Applause (1929)

Toronto Film Society presented Applause (1929) on Sunday, February 28, 1988 in a double bill with Dance, Girl, Dance as part of the Season 40 Sunday Afternoon Film Buffs Series “A”, Programme 9.

Production Company: Paramount. Producer: Monta Bell. Director: Rouben Mamoulian. Script: Garrett Ford, from the novel by Beth Brown. Photography: George Folsey. Editor: John Bassler.

Cast: Helen Morgan (Kitty Darling), Joan Peers (April Darling), Fuller Mellish Jr. (Hitch Nelson), Henry Wadsworth (Tony), Jack Cameron (Joe King), Dorothy Cumming (Mother Superior).

Today’s two films take us into the world of burlesque. But they do so by a circuitous route. While Applause takes us on a detour into a convent, Dance, Girl, Dance keeps leading us back into the world of classical ballet! But the lingering after-taste from both films is that of a raunchy, sleazy atmosphere of talentless chorines and lippy male oglers. Applause in particular was praised by its 1929 critics for its authentic presentation of back-stage burlesque.

Both films have enjoyed a renewed interest in recent years–and for quite different reasons. In the case of Applause, recent film historians have been quick to recognize that this is one of the first sound films to overcome some of the problems that the introduction of sound recording brought to the Hollywood studios. At the time, studios were agonizing over ways to record sound on the set without picking up the whir of the cameras or the heartbeat of the heroine (as we see hilariously illustrated in Singin’ In The Rain). Director Rouben Mamoulian solved the problem by filming many segments (such as some of the convent footage) with a moving camera as though they were silent, and adding the sound later through post-synchronization. Mamoulian also devised for this film the brand new concept of using two microphones to record the voices of two different characters who are speaking at different volumes, and blending them later. Apparently, this idea occurred to him while filming the scene where the mother sings a lullaby (a song from her show) to her daughter who is saying her prayers. But there are other moments where the primitiveness of the sound recording is apparent. For instance, in many shots, the audience can enjoy speculating in what stage prop the microphone is hidden. In the trunk? Behind some ever-present photographs? In the napkin container? This film was made before Lionel Barrymore–on the set of A Free Soul–came up with the idea of hanging a movable mike on an overhead pulley. Furthermore, in order to please the whims of his early-sound audience, Mamoulian provides a great variety of sound effects: traffic, an airplane, boats, the subway, a noisy cash register and even a chewing-gum dispenser, in addition to his razzmatazz musical numbers. A moment of pure silence towards the end of the film is all the more dramatic after that deluge of pure noise.

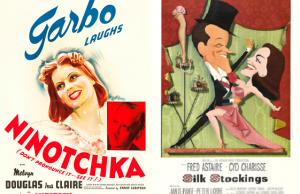

The early critics found the slickness of Mamoulian’s technique quite incredible. After all, this was the first motion picture directed by a Broadway director best known for his mounting of Gershwin’s Porgy. (He later directed the original Broadway production of Oklahoma!, Carousel, and Lost in the Stars among others). The critics even went so far as to attribute some of the sophisticated effects to the producer, Monta Bell. But not so! Over and over again during a somewhat troubled film career, Mamoulian would prove his virtuosity. He experimented with the subjective camera in Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde in 1933. He directed the first three-strip Technicolor feature, Becky Sharp, in 1935. And he directed some of the most original musicals in Hollywood history: Love Me Tonight, Summer Holiday, and Silk Stockings. It is regrettable that he was removed from the direction of both Porgy and Bess and the infamous Cleopatra.

An added treat in this film is the New York City location shooting in the period before the building of even the Empire State Building. This was, for instance, the first film to be shot in the New York subway and in Penn Station. The interiors were shot not in Hollywood, but in Paramount’s then active Long Island Astoria Studios.

The greatest treat of all, however, is the chance to see the legendary Helen Morgan in her first and arguable her best film role. Only 29 years old at the time, she looks as though she has a century of woes behind her. In actual fact, she did. The original Julie of Jerome Kern’s Showboat, she was also representative of some of the living wrecks from the speakeasy days of Prohibition. Her life is the stuff that Hollywood scripts are made of. Naturally, after her death in 1941, many Hollywood actresses were clamoring to play her on film. Jane Wyman even became a blonde! Eventually, it was Ann Blyth who portrayed her (woodenly) in the 1957 film. But help was in sight! Shortly afterwards, Polly Bergen played her in the Emmy-winning Playhouse 90 TV version. The recording of Bergen Sings Morgan is now a collector’s item.

Notes by Cam Tolton

Leave a Reply