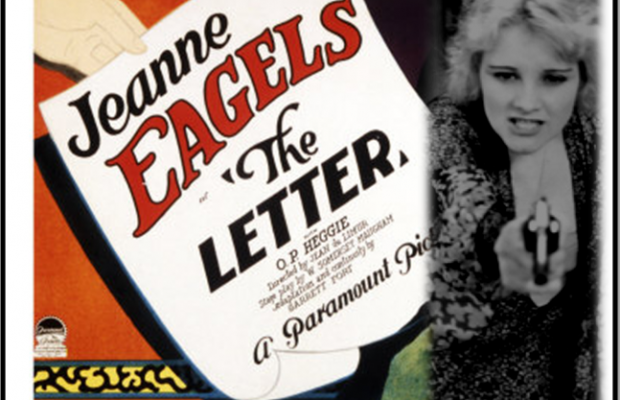

The Letter (1929)

Toronto Film Society presented The Letter on Friday, May 10, 2013 as part of Season 66 May Festival: The Pre-Code Weekend.

The Letter was only recently released by Warners and it was very much anticipated by many film buffs. Since Jeanne Eagles’s in her most famous role, Sadie Thompson, was never filmed, it’s wonderful that we have the opportunity to see the actress on celluloid in another Maugham story. As you know, Bette Davis brought this character to life in the famous and wonderful 1940 remake, so you will be able to compare the two films for their similarities and differences. This being a pre-Code and the 1940 assuredly not, one of the main differences is the ending of each film. If you’ve seen the Bette Davis film, you know that she must pay for her crime of murder as does the wife of the murdered man. Since in a pre-Code, that isn’t necessarily necessary, this film doesn’t disappoint. So you will discover by the last line uttered by Jeanne Eagel’s character, what her punishment actually is. Another difference is that the murdered man’s mistress has to be his wife in the 1940 version. A fun fact is that Herbert Marshall played in both films 11 years apart. In this, his second film, at the age of 39, he plays the murdered lover while in the later version, at the age of 50, he plays the cuckolded husband. In any event, if you haven’t seen the Bette Davis version recently or at all, then you will probably enjoy watching it after the weekend.

Caren Feldman, May 10, 2013

First full length feature made at the Long Island studio of Paramount, and a gripping drama. Distinctive among dialog productions to date in that it creates tension at the outset and holds it until a  magnificent emotional climax. It will fare better in the deluxe houses than within lesser walls.

magnificent emotional climax. It will fare better in the deluxe houses than within lesser walls.

Any summary of the picture must record that the merits of the screen production belong to the original play, written for and played on the stage, and the filming has contributed only atmospheric details. That is to say the production is entirely a transcription of a stage work and the cinema version does little to make the subject matter its own.

It is true that certain pictorial shots and camera angles go to the embellishment of the story, but there is a certain formality about the whole affair that has the stage quality. The same effect is intensified by the fact that progress comes out of the spoken word instead of from essential action, which is strictly an attribute of the stage.

Even if it is a straight canning of a play, however, the result is tense drama. If the process adds little to the original, it does retain all the original’s intrinsic force. It is entirely probable that for the screen educated fans, it is a little fine. Elemental tastes like to have their heroines and their heroes unmistakably heroic. They like to know which characters to admire and which to dislike. The gallery gets a kick out of hissing the villain.

Maugham has a literary trick of drawing his people in half lights composites of good and bad. Leslie Joyce (sic) wasn’t a “bad woman,” just a victim of circumstances playing on a weak creature. Under the spur of impending doom she took on a certain boldness, but she was generally a drifting, indefinite sort of person. Her husband was a well intentioned dumbbell. Even the Chinese woman had admirable traits of loyalty and a sense of justice. There isn’t a character in the play you can really admire or actively hate. This is all very confusing to the gallery clients who want to hiss the villain.

It is an acting triumph for Miss Eagels. She is called upon for unusual shading of mood. Trial scene is capital. The woman who had murdered her faithless lover brings all her feminine arts to play in creating the impression she wants on the jury. Dainty handling of this passage. The climax is immense in its power, certainly the peak of emotional intensity so far recorded on the articulate screen.

Dialog sequences are uniformly excellent in voice recording. Miss Eagels dicting reproducing particularly well. Several passages in which two native characters speak in their own tongue also are first-rate atmosphere. Scenes of the crowded, narrow Shanghai streets in weird shadow effects, eerie corridors full of Oriental mystic atmosphere, and the boiling crowds of the Chinese dives—all these angles are graphic and lie, made more so by shrewd sound incidentals.

One item is questionable. During the scene in a Chinese dive whore the white woman confronts her yellow rival, the crowd out in the assembly place are gathered around a table upon which there is  supposed to be a fight between a hooded cobra and a mongoose. Here the producer has spliced in sections from the Ufa short subject which has been shown all over the country. The crowd at the film’s premiere identified it instantly and the effect on the spectators was distinctly bad, introducing as it did a brutal jolt to the whole illusion.

supposed to be a fight between a hooded cobra and a mongoose. Here the producer has spliced in sections from the Ufa short subject which has been shown all over the country. The crowd at the film’s premiere identified it instantly and the effect on the spectators was distinctly bad, introducing as it did a brutal jolt to the whole illusion.

If they’re absorbed in what is taking place in a baudy house in Shanghai, and suddenly the snake fight makes them recall that they saw the same thing in the same or another theatre a month ago, the illusion is killed.

Atmosphere of these dive scenes is remarkably well developed in other directions. There is a native dance for the edification of the riff raff crowd, done by three native girls and the last word in sexy display, but discreetly handled and innocent of offense. Whole picture has been governed by sound dramatic judgment and fine taste.

In short, it is a production that will contribute to the prestige of its maker and of the screen and will prosper in the deluxe houses, but probably fare just moderately in general release. .

VARIETY, Rush , March 13, 1929

THE LETTER, Paramount production and release directed by Jean De Limur. Made from play of same name by Somerset Maugham with adaptation and continuity by Garret Fort. Monta Bell producer. Cameraman, George Folsey. W.E. synchronization on disk.

An audible photoplay that defies the derision that has been flung at so many specimens of this type of entertainment was offered last night at the Criterion Theatre by Paramount-Famous-Lasky. It is the talking pictorial version of W. Somerset Maugham’s play, “The Letter,” which has been intelligently produced and most competently acted. It is the first offering of its kind in which there are true passages of life-like drama, a fact that is chiefly due to the ability of players, who are all known to the stage.

In the last few scenes, Jeanne Eagels, who impersonates Mrs. Leslie Crosbie, a part played on the stage by Katharine Cornell, senses the full power of her role. It is where Leslie Crosbie, after being acquitted of the murder of her lover, Geoffrey Hammond, in a tirade against her husband for having brought her out to the dismal life on a rubber plantation, near Singapore, tells him that she still loves the man she sent to his death. These stretches are not only stirringly performed by Miss Eagels, but the mechanical contrivances hold up through the difficult task of reproducing her passionate condemnation and virtual excuse for the murder.

In other sequences the portrayals of O.P. Heggie, as the lawyer for Mrs. Crosbie, Reginald Owen, as the husband and Herbert Marshall as Geoffrey Hammond, are, if anything, better than the interpretation of Miss Eagels. For during certain interludes Miss Eagels appears neither to take her love affair or the trial with the seriousness one anticipates.

The keynote of this melodrama is given by Hammond when he is discovered reading Oscar Wilde’s “Ballad of Reading Gaol” to his Chinese mistress. Hammond is heard droning:

“Yes each man kills the thing he loves,

By each let this be heard.

The coward does it with a kiss,

The brave man with a sword.”

Jean de Limur, a French director, has taken advantage of the scope of the screen, but, so far as incidental sounds, he appears somewhat unimaginative, for during those periods when there is no conversation he relies on Oriental music to help out the audible effect. He has, however, introduced some excellent camera work, notably in an early chapter, when he travels with his camera through  trees and bushes before arriving at the portals of the Crosbie bungalow. Here it seems as though he sweeps through the foliage and by tree branches before coming to the little light that glows from the room in which Mrs. Crosbie and her husband are first seen.

trees and bushes before arriving at the portals of the Crosbie bungalow. Here it seems as though he sweeps through the foliage and by tree branches before coming to the little light that glows from the room in which Mrs. Crosbie and her husband are first seen.

In the Chinese sequence Mr. de Limur has the temerity to take a lesson from that wonderful Ufa short film, “Killing the Killer,” for he presents the absorbing fight between a mongoose and a cobra in which the former triumphs. There is also in this chapter a forbidding looking stairway down which Mrs. Crosbie staggers to obtain the letter, for which she has to pay $10,000 to the Chinese woman.

Although there are occasional suggestions in the players’ lines of the unfortunate lisping, it is not nearly so noticeable as it has been in most of the other dialogue productions. The voices are invariably wonderfully natural and marvellously distinct, without being too laud. The players have evidently, through Mr. Limur’s adroit direction, realized the necessity for restraint both in their utterances and in their actions.

The murdered man was never seen on the stage, or, at least, one merely saw a prostrate figure. In this picture not only is the slaying portrayed on the screen but there is a fairly well wrought, although rather Americanized, trial scene. It is effective in many respects, but to those who have seen trials in British courts it is a poorly copied idea with shrewdly sustained dramatic effects that are never prolonged to a tedious point. In fact this compactness applies to the production as a whole, for whatever shortcomings may arise they never kill the interest in the action of the narrative. One might say, for instance, that a feature of the play was the clothing of the actors. These people on the stage looked in their careless attire as if they might have come from Singapore, whereas in the picture the male characters are all far too neat. Only once in the picture does one obtain any conception of the heat of that part of the world, and that is in the courtroom scene, where people are fanning themselves and the judge mops his brow.

The story told by Mrs. Crosbie on the witness stand, instead of in the dock, is rather feeble, but the excuse for this would be that Mrs. Crosbie is falsifying her testimony as she goes on.

NEWYORK TIMES, by Mordaunt Hall, March 8, 1929

Notes compiled by Caren Feldman

A good summary, but it’s funny that none of the contemporary reviewers noted how greatly the film varies from Maugham’s dramatization of his short story. The film presents the shooting after it shows Mrs. Crosbie’s confrontation with Hammond, not as the opening. It also adds the powerful confrontation scene between Mrs. Crosbie and “the Chinese Woman.” In the play, Joyce handles the transaction. Mr. Crosbie also knows about the letter much earlier in the play. The Letter has some of the static quality of a filmed play, but it is far from a literal reproduction of Maugham’s script.