Kid Monk Baroni (1952)

By Toronto Film Society on January 26, 2020

Toronto Film Society presented Kid Monk Baroni (1952) on Sunday, January 26, 2020 in a double bill with Fear in the Night as part of the Season 72 Sunday Afternoon Special Screening #4.

Production Company: Jack Broder Productions Inc. Producer: Jack Broder. Director: Harold D. Schuster. Screenplay: Aben Kandel, with additional dialogue by Dick Conway. Music: Herschel Burke Gilbert. Cinematographer: Charles Van Enger. Editor: Jason H. Bernie. Art Direction: James W. Sullivan. Set Decoration: Edward G. Boyle. Release Date: May 1, 1952.

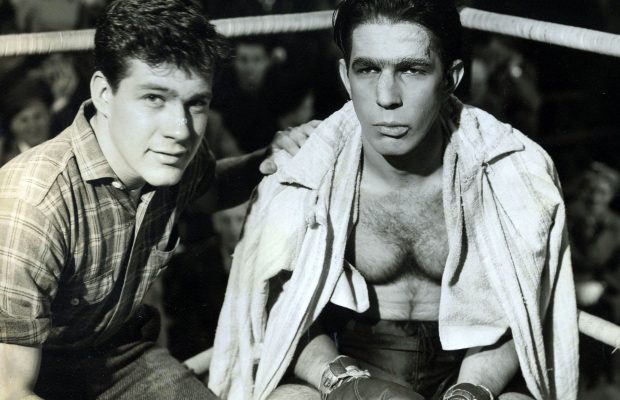

Cast: Leonard Nimoy (Paul “Monk” Baroni), Richard Rober (Father Callahan), Bruce Cabot (Mr. Hellman), Allene Roberts (Emily Brooks), Mona Knox (June Travers), Jack Larson (Angelo), Budd Jaxon (Knuckles), Archer MacDonald (Pete), Kathleen Freeman (Maria Baroni), Joseph Mell (Gino Baroni), Paul Maxey (Al Petry), Stuart Randall (Mr. Moore), Wayne Mallory (Tony), Ted Avery (Joey), Madelynn Broder (Little Girl in Church).

The Good, the Bad, and the Ugly:

Kid Monk Baroni is fundamentally a movie about beauty. Paul Baroni, played by Leonard Nimoy, is born with a disfigured face into an immigrant family in a rough part of New York. We are introduced to him and his gang of friends as they saw off a handrail inside a condemned tenement building, for firewood. A good-hearted and enlightened Irish priest, played by Richard Rober, comes along and turns them away from a life of crime by giving them a warm boxing gym in the basement of his church in which to hang out. Although Father Callahan only ever makes vague allusions to God, he readily teaches Paul about the finer points of culture, including music, literature, vocabulary, and proper pronunciation.

Through a mishap, Baroni is alienated from his newfound support structure, and comes to the conclusion that somebody who looks like him could only ever box. Once he starts boxing professionally, he is repeatedly confronted with the booing of the crowd and astutely observes that fans flock to watch him get hurt or possibly killed. It’s an interesting comment on the sport of boxing and, by extension, the genre of boxing films, that the ring offers both the source of salvation and the cage in which “punch drunk gargoyles” are displayed. One is reminded of the way the side-show is used in Freaks (1932) and other such movies to display the humanity of those on display and the monstrosity of the audience. Of course, the social commentary in Kid Monk Baroni is somewhat less pointed, and Baroni himself is somewhat less sympathetic throughout. Ultimately, the film seems to be a moral tale, but the message is a bit perplexing. Rather than contrasting Baroni’s external ugliness with an inner strength of character, it contrasts it with an inner aesthetic sensibility, including the fact that he likes choir music and is a good dancer. Although his climactic act is one of charity, the undercurrent throughout the film appears to be purely aesthetic. In the end, it seems the audience is left to think, “I guess it’s ok if you’re ugly as long as you have good taste.”

Critical Disabilities and Kid Monk Baroni:

There is an interesting exchange in the film in which someone reminds Baroni that he could do anything and therefore doesn’t need to box. Baroni simply reiterates the point, “With this face?” It is a good illustration of what scholars of critical disabilities call the Social Model of disability. According to the way disability is typically understood in society—the Medical Model—disability is a physical fact about an individual’s body that must be treated through medical means. The Social Model counters that, though there may be a physical impairment, that alone does not make a disability; rather, it is the societal treatment of that physical fact which turns it into a disability. Ugliness is an effective way to illustrate this difference because there is no rational reason why ugliness should impair Baroni’s ability to be a musician or an accountant, for example. Whereas the Medical Model of disability recommends plastic surgery, the Social Model recommends changes in societal structures and attitudes. Above all, the film is a reminder of what a huge impact comparatively minor and arbitrary facts about us can have on our lives. The disabilities movement has always sought emancipation from the tyranny of these facts and the institutions that reinforce them.

Break-out Role for Leonard Nimoy:

Kid Monk Baroni was a break-out role for Leonard Nimoy, but not quite the one he wanted. He was hoping that this film would lead to more leading roles, but the movie failed after a short run. While Nimoy served in the military, however, Kid Monk Baroni did garner a larger audience on television. This led to his getting steady work on TV as a “heavy”—an intimidating character who uses street weapons. This would in part set the pattern for Nimoy of pursuing supporting, rather than leading, roles. Nevertheless, according to an article on Leonard Nimoy by film writer Greg Carpenter, the role of the sensitive boxer was a quintessential role for method actors honing their skills at that time. He points out, “Two years after Nimoy’s turn as Baroni, Brando would win an Oscar for On the Waterfront, and two years after that, Paul Newman would fill in for James Dean in Somebody Up There Likes Me.” This comment makes a lot of sense, given what Nimoy said about his experience of wearing the prosthetics in Kid Monk Baroni in his autobiography, “I am Not Spock”: “I was not a thoroughly trained actor, but instinctively, my emotions began to respond to my new appearance. I could begin to identify with the internal life of this face—the insecurities, the retiring shyness, the bursts of anger, the paranoia.” The further irony is that Kid Monk Baroni is typecast in the ring as a dirty fighter, precisely as he would eventually become.

The Billy Goat Gang:

A November, 1951 news item in The Hollywood Reporter stated that Kid Monk Baroni was to be the first entry in a proposed series with “The Billy Goat Gang”—the name of the gang which Baroni leads—but no additional films were produced. Although onscreen credits read “Introducing Leonard Nimoy”, he had actually made his screen debut (as Leonard Nemoy) in the 1951 United Artists film Queen for a Day. Kid Monk Baroni did, however, mark the motion picture debut of Archer MacDonald.

Notes by Benjamin Miller

SPOT THE CANADIAN

Today’s double-bill features just a single Canuck, but what a Canuck! Edward G. Boyle, set decorator for Kid Monk Baroni, was born on January 30, 1899 in Cobden, Ontario. Thirty years later, he left home to try his luck in Hollywood. Boyle’s talent and determination launched his film career in the early-1930s and it lasted until the end of the 1960s. Along the way, he worked on over 100 films, with credits including an assist on dressing the post-Civil War ravaged south in Gone with the Wind (1939); poking fun at Nazi regalia in Chaplin’s The Great Dictator (1940); taking on the scuzzy underworld of boxing in Body and Soul (1947) and Champion (1949); and channelling elegance and exotica in Separate Tables (1958), Hawaii (1966), and The Thomas Crown Affair (1968). Boyle, a favourite of director Billy Wilder, was nominated for an Oscar seven times, winning once in 1960 for The Apartment. His other nods were for The Son of Monte Cristo (1940), Some Like it Hot (1959), The Children’s Hour (1961), Seven Days in May (1964), The Fortune Cookie (1966), and Gaily, Gaily (1969). He died in LA in 1977.

Written by Leslie C. Smith

You may also like...

-

News

Frances Blau

Toronto Film Society | February 27, 2024On Monday, February 26th, 2024, Toronto Film Society lost longtime friend, supporter, and board member Frances Blau. Known for her sense of humour, her love of film, her generosity,...

-

Special Events

Monday Evening Film Noir Double Bill at the Paradise Theatre

Toronto Film Society | July 8, 2024The Toronto Film Society presents a film-noir double feature at one low price! The Window (1949) in a double bill with Black Angel (1946) at the Paradise Theatre on Monday, August...

Programming

Virtual Saturday Night at the Movies

Toronto Film Society | July 20, 2024Toronto Film Society is back in the theatre! However, we’re still pleased to continue to bring you films straight to your home! Beginning Season 73 until now we have...

4-

Toronto Film Society | July 8, 2024

Toronto Film Society | July 8, 2024

Monday Evening Film Noir Double Bill at the Paradise Theatre

-

Toronto Film Society | November 6, 2022

Toronto Film Society | November 6, 2022

-

Toronto Film Society | August 1, 2023

Toronto Film Society | August 1, 2023

Donate to Toronto Film Society – We’re now a Registered Charity!

-

Copyright © 2017 Toronto Film Society.

Leave a Reply