several of his films he plays a millionaire; in still others, he is a fugitive bum. He gave each character its own, self-centred validity, and yet in the end they all fused into one divine figure and became Buster.

Although Harold Lloyd was more popular than Keaton in their silent days, Keaton, today, is recognized by critics and the public as the better of the two. There were many facets in Keaton’s off-stage personality that affected his films. Since his dunce-clown was uncannily convincing, some people, especially producers, thought the actor might have the same simple uncomplicated personality. But inside Buster was a bright man, a bundle of energy, innovation and sensitivity. Keaton at many times would not show his emotions and would clasp a ‘mask’ tightly over his true emotions.

Keaton is best characterized as The Great Stone Face, yet he had the most expressive face in films. Asked why he never smiled, he once answered, “I had other ways of showing I was happy.” A slow blink could express a climax of joy, and when at the end of The Three Ages he gets the girl and celebrates by throwing his hat into the air, his ecstasy is explosive.

No analysis of Keaton’s personality can be discussed without his attitude towards acrobatic gags. He was surely a superior comic in this activity and was daring in executing some of the most spectacular comic tricks of all time. In early days he padded himself and doubled for Fatty Arbuckle, executing falls from trains and so forth. Many thought that he was crazy, especially in Steamboat Bill Jr., with only a 3 inch clearance around him to have a 2 ton house front collapse over him like a giant fly-swatter.

Unfortunately, Keaton’s artistic integrity was not linked with a strong business sense. Chaplin and Lloyd had a combination of these qualities that helped them retain control of their productions and kept the merit of their films on a high level until nearly the end of their careers. Late in the 20’s Keaton’s films began to wane in quality when he lost control of the total creative process.

In the late 20’s Keaton gave up his production company and moved to M.G.M. in what he eventually considered to be the worst mistake of his career. He made his first feature for them called The Cameraman. The films he started to do did well but Keaton wanted to develop his own material. The studio felt that the material he wanted to develop was dated and that slapstick was undignified and unsuited to the modern sound picture. Irving Thalberg had bought a story for Buster and had assigned comedienne Charlotte Greenwood as leading lady. It was the 1917 Broadway hit Parlor, Bedroom and Bath. Buster took it well but with reservations. He told the studio that it was not his type of picture but put his all into it. A lot of critics, American and foreign alike, questioned M.G.M.’s judgement. Most of the film was made on location in Keaton’s Beverly Hills home where he also did the foreign versions of the same picture (a German version called Casanova wieder Willen and a French version Buster so marie). Some of the shots of his fine place add something that the picture would have lacked if it had been shot on a studio sound-stage. Keaton wanted authentic locales, costumes and props in the execution of his stories.

Both Lloyd and Keaton had great admiration for each other. Keaton once said of Lloyd that he found him a great picture man, “an experimenter”. Lloyd had also admired Keaton’s ability to spin an excellent comic tale. Both were most anxious to create the best stories for their characters. The story always took priority, with the actor next.

Notes by Fred Cohen

You may also like...

-

News

Frances Blau

Toronto Film Society | February 27, 2024On Monday, February 26th, 2024, Toronto Film Society lost longtime friend, supporter, and board member Frances Blau. Known for her sense of humour, her love of film, her generosity,...

-

Special Events

Monday Evening Film Noir Double Bill at the Paradise Theatre

Toronto Film Society | July 8, 2024The Toronto Film Society presents a film-noir double feature at one low price! The Window (1949) in a double bill with Black Angel (1946) at the Paradise Theatre on Monday, August...

Programming

Virtual Saturday Night at the Movies

Toronto Film Society | July 20, 2024Toronto Film Society is back in the theatre! However, we’re still pleased to continue to bring you films straight to your home! Beginning Season 73 until now we have...

4-

Toronto Film Society | July 8, 2024

Toronto Film Society | July 8, 2024

Monday Evening Film Noir Double Bill at the Paradise Theatre

-

Toronto Film Society | November 6, 2022

Toronto Film Society | November 6, 2022

-

Toronto Film Society | August 1, 2023

Toronto Film Society | August 1, 2023

Donate to Toronto Film Society – We’re now a Registered Charity!

-

Copyright © 2017 Toronto Film Society.

Leave a Reply