Potemkin (1925)

By Toronto Film Society on October 16, 2016

Toronto Film Society presented Potemkin (1925) on Monday, March 16, 1959 as part of the Season 11 Monday Evening Silent Film Series, Programme 5.

The Soviet Film: Developments in the ’20’s

Kino-Pravda (USSR 1922). Produced by Kultkino, Mosco. Supervised and Edited by Dziga Vertov. Photography by Mikhail Kaufmann and other members of the Kino-Eye group.

Examples of the style of the weekly newsreels of the period, which sought to report to the people “every step toward socialism” and “the life of the entire country”. The Kino-Eye men, in their zeal for their theory of the camera eye as a witness to actuality, even recommended that “all other production be jettisoned”.

Kimbrig Ivanov (USSR 1923) (Excerpt). Directed by Alexander Razumni.

In spite of Kino-Eye manifestoes, fiction films still formed the bulk of production. New themes were shown with the old techniques, as in Kombrig Ivanov. This picture appears to have been re-christened The Beauty and the Bolshevik, presumably in America!

Rebellion: Mutiny in Odessa (France 1906). Produced by Pathe Freres, Paris. Directed by Ferdinand Zecca.

The only contemporary films about the 1905 Russian Revolution were made in France by Zecca (maker of some of the short French comedies we saw this season). Rebellion has been included in this programme for the interest of comparing this early, primitive treatment of the Potemkin mutiny with Eisenstein’s full-length, cinematically developed version that follows.

INTERMISSION

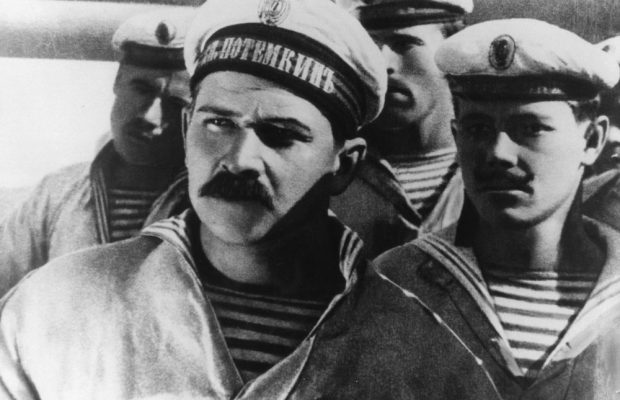

Potemkin (USSR 1925). Produced by the First Studio of Goskino, Mosco. Directed by Sergei M. Eisenstein. Photographed by Edouard Tisse. Assistant Director: Grigori Alexandrov. Cast: Sailors of the Red Navy; citizens of Odessa; members of the Proletcult Theatre; A. Antonov (Vakulinchuk); Grigori Alexandrov (Chief Officer Giliarovsky); Vladimir Barsky (Captain Golikov).

Originally intended as a 42-shot episode only in a large-scale work called 1905, the Potemkin mutiny first was expanded into the central episode, then became the entire film as all other material was dropped.

The Museum of Modern Art Film Notes point out that Potemkin “often sacrificed the historical facts for dramatic effect”, and go on to say: “Not the least of the accomplishments of Potemkin was the understanding with which Eisentein and his cameraman (schooled in the war-newsreel) worked together. Tisse’s ingenuity was ideal for Eisenstein’s invention. The slaughter on the steps needed original filmic techniques; a camera-trolley was built the length of the steps. Several cameras were deployed simultaneously. A hand-camera was strapped to the waist of a running, jumping, falling assistant. The total construction and frame-compositions of Potemkin were gauged and carried out with particular juxtapositions in mind. The shots taken on the steps were filmed looking forward to the cutting table as much as were the famous shots in which three different marble lions become one single rearing lion. Heretofore the movement of a film depended largely on the action within the sequence of shots. Eisenstein now created a new film rhythm by adding to the content the sharply varying lengths and free associations of the shots, a technique growing directly from his interest in psychological research. Besides the behavioristic stimulation made possible by this method, a new range of rhythmic patterns and visual dynamics was opened by Potemkin.”

Eisenstein himself (who, incidentally, acknowledged his debt to Griffith in the evolution of his techniques) said: “It is a question of creating a series of images composed in such a way that it provokes an affective movement which in turn awakens a series of ideas. From image to sentiment, from sentiment to thesis–the film alone is capable of making this great synthesis, of giving back to the intellectual element its vital sources, both concrete and emotional.”

Paul Rotha called Potemkin and Ten Days That Shook the World (which we shall endeavor to show next season) “the greatest examples of epic mass film”, pointing up their use of people as groups rather than individuals (Pudovkin being more concerned with the latter). “These films give a full realization of the spirit of the Russian people. On the score of their epic quality, as apart from their propagandist intention, they deserve to be shown freely throughout the world”. (For many years, of course, they had great difficulty in this respect due to censorship.)

Rotha continues: “Eisenstein is essentially impulsive, spontaneous and dramatic in his methods. He does not work from a detailed script like Pudovkin, for he has not the deliberate, calculating mind of the latter. He prefers to wait until the actual moment of production and then immediately seize upon the right elements for the expression of his content. It is of note to recall that neither the famous Odessa steps sequence, nor the misty harbor shots, were in the original script for Potemkin; but as soon as Eissenstein reached Odessa and found these features, he at once expanded his script to include them. He is thus a brilliant exception to the theory of complete preconception.”

In their History of the Film, Bardeche and Brasillach say: “The unequalled concentration and conciseness of Potemkin, its amazingly dramatic moments, all owe their power to the film alone. It is a reconstruction which attains the direct truthfulness of a documentary film, but it is also a document which becomes a work of art, created deliberately, in which propaganda itself disappears before the eternal humanity of the true story of a struggle between oppressors and oppressed.” These writers go on to claim, however, that “the Russians themselves did not at first care very much for their masterpiece; it was the Germans who made its fame, and for a long time Potemkin was announced in the Moscow cinemas as ‘the great Berlin success’.”

His great colleague Pudovkin said of Eisenstein: “Once can neither describe his work, nor represent it on a stage; one ca only show it on the screen.”

FOOTNOTE: For what it is worth, Potemkin headed the very controversial list of the “best films of all time” selected by a sizable group of film historians and critics at the behest of the Brussels Festival.

The Films of S.M. Eisenstein:

Strike.

Potemkin.

Ten Days that Shook the World (October).

The General Line (The Old and the New).

Que Viva Mexico! (Uncompleted): (Thunder Over Mexico, Time in the Sun and Death Day are versions edited by others).

Alexander Nevsky.

Ivan the Terrible. (Planned as a great trilogy, the second part was supressed for many years by the Soviet Government, but has now been released and may be available locally before long. Part III was never made.)

You may also like...

-

News

Frances Blau

Toronto Film Society | February 27, 2024On Monday, February 26th, 2024, Toronto Film Society lost longtime friend, supporter, and board member Frances Blau. Known for her sense of humour, her love of film, her generosity,...

-

Special Events

The Ladykillers (1955) at the Paradise Theatre

Toronto Film Society | March 9, 2024Toronto Film Society presents Targets (1968) at the Paradise Theatre on Sunday, April 7, 2024 at 2:30 p.m. Ealing Studios arguably reached its peak with this wonderfully hilarious and...

Programming

Virtual Saturday Night at the Movies

Toronto Film Society | April 11, 2024Toronto Film Society is back in the theatre! However, we’re still pleased to continue to bring you films straight to your home! Beginning Season 73 until now we have...

4-

Toronto Film Society | March 9, 2024

Toronto Film Society | March 9, 2024

-

Toronto Film Society | November 6, 2022

Toronto Film Society | November 6, 2022

-

Toronto Film Society | August 1, 2023

Toronto Film Society | August 1, 2023

Donate to Toronto Film Society – We’re now a Registered Charity!

-

Copyright © 2017 Toronto Film Society.

Leave a Reply