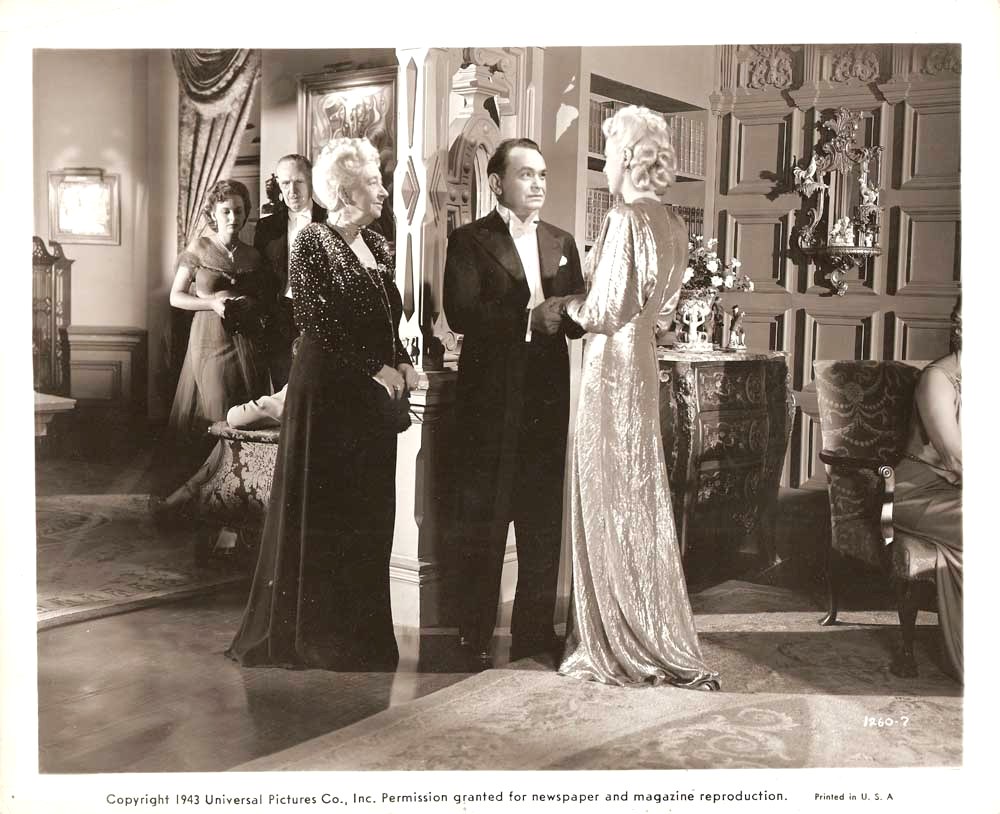

Flesh and Fantasy (1943)

By Toronto Film Society on June 24, 2020

Toronto Film Society presented Flesh and Fantasy (1941) on Sunday, October 5, 1986 in a double bill with The Killers as part of the Season 39 Sunday Afternoon Film Buffs Series “A”, Programme 2.

Production Company: Universal. Producer: Julien Duvivier and Charles Boyer. Director: Julien Duvivier. Screenplay: Ernest Pascal, Samuel Hoffenstein and Ellis St. Joseph, based on stories by Ellis St. Joseph (Episode 1), Oscar Wilde (Episode 2), Laslo Vadnay (Episode 3). Cinematography: Paul Ivano, Stanley Cortez. Music: Alexandre Tansman. Editor: Arthur Hilton.

Cast: Robert Benchley (Doakes), David Hoffman (Davis)

EPISODE 1: Betty Field (Henriette), Robert Cummings (Michael), Edgar Barrier (Bearded Gentleman), Marjorie Lord (Justine).

EPISODE 2: Edward G. Robinson (Marshall Tyler), Thomas Mitchell (Podgers), Anna Lee (Rowena), Dame May Whitty (Lady Pamela Hardwick), C. Aubrey Smith (Dean of Norwalk).

EPISODE 3: Charles Boyer (The great Gaspar), Barbara Stanwyck (Joan Stanley), Charles Winninger (Lamarr), Clarence Muse (Jeff), June Lang (Angela).

The anthology film, made up of several self-contained yet related episodes, may have begun with Intolerance (1916), though the audience’s notorious inability to follow the interweavings of plot in Griffith’s famous film probably then and there set back this sub-genre by twenty years. The first notable film in the category in which Flesh and Fantasy belongs may well be If I Had a Million (1932), in which that number of dollars falls to each of several people. What they do with it constitutes the several episodes, each made by a different director (the best certainly Lubitsch’s direction of Charles Laughton’s protracted Bronx cheer). Other such films of the period or just before included The Bridge of San Luis Rey, in which a number of characters have their lives viewed in retrospect as they go to their deaths in the collapse of the bridge, and the British Friday the Thirteenth, a close copy culminating in a bus accident. While such complexly interwoven works as Grand Hotel and Dinner at Eight have affinities with this sub-genre only in the galaxy of their casts, the type reached its peak in the late 1940s and just after, with the British Maugham anthology pieces, Quartet, Trio, and Encore, and with the American imitation, O. Henry’s Full House (1952). But perhaps the most famous such film, the one most closely related to Flesh and Fantasy, is again British, directed by several hands, Dead of Night (1945).

The director of Flesh and Fantasy, Julien Duvivier (1896-1967), made a minor specialty of such pictures. He directed his first film in 1919, made some of the most notable French films of the 1930s (Pepe le Moko, Le Fin du jour), and was brought to the U.S. to direct in 1938 the rather flatulent The Great Waltz. Perhpas his most famous film to this point had been Un Carnet du bal, in which the eponymous dance card becomes the link in a number of related stories. It was probably on the strength of this that he was assigned Tales of Manhattan, in which a tail coat (much like Rex Harrison’s yellow Rolls-Royce twenty years later) makes its way through several strat of society, and forms a link again between the several episodes of the story. Following this exercise, Duvivier was hired from Fox to Universal to make Flesh and Fantasy, co-produced by Charles Boyer, who had appeared in the earlier film.

What makes Flesh and Fantasy closer to Dead of Night than to Tales of Manhattan is its use of a frame rather than a linking device; this underlines the homogeneity of the episodes, rather than their mere collocation. And as in Dead of Night also, the theme is the supernatural: dreams and other occult means of reading the future. The three episodes are introduced, and somewhat undercut, by Robert Benchley, then at the befuddled height of his popularity as both character actor and in-character explicator of the confusing or recherche facts of everyday (How to Sleep, The Sex Life of the Polyp). The film’s most interesting episode (there was a fourth, split off to make the separate feature Destiny) is certainly the second, based on Oscar Wilde’s “Lord Arthur Savile’s Crime,” in which the central figure, here an eminent American lawyer, has it read in his palm that he will commit murder. Tortured by the thought, he makes several attempts to get the predicted act over with, only to commit it in an entirely unexpected and unintentional way.

Perhaps the main feature of Flesh and Fantasy is that other feature of this type of film: the roster of players. From the placement of their episode, clearly Boyer and Stanwyck are receiving top billing: he fresh from All This and Heaven Too, the first remake of Back Street, and Tales of Manhattan; she fresh from The Lady Eve, Meet John Doe, and Ball of Fire; in the following year she would be the highest paid woman in the United States. But in retrospect Robinson’s performance is the highpoint of the picture, during the period of his playing less gangsters than good men, at odds in some way with the law, in such films as Double Indemnity, The Woman in the Window, Scarlet Street.

Duvivier’s two American anthology films represent one of the highpoints of his career. Over the next quarter of a century he made films in several countries, including a British version of Anna Karenina with Vivien Leigh playing a much more kittenish Anna than Garbo’s, and Ralph Richardson playing a Karenin which thoroughly justified the adultery. He also filmed the same novel of Pierre Louys (in La Femme et la pantin) which Sternberg had used for The Devil is a Woman, and that Bunuel would later use for That Obscure Object of Desire; his most successful film of the later part of his career was the French-Italian production of The Little World of Don Camillo (1951).

Flesh and Fantasy proved more successful at the box-office than Tales of Manhattan, but it has largely faded from audience consciousness. Bosley Crowther, who in the New York Times set forty years of cinematic taste, found it too much for his digestion–“as stuffing and diversified as a four-decker sandwich, complete with mayonnaise and cole slaw.” Savour it as you will!

Notes by Barrie Hayne

You may also like...

-

News

Frances Blau

Toronto Film Society | February 27, 2024On Monday, February 26th, 2024, Toronto Film Society lost longtime friend, supporter, and board member Frances Blau. Known for her sense of humour, her love of film, her generosity,...

-

Special Events

Arsenic and Old Lace (1944) at the Paradise Theatre

Toronto Film Society | April 21, 2024Toronto Film Society presents Arsenic and Old Lace (1944) at the Paradise Theatre on Sunday, May 5, 2024 at 2:30 p.m. Screwball comedy meets the macabre in one of...

Programming

Virtual Saturday Night at the Movies

Toronto Film Society | April 11, 2024Toronto Film Society is back in the theatre! However, we’re still pleased to continue to bring you films straight to your home! Beginning Season 73 until now we have...

4-

Toronto Film Society | April 21, 2024

Toronto Film Society | April 21, 2024

-

Toronto Film Society | November 6, 2022

Toronto Film Society | November 6, 2022

-

Toronto Film Society | August 1, 2023

Toronto Film Society | August 1, 2023

Donate to Toronto Film Society – We’re now a Registered Charity!

-

Copyright © 2017 Toronto Film Society.

Leave a Reply