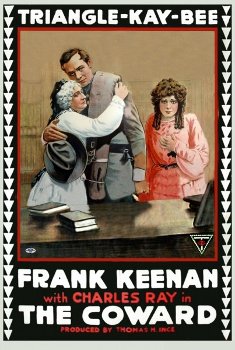

The Coward (1915)

By Toronto Film Society on November 21, 2017

Toronto Film Society presented The Coward (1915) on Monday, November 1, 1965 as part of the Season 18 Monday Evening Silent Film Series, Programme 1.

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

(Main Auditorium, UNITARIAN CHURCH, 175 St. Clair West)

Programme No. 1

Monday November 1, 1965

8:30 pm

The Innocent Fair (1915; 1963)

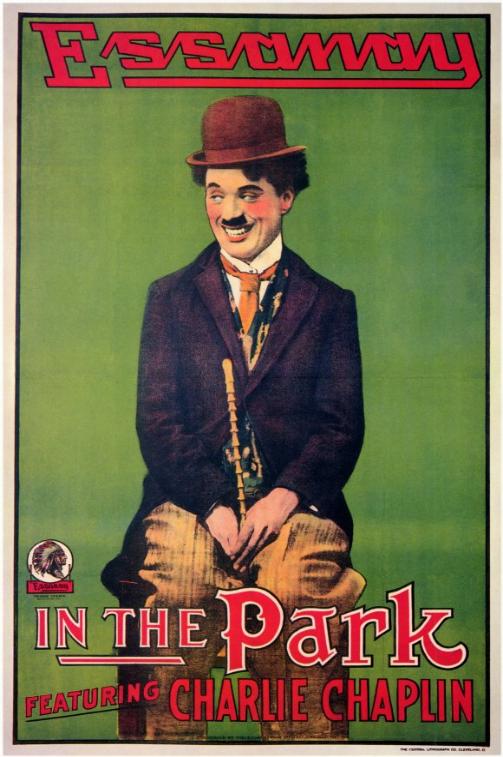

Charles Chaplin in In the Park (1915) [substituted with The Woman]

Intermission

The Life of an American Fireman (1903)

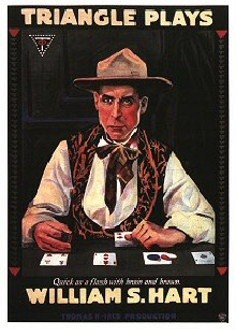

William S. Hart in Keno Bates, Liar [The Last Card] (1915)

Charles Ray in The Coward (1915)

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

1915 – FIFTY YEARS AGO

As you will notice, all but one of tonight’s films come to us directly or indirectly from the year 1915. What was it like in that year? What were we doing fifty years ago? What was going on in the world?

The most obvious thing going on was World War I (as we now call it; then it was just “the War” or “the European War”). It was the year of the fighting in the Dardanelles and Gallipoli. Canada was at war; the United States was not–though the sinking of the Lusitania on May 7 (a man-made disaster comparable to that of the Titanic) gave Americans to wonder whether neutrality was sufficient.

But even for Canadians the War was “over there”; and for most North Americans life was here. People were working and shopping and reading and singing and dancing and going to shows, as people always do. They were reading “Old Judge Priest” by Irvin S. Cobb, “The Genius” by Theodore Dreiser, “Ruggles of Red Gap” by Harry Leon Wilson, “The Way of an Eagle” by Ethel M. Dell. They were singing such popular tunes as “Along the Rocky Road to Dublin”, “Down Among the Sheltering Palms”, “Canadian Capers”, “Babes in the Woods”, “How’d you like to Spoon with me?”, “I Didn’t Raise my Boy to be a Soldier”, “It’s Tulip Time in Holland”, “I Want to be Loved like the Girls on the Film”, “Keep the Home Fires Burning”, “Memories”, “M-O-T-H-E-R”, “The Keystone Glide”, “The Old Grey mare”, “Pack Up Your Troubles”, “I’d Rather See a Movie with the Man I Love”, “Ragging the Scale”, “The Sunshine of Your Smile”, “Those Charlie Chaplin Feet”, “Take Me to the Midnight Cakewalk”, “So Long Letty” et mult. al.

Among the top films stars were Mary Pickford, Marguerite Clark, Theda Bara, Pearl White, Francis X. Bushman & Beverly Bayne, J. Warren Kerrigan, Anita Stewart and William Farnum. A columnist in Photoplay Magazine quipped, “I can see a better show in the back row any Saturday night than you ever get on the screen”, which proves that some things haven’t changed in fifty years. The big event of the movie world was D.W. Griffith’s The Birth of a Nation, which made an indelible impact upon both film history and American life. Following its New York success in March, twelve road showings of the film swept the continent and broke all box-office records. (In Toronto it played at the “Alexandra” from Sept 20 to Oct 9, and returned for Christmas week).

Visitors to New York could see such Broadway shows as “Common Clay”, “The Unchastened Woman”, “Potash and Perlmutter in Society”, “The Blue Paradise”, “The Princess Pat”, “Alone at Last” and “Hip-Hip-Hooray”.

Visitors to California had a choice of two big Fairs: the Panama-California Exposition in San Diego, and the Panama-Pacific Exposition in San Francisco (see page 4).

Canada was drying up. Alberta and Saskatchewan both introduced Prohibition (no connection with the disastrous flood in Edmonton only four weeks earlier); and the Ontario liquor License Act was passed, creating the Board of Commissioners, with the Ontario Temperance Act coming along the following year.

Other news items that year: May 6: Toronto’s Princess Theatre burned down, Sept 29: “Human voice transmitted by telephone from Washington to San Francisco” (but telephone communication between Toronto and San Francisco had been established the previous May 29). Oct 12: Nurse Edith Cavell was shot by the Germans. Nov 12: Winston Churchill resigned from the British Cabinet to join the Army in France. Dec 28: 121,973 Canadian troops have crossed the Atlantic without loss.

The Mayor of Toronto in 1915 was T.L. Church.

But let’s put ourselves into the mood for tonight’s program by glancing over a copy of The Globe (not yet “and Mail“) for exactly fifty years ago today: Monday, November 1, 1915 (and you may skip all this if it bores you):

The banner headlines read: “FURIOUS GERMAN ATTACKS ON THE WESTERN FRONTS – Land And Sea Forces Are Active in the Balkan Campaign”. Most of the front page is devoted to War news. Also featured heavily on the front page, however, is the death of the last surviving Father of Confederation: “Sir Charles Tupper Gone to His Reward”.

The “Book of the Day” column on the editorial page reviews “In Times Like These” by Nellie McClung, a book of essays.

Turning to the Sports page, we find the headline across the top of the page: “Roach-Toronto Settlement – O.R.F.U. Senior Series tied – Argos and Tigers win”.

Turning to the theatrical page, we learn that “The White Feather” (“the return of last year’s stupendous hit”) is opening tonight at the Alxandra (“No true Britisher, no loyal Canadian can afford to say that he has not seen tis play!”), with Al Jolson in “Dancing Around” advertised for next week. “Bringing Up Father” is at the Grand Opera House. The headliner at Sheas is Lulu Glaser, and the program includes “the Kinetograph, with New Features”. At the Gayety Burlesque: Sam Howe and his Kissing Girls, with beautiful Florence Mills and dainty Eva Mull”. There was more vaudeville at the Hippodrome (in City Hall Square) (mats 10 & 15⊄, eves 10, 15 & 25⊄), and “high class vaudevill” at Loew’s Yonge Street Theatre (at similar prices). (The vaudeville programs all include “film attractions”; but movie houses seldom advertised in The Globe in 1915, the exceptions being the occasional Mary Pickford film, or a Chaplin short or a serial in vaudeville bills, and of course the rare roadshow such as The Birth of a Nation or Geraldine Farrar in Carmen which played at Massey Hall the week of Nov 29 – “The World’s Greatest Photo-Dramatic Reproduction of the Opera”, with a Symphony Orchestra of twenty). We also learn that there is to be a piano recital on Wednesday by Ernest Seitz; and already the paper is advertising Paderewski at Massey Hall on Nov 22. (The Boston Opera Co and the Anna Pavlova Ballet Russe had paid a joint visit to Toronto two weeks earlier).

Let’s look at some of the other advertisements. Inevitably there’s “Children Cry for Fletcher’s Castoria”. An ad for Remington Typewriter is proudly headed: “International Novice Championship Typewriter Contest (in New York) won by Miss Hortense S. Stollnitz, operating a Model 10 Remington Typewriter” – she wrote 114 words per minute for 15 minutes, a world’s record for novices. (Whatever happened to Miss Hortense S. Stollnitz?)

The Robert Simpson Company Limited offers “A Dailly Bulletin for Buyers” which we can’t resist quoting at length:

Whit as the first snowflakes are the new hats and toques that we have just taken from the boxes in which they journeyed from new York. A vogue for white–both for suits and for millinery–is an assured fact in that city, and these dainty examples which are shown in one of our Yonge Street windows is an advance guard of further arrivals. Of hatters’ plush, of velvet, with trimmings of the inevitable fur, whether it be ermine, beaver, Kolinsky or what not–some with garniture of a flat velvet rose or two, in vivid colors: one with a fluffy fur pom-pom poised on the edge of the crown, while around the base is knotted a narrow white band, edged with silver–you will see them with all their attractions this morning. One pretty set consists of a close-fitting toque of white velvet banded with two narrow strips of very dark coney and with two saucy little pom-poms at the side and a muffler of the velvet, which is edged with fur and ties coquettishly at the chin. This set is priced $17.50.

Less poetically, as befits its “Tuesday Bargain list”, Eaton’s offers:

Misses’ coats; modeled on one of the newest Winter styles, with fur chin chin collar, pleated back and flare skirt and wide belt running from sides across front. Materials are navy, light, dark grey chinchilla and black Whitney cloth…

Women’s Patent Leather Buttoned Boots; dull calf tops, Cuban heels…

Men’s Overcoats, Tuesday, $10.00. A manufacturer’s surplus lot of 90 coats offered at dollars less than usual price. They are young men’s single breasted Chesterfields with buttons showing through, smartly shaped lapels and wide wale serge lining. The materials are warm tweed coatings in choice of 8 patterns, several shades of gray and brown and a few in olive shade. Two-tone effects, diagonals and stripes….

A few items from Eaton’s food department:

5000 lbs Choice Round Steak, special, 16⊄ b. Round End Rump Roast of Beef, 17⊄ lb. Thick Rib Roast Beef, 15⊄ lb. Loin of Spring Lamb, 17⊄ lb. Smoked Finnan Haddie, 10⊄ lb… 5000 tins finest canned tomatoes, 3 tins 20⊄ (limit 6 tins to customer)…

Murray-Kay, Ltd., advertised:

Women’s Cashmere Hose, 35⊄ a pair, 3 for $1.00.

Turnbull’s Underwear for Women: $1.35 each.

Ad for Canadian Northern Railway: “Through service Toronto to Winnipeg now in effect, via Parry Sound, Sudbury, Port Arthur and For William. Connections at Winnipeg Union Station for Edmonton, Calgary, Prince Albert, Saskatoon, Regina, Brandon and all important points in Western Canada and the Pacific Coast. Leave Toronto 10.45 pm Monday, Wednesday and Friday”.

Ad for the Santa Fe Railway: “DECEMBER END TWO FAIRS FOR ONE FARE. GO NOW. San Francisco Exposition closes Dec 4. Sand Diego Exposition closes Dec 31. Low-fare excursion tickets on sale until Nov 30–good for return until Dec 31.

Which leads us to the first item on tonight’s program………

* * *

The Innocent Fair (1963) (20 minutes)

Produced by Television Station KPIX, San Francisco

Written and produced by Ray Hubbard, with the assistance of Julius S. Rodman Associates Documentary Film Division and James M. Leonard, Hall of the Golden City, San Francisco. Narrated by Walter Johnson

The Museum of Modern Art Film Library supplementary catalogue (April 165) provides the following program notes for this television documentary:

To affirm and celebrate its rebirth from the ashes of the earthquake and fire of 1906, San Francisco planned a great World’s Fair, the Panama Pacific International Exposition. The Fair did not become a reality until 1915, by which time clouds were gathering which have never since quite lfited, but at this last moment it testified with surging power to the 19th century belief in the eternal betterment and progress of the human race. The whole new city and all its inhabitants become part of the unfolding pageant. Here, side by side and with no discernible conflict, are the Palace of Machinery and the Palace of ARt and Culture. Here are those new marvels, the automobile and the airplane–and the motion picture, whose newly famous celebrities, Roscoe Arbuckle, Mabel Normand, and Charles Chaplin make modest appearances as spectator-participants. All this was meticulously recorded on miles of film, whose pristine negative, intact and for the most part beautifully preserved, had been gathering dust throughout the intervening years until it was unearthed by an enterprising television producer. The resulting brilliantly conceived film is implicit with both irony and nostalgia: “we would never be so young, so innocent, again”. It is also a significant example of the possibilities of local television programming.

* * *

In the Park (approx 15 minutes)

Written and produced by Charles Chaplin

Photographed by Rollie Totheroh

Released by Essanay, March 18, 1915 (1 reel)

(Musical sound track provided for this print by Zodiac Films, Montreal)

Players: Charles Chaplin, Edna Purviance, Leo White (as the lover), Lloyd Bacon (as the tramp), Bud Jamison.

In 1913 Charles Chaplin was touring the United Stats in “A Night in an English Music Hall” when Mack Sennett signed him to a year’s contract to make films for Keystone for $150 a week, three times his current salary. He arrived in Hollywood in December of that year, at the age of 24. His first film, Making a Living, was released in February, 1914. By the end of that year he had appeared in 34 sorts and one feature (Tillie’s Punctured Romance) and was directing his own films, and had so quickly and enthusiastically caught on with the public that when his contract expired, the Essanay Company snatched him away from Sennett with a year’s contract that paid him $1250 a week.

Thus, for the year 1915 all Chaplin’s films were made for and released by Essanay. The first one was made in Essanay’s Chicago studios and was appropriately entitled His First Job. The next five were made at the Essanay studios in Niles, California, near San Francisco: A Night Out (in which Edna Purviance appeared in her first film as his leading lady, which she continued to be exclusively until 1923), The Champion, In the Park, The Jitney Elopement and The Tramp. (Presumably it was while he was working at Niles that he paid the visit to the San Francisco Fair that figures in The Innocent Fair). Thereafter he made all his films in Los Angeles, beginning with By the Sea.

By 1915 the Charlie Chaplin craze was in full swing, comparable to that of the Beatles. Children everywhere imitated his walk; there were Charlie Chaplin Impersonation contests, and for 25⊄ you could buy a Charlie Chaplin kit consisting of black derby hat and stick-on moustache (“Great for masquerades, celebrations and parades. BE THE FIRST”). There were Charlie Chaplin comic books; Charlie Chaplin jokes; Charlie Chaplin games and tricks; Charlie Chaplin Squirt Rings and other novelties; Charlie Chaplin postcards and candy-bar cards; and in 1915 alone there were at least half-a-dozen (some say twenty) Charlie Chaplin songs published (“Charlie Chaplin, the Funniest of Them All”, “Funny Charlie Chaplin”, “Charlie Chaplin Walk”, “Charlie Chaplin Glide”, and one that actually did become popular: “Those Charlie Chaplin Feet”); and of course, countless magazine articles, interviews and pictures.

No wonder that when his contract with Essanay ran out, the Mutual Film Company signed him up for a salary of$10,000 a week, plus a bonus for just signing the contract. (Looking ahead: The twelve films he was pledged to produce for Mutual in 1916 actually took him 18 months to complete, but they are now considered the vintage Chaplin shorts. In a 1916 issue of Harper’s Weekly, the distinguished American actress, Minnie Maddern Fiske, wrote an article called “The Art of Charles Chaplin”, in which she hailed “the young English buffoon, Charles Chaplin, as an extraordinary artist, as well as a comic genius”–thus making it okay for cultured people to admit they liked Chaplin. When his contract with Mutual ended, Chaplin set up his own company, releasing at first through First National, and thereafter through the company he had helped to found, United Artists; since when he has produced only feature-length films).

* * *

The Life of an American Fireman (6 minutes)

Produced by the Edison Company

Directed by Edwin S. Porter

Before we turn to the two fiction films that were made in 1915, it is only fair to give you an idea of how far films had progressed in a dozen short years. (Has television made a comparable advance since 1953?)

Unfortunately we haven’t time to be equally fair to The Life of an American Fireman by showing you representative samples of what regular films were like up to and even after this little film was made in 1903, so that you could appreciate what a giant step forward it was in its time.

Movies in those days were the property of penny arcades, who either presented them in a curtained-off section at the back, or were concentrating on movies entirely; in either case presenting for 10⊄ a program of short films, ech film being about a minute long, more or less. Their subject matter ranged from actualities to staged incidents, and were purchased from the film-makers’ catalogues which classified them as “Views”, “News Events” (either real or faked), “Vaudeville Turns”, “Incidents”, “Magical Pictures”, and short comedies (in one scene or “take” only) including various popular series such as Happy Hooligan, Weary Willie, Grandma and Granpa and The Rube.

The first films to tell a story in a series of consecutive scenes were made in France by George Meliés, whose fantasies–beginning in 1900 with Cinderella and including that films ociety classic, A Trip to the Moon (1902)–were imported and became very popular with American audiences. They were also a revelation to a certain cameraman in the employ of Thomas Edison’s film company: Edwin S. Porter, who analysed them and noted that they were made up of not one but several camera shots, joined together to illustrate a story; and from this he hit upon the revolutionary idea that one might also make stories by cutting and joining, in a determined order, scenes that had already been shot. In short, he invented film editing.

Given the go-ahead by his employers, he looked through the material on file (“stock shots”) and decided to build his story around fire-fighters,–always a sure-fire subject. (Note that whereas Meliés’ films were all fantasies, Porter’s film pictured everyday life). Around this material he concocted a naively simple story of a mother and child caught in a burning building and rescued by the fire department. This required staging a few additional shots; after which he assembled all his shots—real and staged–into a logical order, and the result was the first narrative film in American movie history).

(Porter followed this film with the first movie adaptation of a standard fictional work: Uncle Tom’s Cabin‘ and before the year was over he was to make the now-classic The Great Train Robbery. The latter was a great advance on The Life of an American Fireman, but obviously it was not, as is sometimes claimed, the first narrative film).

The Edison Catalogue of 1903 included the complete scenario of The Life of an American Fireman, and this has been reproduced in full in Louis Jacobs’ book “The Rise of the American Film” (pp 38-41) which you can find in the Public Library (and from which we have cribbed most of the foregoing material). Here, as a sampler, is the first scene in full, followed by the names (without the description) of the other six scenes:

Scene 1: THE FIREMAN’S VISION OF AN IMPERILED WOMAN AND CHILD

The fire chief is seated at his office desk. He has just finished reading his evening paper and has fallen asleep. The rays of an incandescent light rest upon his features with a subdued light, yet leaving his figure strongly silhouetted against the walls of his office. The fire chief is dreaming, and the vision of his dream appears in a circular portrait on the wall. It is a mother putting her baby to bed, and the impression is that he dreams of his own wife and child. He suddenly awakens and paces the floor in a nervous stat of mind, doubtless thinking of the various people who may be in danger from fire at the moment.

Here we dissolve the picture to the second scene:

Scene 2: CLOSE VIEW OF A NEW YORK FIRE ALARM BOX

(Students of cinema history take note of this early use of a close-up)

Scene 3: SLEEPING QUARTERS

Scene 4: INTERIOR OF ENGINE HOUSE

Scene 5: APPARATUS LEAVING ENGINE HOUSE

Scene 6: OFF TO THE FIRE

(“In this scene we present the best fire run ever shown. Almost the entire fire department of the large city of Newark, New Jersey, was placed at our disposal… Great clouds of smoke pour from the stacks of the engines, thus giving an impression of genuineness to the entire series”).

Scene 7: ARRIVAL AT THE FIRE

(Note that this final scene actually consists of three different camera shots, thus establishing for the first time that “scene” and “shot” need not be synonymous. The description concludes: “The child…upon seeing its mother, rushes to her and is clasped in her arms, thus making a most realistic and touching ending of the series”).

Don’t laugh. From this little film grew all Hollywood. Edwin S. Porter deserves his important niche in the cinema’s Hall of Fame.

* * *

After that flashback into the past, we return to the present: A.D.1915. In the intervening years Porter’s pioneering creative genius had petered out; the next rash of technical innovations began appearing soon after D.W. Griffith became a director at Biograph in 1908. Somebody had to be the first to think of such “obvious” devices as fade-outs, flashbacks, close-ups, and to realize that the camera need not be limited to the limitations of the stage but had as much freedom as the novelist’s pen; and that man was Griffith.

The next advance came when European filmmakers proved that films need not all be shorts but could be as long as any stage play. The success at the North American box-offices of such spectacular blockbusters as Cabiria and Quo Vadis, imported from Italy, and Sarah Bernhardt’s Queen Elizabeth, led to a revolution comparable to the one caused by the introduction of sound in the late 1920’s: the establishment of the “feature” film (as opposed to shorts) as the norm. By 1915 the feature film is obviously here to stay.

Furthermore, film acting has become a respectable occupation for proud stage actors; the incredibly high salaries offered to the big stage stars proved an inducement stronger than pride. 1915 was the big year when Hollywood lured so many stage stars to the screen that Broadway was almost denuded of actors, while film, having long since emerged from the penny arcades, were themselves being presented in Broadway legitimate theatres, complete with symphony orchestras. The Birth of a Nation (in 12 reels, the longest American film to date) even charged an unprecedented $2 top admission, and also proved beyond a doubt that movies had come of age.

Our three 1915 films tonight were hardly in that class (though our feature did have a Broadway opening, at the Knickerbocker), but they were all outstanding in their particular fields.

* * *

Keno Bates, Liar (The Last Card)

Produced by the W.H. Production Co.

Directed by Wm S Hart and Cliff Smith

Supervised by Thomas H. Ince

Written by Thomas H. Ince and J.G. Hawks

Photographed by Joseph August

Players: William S. Hart, Louise Glaum

William S. Hart (1870-1946) spent his boyhood in the Western plains and never lost his love for the West. In later years, after he had been a stage actor for many years, he was so appalled by the inaccuracies of the usual movie Western that he went into pictures with the deliberate intention of putting onto the screen the real West. Thomas Ince, a former stage actor who had drifted into films in 1910 and become a director, was by this time (summer of 1914) the head of his own big studio at Inceville, just outside of Hollywood. He and Hart had been friends in their stage days, so Hart applied to him and was put under contract. Hart’s first assignments were supporting roles in two shorts starring a Tom Chatterton; thereafter he himself was starred, at first only in two-reelers. (The swing to feature pictures was not yet complete; many short films, mostly westerns and comedies, were still being produced as “added attractions”). Hart’s output in 1915 included a few features but were mostly shorts, of which the last seems to have been Keno Bates, Liar,–after which he devoted himself exclusively to features. Hart directed most of his own films, though Ince long continued to take nominal credit.

Hart moved with Ince to Paramount late in 1917 and remained there till 1924. (The Hart film we showed last year The Toll Gate, was made in 1920, five years after Keno Bates). In 1925 he made Tumbleweeds for United Artists, then retired from the screen for the rest of his life. (See last year’s notes–Feb 8, 1965–for more detailed information about Hart; or better still, read the chapter on Hart in “The Western” by Fenin and Everson).

With the rise of Hart’s popularity, many of his earlier films were reissued to cash in on his box-office appeal, frequently with new titles to fool people into thinking they were getting a new film. Keno Bates, Liar was re-released as The Last Card, and it is apparently from one of these prints that this 16mm print was made.

* * *

The Coward

Written and produced by Thomas H. Ince

Scenario By C. Gardner Sullivan

Directed by Reginald Barker

Supervised by Thomas H. Ince

Released November 14, 1915

Copyrighted by Triangle Film Corp. in 6 reels,

(but “apparently it was customary to reduce

prints to 5 reels for general release”)

Players: Frank Keenan (as Colonel Winslow)

Charles Ray (as Frank Winslow)

Gertrude Claire, Margaret, Gibson, Nick Cogley, Charles K. French

It may seem inconsistent that in a program featuring the year 1915 our longest film should be a “costume drama” rather than a picture of contemporary life. But it is worth remembering that in 1915 the American Civil War had ended only fifty years before, the same length of time that separates us from this film, and that for many people who saw this film when it first came out, the Civil War was as much a personal memory as World War I is for many people today. And just as there may conceivably be people watching The Coward in our audience tonight who also saw it originally back in 1915, so these people would have seen it in an audience that must have included people who themselves had taken part in the Civil War. Thus our 1915 film enables us to reach back a whole century.

As a contemporary document, of course, its choice of a Civil War subject reflects the current popularity of The Birth of a Nation; and in the film itself we also catch a glimpse of contemporary attitudes which make 1915 seem a very long way off. As Edward Wagenknecht has pointed out (“The Movies in the Age of Innocence”), the father’s “behavior is outrageously self-righteous throughout, yet the audience is evidently expected to sympathize with him”. Audiences evidently did, for the picture was a great success, and even several years later people were looking back to it as a memorable screen highlight.

In the late ‘teens and early ‘twenties Charles Ray was to become one of the biggest box-office stars of the time, and it is as a Charles Ray film that we are showing The Coward; but in fact the actual star of the film, so far as contemporary billing went, was not Charles Ray but Frank Keenan, an outstanding stage actor who had been brought to Hollywood earlier that year on the strength of his theatrical reputation. Indeed, it has been reported that when he was engaged for this film he received the highest salary ever paid to a male star up to that time, and accurate or not the report is at least an indication of his contemporary reputation. But whatever Frank Keenan may have been on the stage, both before and afterwards (see page 11), it was the film-trained Charles Ray who became the big screen star, and whose performance still stands up today.

CHARLES RAY was born in Jackson, Illinois, on March 15, 1891. When he was 16 his family moved to a small ranch in Arizona, and then to Los Angeles. His acting career started in amateur plays staged in his home town back yard; his professional career included some musical comedy. But a bad season on the stage drove him to try for work in the films; and on December 12, 1912, he began work at Inceville, arriving at the fortuitous time when Ince’s leading man, Harold Lockwood, had just left and Ince needed somebody to replace him.

Ray’s first prominent role was in a two-reeler, The Favorite Son, directed by Francis Ford (John’s brother), released Feb 7, 1913. But like any actor in a stock company, Ray played just about everything–“heavies” and character parts as well as juvenile leads. This went on for about three years till his role and performance in The Coward attracted public attention to himself; and soon afterwards it was “Charles Ray in…” In 1917 Thomas Ince withdrew from Triangle Pictures and signed up with Paramount-Artcraft, bringing with him the players and crew under contract with him, including both hart and Ray. By 1920 Charles Ray was one of Paramount’s most valuable properties. A 1921 popularity contest revealed that the two most popular male stars at the box-office were Wallace Reid and Charles Ray.

Although in the films that immediately followed The Coward (one of which, inevitably, was another Civil War story called The Deserter) Ray continued to play the weakling son of a wealthy family who overcomes thishandicap to Become a Man (Ince was apparently fond of “soul-fight” pictures), he was soon specializing in the role he was to play innumerable times until (and because) he had it polished to perfection: the unsophisticated country boy, “the bashful, charming, naive and boyish country bumpkin who aspired to become a hero”. (“We tried Ray as other types” says Adolph Zukor, “but the country boy was the only one he could play”). As Edward Wagenknecht puts it: “In view of the large number of girls who have functioned successfully as ingénues, it is interesting that Ray was the only male who ever had as important career as whatever it is that corresponds among men to an ingénue, though it is possible that both Robert Harron and Richard Barthelmess might have companioned him if Griffith had not rescued them by casting them in more varied roles. Barthelmess’s supberb Tol’able David (1921) was, in a way, a kind of Charles Ray film… As it was, however, Ray became the screen’s barefoot boy par excellence.”.

But Ray played the barefoot boy only on the screen. Offscreen he lived in a style befitting his princely salary: a palatial home in Beverly Hills with (it was said) a fifteen thousand dollar dining-room table, an enormous turquoise bathtub, liveried servants, etc etc; his wife was alleged never to wear the same gown twice.

Unfortunately it didn’t last. In 1920 he left Paramount to form his own production company, releasing at first through First National and later through United Artists. At least one of these films, The Old Swimmin’ Hole (1921) is remembered as Ray’s best films, and also deserves some kind of historian’s award for having attempted to dispense entirely with subtitles–anticipating by nearly four years Murnau’s more famous The Last Laugh.

But the 1921 popularity contest found Charles Ray at his zenith. Box-office figures soon began hinting a growing public satiety with the naive country boy (especially as the 1920’s were finding a new type of screen idol in the sexy Valentino), and in 1923, in a valiant attempt to break with type, Ray sank a fortune into a big historical picture, The Courtship of Miles Standish, with himself as John Alden. Apparently it was not a very good film, and certainly not what the public wanted to see Charles Ray in, and it completely died at te box-office–and Ray lost everything, palatial home and all.

Hastily he reverted to type and made a few more films in the old small-town formula for minor companies; but it was too late. Charles Ray as a star was finished. As an actor he continued for many years and managed to play varied roles, including sophisticated, evening-dress parts; but again, it was too late. He could never entirely shed the mannerisms he had acquired in several years of polishing to perfection the country-boy roles that had been his speciality. His roles became smaller and smaller until they were only bit parts. He also tried his hand at writing; and in the early ‘forties he was involved in promoting another film producing company, and in 1942 he again found himself broke. A long illness ended with his death in the Cedars of Lebanon Hospital on November 23, 1943, in his 53rd year.

The following is not a complete Charles Ray filmography but is merely a chornological list of all the titles we came across in our search for biographical material:

1913: The Favorite Son

1915: The Lure of Women; The Coward

1916: The Deserter; Honor They Name; Home

1917: Skinner’s Dress Suit; His Father’s Son; The Pinch Hitter; The Clodhopper; Sudden Jim; His Mother’s Boy

1918: The Hired Man; Playing the Game; The Claws of the Hun; The Law of the North; String Beans

1919: The Sheriff’s Son; Greased Lightning; The Busher; Hayfoot, Strawfoot; Bill Henry; The Egg Crate Wallop; Crooked Straight

1920: Paris Green; Homer Comes Home; 45 Minutes from Broadway; The Village Sleuth; An Old Fashioned Boy

1921: The Old Swimin’ Hole

1922: The Barnstormer; A Tailor Made Man

1923: The Girl I Loved; The Courtship of Miles Standish

1925: Percy; Some Pun’kins; Sweet Adeline

1927: Getting Gertie’s Garter; Vanity

1928: The Garden of Eden

1934: Ladies Should Listen

1936: Hollywood Boulevard

1940: A Little Bit of Heaven

At least two Charles Ray films are available to 8mm collectors: The Busher (1919)–with Colleen Moore and John Gilbert in supporting roles–and the post-Standish Sweet Adeline (1925). Both are charming films, particularly the former which was made in his heyday; but even the latter is rather fun, in its unabashedly corny way. Admittedly Ray gives the same performance in both films; but it’s a good performance.

FRANK KEENAN was born in Dubuque, Iowa, on April 8, 1858, and made his stage debut in Boston in 1880. By the 20th Century he was a successful star on Broadway–he was the original Jack Rance in Belasco’s The Girl of the Golden West (1905) and appeared in William DeMille’s The Warrens of Virginia (1907), also directed by Belasco, with a cast that included Cecil DeMille and little Mary Pickford. He was brought to the screen in 1915 by Universal in The Long Chance, but soon moved to the Ince studios where in addition to The Coward he also starred in The Thoroughbred, The Crab and others. Later he went over to Pathé and made Loaded Dice, The Bells and The Defender. Around 1919 he went into production for himself, but evidently it wasn’t very successful for in 1920 we find him back on the stage in “John Ferguson”. In 1923 he was on Broadway with Judith Anderson in “Peter Weston”. He died February 24, 1929, in his 71st year.

Notes by Fraser Macdonald

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

OUR NEXT ATTRACTION: RUDOLPH VALENTINO in The Son of the Shiek (1926): MON DEC 6

You may also like...

-

News

Frances Blau

Toronto Film Society | February 27, 2024On Monday, February 26th, 2024, Toronto Film Society lost longtime friend, supporter, and board member Frances Blau. Known for her sense of humour, her love of film, her generosity,...

-

Special Events

Monday Evening Film Noir Double Bill at the Paradise Theatre

Toronto Film Society | July 8, 2024The Toronto Film Society presents a film-noir double feature at one low price! The Window (1949) in a double bill with Black Angel (1946) at the Paradise Theatre on Monday, August...

Programming

Virtual Saturday Night at the Movies

Toronto Film Society | July 20, 2024Toronto Film Society is back in the theatre! However, we’re still pleased to continue to bring you films straight to your home! Beginning Season 73 until now we have...

4-

Toronto Film Society | July 8, 2024

Toronto Film Society | July 8, 2024

Monday Evening Film Noir Double Bill at the Paradise Theatre

-

Toronto Film Society | November 6, 2022

Toronto Film Society | November 6, 2022

-

Toronto Film Society | August 1, 2023

Toronto Film Society | August 1, 2023

Donate to Toronto Film Society – We’re now a Registered Charity!

-

Copyright © 2017 Toronto Film Society.

Leave a Reply