Paris 1900 (1947)

Toronto Film Society presented Paris 1900 (1947) on Monday, February 8, 1954 as part of the Season 6 Main Series, Programme 7.

SUBSTITUTE FEATURE, FEB. 8, 1954

Regretfully we announce that for the first time in five Seasons

the scheduled feature has not arrived: Paris 1900 has been lost

in transit between New York and Ontario. However we are happy

to have obtained a film which the Society has wanted to screen

for several seasons and which has just become available —

Le Corbeau France 1943

Directed by Henri-Georges Clouzot

Photography: Nicholas Hayer. Script: Louis Chavance.

Music: Tony Aubain. Cast: Pierre Fresnay (Germain);

Pierre Larquey (doctor); Ginette Leclerc (crippled girl);

Helena Manson, Micheline Francey, Jeanne Fusier-Gir.

CLOUZOT (born in 1907) came into the cinema world as a scenarist. After making a competent thriller L’Assasin Habité au 21, he suddenly presented Le Corbeau which became, in France, the most discussed film in years. After the Liberation it was banned for a time and the director and script writer were both totally suspended from their functions. Although Le Corbeau was conceived before the German Occupation (it was made under it) its devastating picture of French provincial life was regarded by the Germans as useful propaganda and it was released in Germany (re-titled Eine Kleine Stadt) as an example of the degeneracy of French provincial life. In 1947 Clouzot made Quai Des Orfèvres.

On the surface, Le Corbeau is a detective story–complex in plot and with numerous characters. In drawing the audience into the game of unravelling the mystery, Clouzot reveals an outlook which almost involves all of us in guilt. His clinical analysis of human weakness and failure is presented with virtuosity. The film is a masterpiece of skill: the director has an uncanny sense of what effect angles, sudden transitions, and sounds can make. The dialogue is harsh and excellent, the acting, admirable.

Hollywood remade this film in 1951, titling it The 13th Letter.

SEVENTH EXHIBITION MEETING – SIXTH SEASON

Monday, February 8, 1954 8.15 p.m. sharp

Royal Ontario Museum Theatre

Paris 1900 France 1945-46 76 mins.

DIRECTION & SCENARIO

EDITOR

MUSIC

PRODUCTION SUPERVISOR

ASST. PRODUCTION SUPERVISOR

ASSISTANT EDITOR

ENGLISH ADAPTATION

ENGLISH NARRATION

ENGLISH VERSION EDITOR

FRENCH SONGS SUNG BY

: Nicole Vedrès

: Myriam

: Guy Bernard

: Claude Hauser

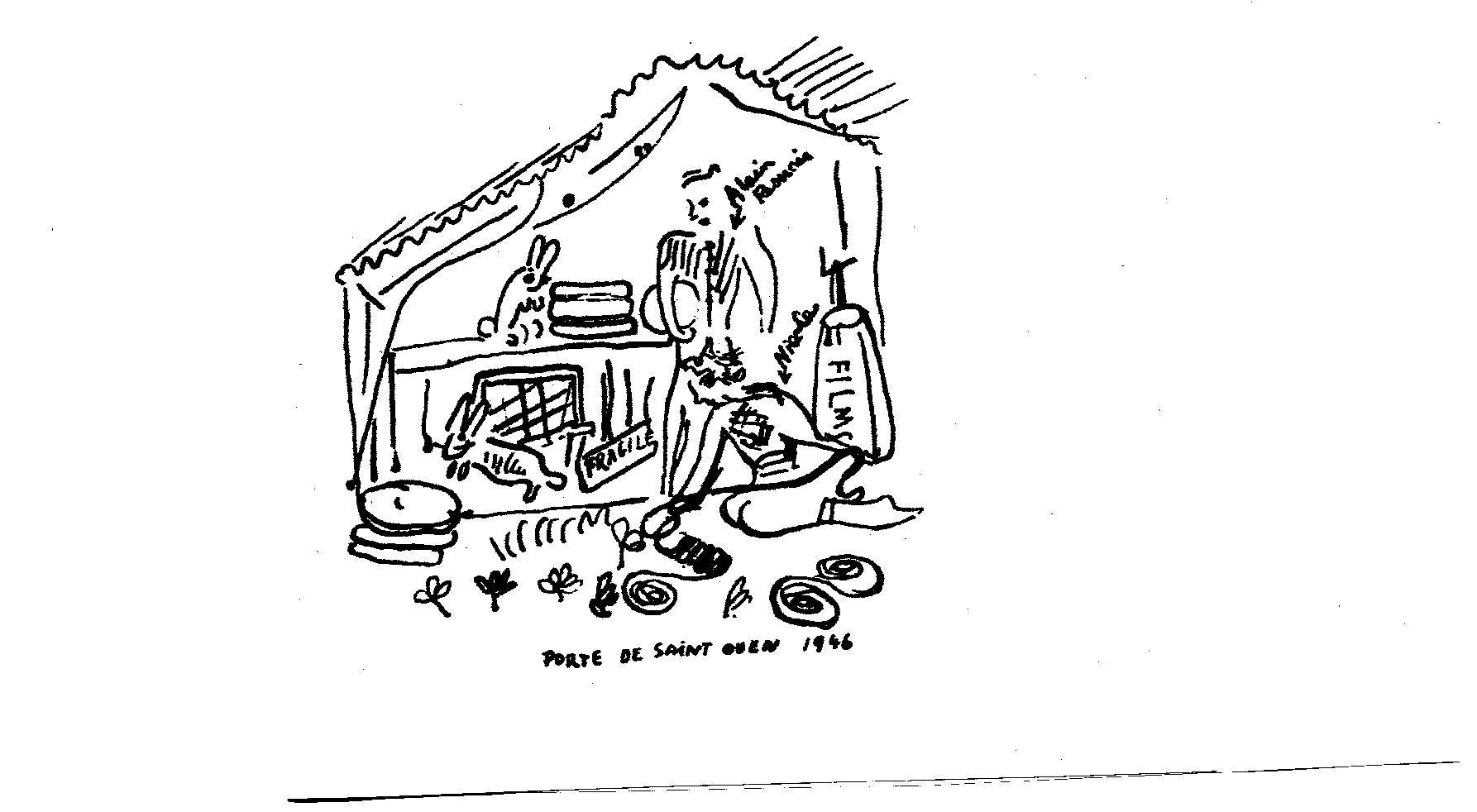

: Alain Resnais

: Yannick Bellon

: John Mason Brown

: Monty Wooley

: Reine Dorian

: Claude Dauphin

Nicole Vedrès’ witty and entertaining re-creation of Paris

between the years of 1900 and 1914 is a brilliantly edited

compilation of early French newsreels and fiction films.

Among the notables glimpsed in the film are – Monet, Renoir,

Gide, Valéry, Cécile Sorel, Mistinguett, Réjane, Bernhardt,

Carpentier, Chevalier, Colette, Rodin, Melba, Debussy, Léon

Blum, Tolstoy, Buffalo Bill.

writes Toronto Film Society:

PARIS, 1953

Paris 1900 seems now a very old story. Not so much because it tells about the Paris of 53 years ago, but because it was made in 1945-46…. Half a century is not a very long time with regard to History, but ten years are very much in a person’s life. Though I am supposed to be this person, and the author of the film, I remember rather a sort of monster working for over one and a half years and not knowing itself what would come out of it; a monster who had my face perhaps, but who had the eyes of Alain Resnais**, the ears of musician Guy Bernard, the hands and gestures of editor Myriam, and, finally, the voice of Claude Dauphin.

The monster, working on history, tried to be honest. That means, we tried to be impartial as one can be–which does not amount to much, anyway–we tried not to impress our modern vision on old times, not to draw our actual conclusions from ancient problems. Indeed we tried to see–and did see–that these ladies were beautiful, these artists talented, these crowds hopeful, that these sportsmen believed in the future of sports, these Don Juans in the virtue of moustaches, these presidents in the eternity of peach, these businessmen in the regularity of progress. Even more, we tried to take the whole lot–story, scenery, facts, faces, fates–as a “tout”, as one personnage whole life, loves, deeds, errors or performances made him the unique hero of a novel, a novel that ended tragically–although no one can tell, even now, whether it was by crime, accident or suicide–in August, 1914.

Since the completion of the film, many people seem to have been interested in hearing what sort of technique we applied to the work. It was only when trying to answer such questions that we–the monster–discovered we had none. For about 15 months we just looked at old newsreels and also some features–most of them in such bad condition that we could never foresee whether or not they could be reprinted.

And where did we find our films?

Anywhere. Just anywhere.

…In garrets ..blockhouses ..cellars…

garbage bins …marche aux puces

(flea markets)…

…and even once in a cabane a lapins

(rabbit hatch) where, during the war,

someone had hidden part of a

collection…

…and sometimes, though seldom, in

film libraries…

When we had finally found and selected our films, we put the pieces together and made the story. The, for quite a long time, the monster worked on the music and commentary, two hands on a piano and another holding a pen. A film made of selected silent pictures is, for an author, the best occasion to talk, not to make actors talk, but to talk himself, to give voice to things, facts–not only to faces. This is, perhaps, the only moment where a sort of technique intervenes: the combination of words and pictures–and music–is quite a mysterious and rigorous work. One must not explain nor describe. Quite the contrary. One must go, as it were, through the first appearance of the selected shot to feel and, without insistence, make felt that strange and unexpected “second meaning” that always hides behind the plain and superficial subject. this bearded gentleman–a politician–though very smiling and quickly walking seems sinister. Or rather, he does not, but the picture does. Why? Maybe only because he walks from right to left…. Why is this landscape agreeable, even most comforting, although the trees have no leaves, and the road is very empty? Maybe it is only the proportion of the sky in it, the allure of the clouds. Why is this interior scene extremely elegant, although neither the lady sitting there, nor her dress, nor the furniture are beautiful, or even witty? Maybe only by the way in which, on the old celluloid, blacks and whites combine! And so you will take two or three metres of the bearded gentleman with appropriate music (or silence) and place him just at the moment (1913) when rumours of war take place. The comforting landscape on the other hand could be used just when the word “hope” has to be said, and the “interieur raffiné”–again not more than two metres of it–can just follow a hint of Marcel Proust. And so on…

It would have been great fun for the monster to be able to see the film presented abroad, to an audience which, though well aware of history, French taste, Parisian spirit, would not be quite familiar with all the scenes and people presented in Paris 1900, an audience with as much curiosity as a French one but with fewer memories. The, and only then, could we see for once whether or not we had succeeded in “going through” appearances, if, indeed, we had achieved our purpose of telling “the story behind the story”. Toronto 1954 seems to be the nicest place for such an experience. So these few lines are written in a very approximate English to present to our friends of the Toronto Film Society this silent picture which talks very much, which, although made of “facts” is not realistic at all, and which, in spite of its classification as “historical film”, is neither quite “history” nor, I’m afraid, cinema …….

Nicole Vedrès

** At that time “assistant”, and since then director of many films on art, including Van Gogh, Gauguin, Guernica…..

I N T E R M I S S I O N

Cops U.S.A. 1922 approx 20 mins. at 24 f.p.s.

DIRECTED by Buster Keaton and Eddie Cline with Keaton

Two reels of the comedian’s brilliant style at the beginning of his maturity. “Keaton in Cops took a purely Keystone subject and multiplied and magnified it to its last degree of development: thousands of policemen rushed down one street, equal thousands rushed up another; and before them fled this small, serious figure, bent on self-justification, caught in a series of absurd accidents, wholly law-abiding, a little distracted.”

Gilbert Seldes – Seven Lively Arts

David Great Britain 1951 38 mins.

WRITTEN & DIRECTED BY: Paul Dickson

PRODUCER: James Carr

PHOTOGRAPHY: Ronald Anscombe

EDITORS: Kit Wood, Morag Maclennan

MUSIC: Grace Williams

CAST: D.R. Griffiths (Dafydd Rhys), John Davies (Ifor Morgan), Sam Jones (Rev. Mr. Morgan), Rachel Thomas (Mrs. Morgan), Mary Griffiths (Mary Rhys), Gwyneth Petty (Mary Rhys as a young girl), Ieuan Davies (Dafydd Rhys as a young man).

Commissioned by the Welsh Committee of the Festival of Britain, David was made by Paul Dickson whose film The Undefeated was shown in the 1951-52 season. One of the few authentic regional films made in Britain, David was shot on location in the town of Ammanford in Wales. It reasserts the human values that documentary film-making has lacked for so long.

D.R. Griffith, as Dafydd, relives on the screen episodes from his own life; the players with the exception of Gwyneth Petty (from the stage) are non-professional.

Edgar Anstey comments on the importance of the film: “David seems to me to point the way for a new type of documentary film which may develop the combined qualities of Western Approaches, North Sea and other examples of the factual story film. One of the weaknesses of the story documentary has been that its characterization has generally remained on a superficial level, its people have often been subordinated to a stiuation and have remained lay-figures. In David we see this problem overcome, characters are fully developed and yet the situation from which they grow remains convincingly authentic, is ‘documentary’ rather than ‘fictional’. The film succeeds in probing down into the situation and reaching the roots of the principal character.”

This moving and beautiful film received a limited commercial distribution in Toronto.

CURRENT FILM NOTES

Those who still think of Bing Crosby as the “crooner” of 20 years ago may not realize that he has developed into one of the screen’s most easy and assured performers. He is at his best and has his best film in Little Boy Lost–a story that could have been maudlin sentimentality, but has been written and directed by George Seaton with such rare taste, discretion and intelligence that it becomes a moving screen experience. The young French boy Christian Fourcade gives a remarkably true and touching performance that ranks with many of the portrayals of bereaved postwar youth in European films. The film is immensely strengthened by the supporting performances of such artists as Gabrielle Dorziat and Claude Dauphin; by the fact that it was shot on location in France; and by Victor Young’s sensitive, haunting background score.

The Sinner is a tragic German romance that I found fascinating. Willi Forst’s direction is highly effective visually (photography is especially fine) and the sound track is mostly taken up with the heroine’s narration of her story. This is spoken by Hildegarde Neff in English, is quite effectively done and does away with a lot of tiresome “dubbing”. Miss Neff, Gustav Froelich and the rest perform most persuasively.

MEMBERS’ EVALUATIONS ON THE CHRISTMAS PROGRAMME: “The best programme of the current season and one of the best you have offered to date”—“The general atmosphere, the piano accompaniment and the old-time slides during reel change, very well done; would like to voice my approval of having a program of this type once each season.”

Mickey: “A fine example of one of the milestones in film history; a surprise how ‘ahead of its time’ this film classic was; easily seen why Mabel Normand so popular”—“Mabel a charming performer; very enjoyable; surely no one will have the heart to say they didn’t like it!; a treat to be able to see it; a great big thank you to those responsible for choosing it to be shown; and to Ruby Ramsay Rouse for her wonderful contribution”.

THE PRODUCTION GROUP’S TRAILER: “The Film Society short on’8:15 p.m. sharp’ deserves praise for imagination and following out of ideas”—“An exciting experience; ending magnificent”.

Night on Bare Mountain: “Quite imaginative”—“The only blot on the evening’s entertainment; process may be interesting but subject handled in most horrible manner”.

Hen Hop: “Unmistakably Norman McLaren’s work and as such, unusual, interesting and comical”—“McLaren is always a treat”.

The Pawnshop: “Hilarious; Chaplin, the greatest of all comedians at his best”—“Still an experience to view again; how did the popular ‘gag’ type of comedy ever replace this silent wonder?”

MEMBERS’ EVALUATIONS ON Hallelujah: “The best of the half-century”—“Terrible!–a classic collection of racial stereotypes; an imposition, if not an insult, to T.F.S should never have been shown”—“A beautiful film done in a sincere, straightforward way; characters vividly drawn, emerged as real people in true-to-life story; matching of sound track with lip movement of actors remarkably well done considering the pioneering in this field going on at time this great film was made”—“Vidor looked and listened much, understood little; do the peasants in ‘Fontamara’ have an existence separate from the landlords? Do Negroes and whites have separate existences? Amazing how idealized Negro peasant life was; ‘Uncle Tom’ attitude; why wasn’t it shown in the South? It’s a typical expression of the white Southerner’s attitude”—“Well worth seeing for content and as a piece of film-making; terrific impact of religious rites; beautiful simplicity; historical interest; integration of music and dance a natural part of life of the people; Richard Griffith would impose on the film an element quite foreign to the maker’s intention, to show conflict of sexual and religious drives in these people; Vidor beautifully filmed these manifestations at one period in their history; that the expression of these manifestations have changed since makes the work quite unique”—“Certainly a splendid film”—“Rituals, songs and dances authentic”—“A strong, moving, honest film; liked it a lot; realism terrifically exciting; some abrupt changes that seem archaic nowadays”—“Very ambitious effort; for its day gave a fine understanding of Negro life and character; liked documentary quality; disliked jerkiness and over-elaborate plot”—“Parts of film extremely realistic, natural and moving; other parts ‘soap-opera’ in quality; but on the whole, impressive and poetic”—“A great film! and no more to be judged solely as a sociological report or treatise than the novels of Hardy or Twain; whatever its limitations, Vidor’s vision at the time was rich, positive, and I think sincere; an American painting done with strong strokes and leaving an unforgettable image in the mind; overall humanitarian tone; Melville-esque stature of leading character; but rhythmic structure seems weakened by short, title-separated sequences near end”—“Utterly true to its theme, ‘eternal conflict of flesh and spirit’; Vidor wisely avoided ambitious references to Negroes’ place in white society; his staying within the scope of his theme and the compassionate treatment and superb acting, together with amazing technical achievement and authentic detail, make it a film to remember; a tribute to the discernment of the programme committee”.

SPECIAL DISCUSSION GROUP ANNOUNCEMENT

The Childhood of Maxim Gorki by Mark Donskoi (U.S.S.R. 1938)

will be screened and discussed

Monday, February 15, 1954 – 8.15 p.m.

(PLACE: to be announced at the Feb. 8th Exhibition Meeting)

A Panel of specialists will give their views

on different aspects of the film.

This film, the first in the trilogy based on Maxim Gorki’s

autobiographies was exhibited in the Society’s 1950-51

Season and voted one of the best of that year. It is

being repeated to provide an introduction to the second

part, My Apprenticeship (Out in the World) which will be

shown at the regular Exhibition Meeting in March.

TORONTO FILM SOCIETY

DISCUSSION GRUOP

ADMIT 1: This form will admit 1 member of T.F.S. to –

The showing of The Childhood of Maxim Gorki on Feb. 15, 8:15 p.m.

A panel of specialists will comment on various aspect of the film:

…..The film as an adaptation (historical and literary background)

…..Its human and folk qualities

…..Its artistic and technical aspects

MAXIM GORKI 1868-1936

ALEKSYEI MARSIMOVITCH PYESHOKOF (pseudonym MAXIM GORKI), the last of the great literary figures of the pre-revolutionary era was born in 1868. The amazing story of his own life is told in his autobiographical series: Childhood (1913), Among Strangers (1915), My Universities (1923), Recollections (1924). (The first three were filmed in the late ‘thirties by Mark Donskoi; the second in the trilogy was re-titled My Apprenticeship or Out in the World).

His father died when he was five; Gorki then went to live with his maternal grandparents. In the film, Childhood, we have the unforgettable portraits of his mean, brutal grandfather, and his wonderfully courageous and loving grandmother. When the old people became poor, the grandfather turned the young Gorki out of the house. He toiled at a multitude of odd jobs and was often out of work. He was in turn a bootmaker’s apprentice, a pantry boy on a Volga steamer, a night watchman and a worker in a cellar bakery. He somehow scraped together an education and began to publish short stories; after this period, shortly before the first World War, he turned to long problems of society and to the drama. In 1902 he was elected an honorary member of the Academy of Sciences but his election was annulled by the government. After the relaxation of State censorship in 1905 he was able to found the literary periodical called Knowledge. At the first Congress of Soviet Writers in 1934 Maxim Gorki played a prominent part. He died in 1936.

Reference: Russian Literature from Pushkin to the Present Day by Richard Hare

Leave a Reply