The Mark of Zorro (1920)

Toronto Film Society presented The Mark of Zorro (1920) on Monday, October 26, 1964 as part of the Season 17 Monday Evening Silent Film Series, Programme 1.

Programme No. 1

Monday, October 26, 1964

Charles Chaplin in The Idle Class (1921) (2 reels)

Douglas Fairbanks in The Mask of Zorro (1920) (8 reels)

It is only a coincidence that in the two films chosen for tonight’s programme, both Chaplin and Fairbanks play dual roles; but it is not inappropriate that these two stars should share a program, for in real life they were close personal friends as well as business partners, being co-founders (with Mary Pickford and D.W. Griffith) of United Artists. The story of their first meeting and the birth of their lifelong friendship is told (accurately or otherwise) in Douglas Fairbanks: The Fourth Musketeer by Ralph Hancock and Letitia Fairbanks. The incident occurred in 1916, not long after Fairbanks had begun making films:

One day Chaplin happened to be passing a Hollywood picture theatre and paused to look at some posters of Fairbanks which adorned the entrance. When Chaplin had looked them all over, he turned to an unobtrusive young man who had been watching him out of the corner of his eye.

“Have you seen this show?” Chaplin asked.

“Sure”, replied the young man.

“Any good?” asked Chaplin.

“Why, he’s the best in the business. He’s a scream! Never laughed so much at anyone in all my life”.

“Is he as good as Chaplin?” ventured Chaplin, hopefully.

“As good as Chaplin!” The young man’s scorn was superb. “Why, this Fairbanks person has got that Chaplin person looking like a gloom. They’re not in the same class. Fairbanks is funny. I’m sorry you asked me, I feel so strongly about it”.

Chaplin drew himself up, looked at the fellow sternly, and said, “I’m Chaplin”.

“I know you are”, said the young man cheerfully. “I’m Fairbanks”.

The Idle Class

Written and directed by Charles Chaplin

Photographed by Rollie Totheroh

Released by First National, Sept 25, 1921

Cast:

The absent-minded husband

The wife

The angry father

Charles Chaplin

Edna Purviance

Mack Swain

Chaplin’s first feature-length film, The Kid (1920), was followed by two more short comedies, The Idle Class and Pay Day, after which he abandoned two-reelers forever, devoting himself thereafter exclusively to features.

Of purely incidental interest is the fact that among the extras in the cast, playing maids, are Lita Grey and her mother. Lita Grey, then only thirteen, married Chaplin three years later and became the mother of Charles Jr and Sydney.

The Mark of Zorro

Produced by Fairbanks-United Artists

Directed by Fred Niblo

Adapted by Douglas Fairbanks from “The Curse of Capistrano” by Johnston McCulley

Released by United Artists in November, 1920

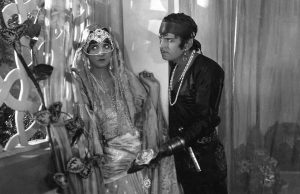

Cast:

Sergeant Pedro

Don Carlos Pulido

His wife, Doña Catalina

Lolita

Captain Juan Ramón

Governor Alvarado

Fray Felipe

Dn Alejandro

A peon

Noah Beery

Charles Hill Mailes

Claire McDowell

Marguerite de la Motte

Robert McKim

George Periolat

Walt Whitman

Sydney De Grey

Charles Stevens

This film is the original Mark of Zorro, the immediate ancestor of all subsequent screen and TV versions, including Airbanks’ own sequel, Don Q, Son of Zorro (1925). True, it was not an original screen play; but its literary antecedent was simply a magazine short story which would have vanished into the normal oblivion of all pulp fiction if Fairbanks had not chanced on it and created from it one of his most successful films. If Johnston McCulley or his estate has grown rich on royalties, it is all thanks to this Fairbanks film.

Incidental intelligence: “zorro” is the Spanish word for “fox”. Theh Spanish also have an expresssion: “hacerse uno el zorro”–roughly, “to play the fox with someone”–which means to pretend to be stupid.

And for your curiosity: it is said that Mary Pickford, who looked not unlike Marguerite de la Motte, actually doubled for her in the love scene.

* * *

“Douglas Fairbanks is generally regarded as the leading exponent of light comedy boys and young men of today. He has an ingratiating personality charged with health, directness, breeziness, and a certain patrician quality which contributes an attraction to any part he plays. He has been on the stage only nine years, yet in that time he has created a new role in New York on an average of at least once a year”. – from The American Stage of Today (published 1910)

It was as an important Broadway star that Douglas Fairbanks (1883-1939) was imported to Hollywood in 1915 to star in The Lamb, a screen adaptation of his stage success, “The New Henrietta”. Most imported stage stars proved duds on the silent screen, but Fairbanks was a hit from his very first film, and such a goldmine to the film company that in less than two years they were paying him a salary of $10,000 a week. He formed his own company, releasing his films at first through Famous Players-Lasky (Paramount), and after 1919 through the company he helped to form: United Artists.

From 1915 to the middle of 1920 he turned out a total of 29 films, most of them written by Anita Loos and directed by John Emerson, all of them following the forumla that had made his first films so popular. (Typical titles: Double Trouble, His Picture in the Papers, Reggie Mixes In, The Americano, Wild and Woolly, A Modern Musketeer, Mr Fix-it, He Comes up Smiling, A Knickerbocker Buckaroo and When the Clouds Roll By).

For his 30th film, however, he made a daring break from this safe and profitable formula and produced The Mask of Zorro, thereby launching a new Fairbanks era which lasted to the end of the 1920s, in which his name was associated with big costume pictures, painstakingly produced at a rate of less than one a year. (Eight such films in ten years, including Zorro; compare with the eleven films he turned out in 1916 alone).

For the story behind this changeover, we quote copiously from Chapter 14 of the aforementioned Douglas Fairbanks: The Fourth Musketeer (p.127 et seq.):

The year 1920 not only included the culmination of Doug’s romance in marriage to America’s sweetheart, but it also marked the biggest change in his screen character. Up until then, as we have seen, he had reflected the spirit of the times in his buoyant roles–the typical young American overcoming obstacles in athletic stunts to win the girl and live happily ever after–and his recent pictures had been good-natured satires, ribbing the social frivolities and poking fun at postwar neuroses.

But the Jazz Age and the Roaring Twenties were steadily gathering momentum. Escapism, accelerated by prohibition and bathtub gin, were altering the wholesome American pattern into a pseudo-sophistication that boasted bootleggers, flappers, speculations in the stockmarket, and compassionate marriage. Moreover, the social and political revolution following the blood lust of the war years made the present seem as insecure as the immediate past from which everyone was escaping. Kings were toppling from their thrones and the strict code of Victorian morality was being discarded. A smattering of Freud added to bootleg alcohol was liberating the American libido, and drunkenness, divorce, and a flaunting of sex were considered fashionable.

None of this was fertile ground for an actor who had been the symbol of integrity to youth, who had preached the doctrine of clean and honest living. It was a crucial point in his career and the future was already casting portentous shadows. As an opportunist with his finger on the pulse of his times, he may have known intuitively that an escape for escapism was needed; on the other hand, his decision may have been purely a matter of luck. Certainly he knew that his prestige at the box office was headed for a test when he decided to make a costume picture in a California setting of the 1850’s. Costume pictures were still considered poison at the box office, for exhibitors still remembered the colossal failure of D.W. Griffith’s Intolerance, released only four years before. Since then, no producer had been sufficiently foolhardy to risk capital on historical sagas which necessitated the spending of huge sums on costumes, sets, research and the numerous extras which made these spectacles authentic. Moreover, the public was entitled to its apathetic attitude toward them, since most of those that had been produced were robbed of their sense of reality by the self-conscious acting of the players who appeared generally as if they were made up for a fancy dress ball.

Robert Fairbanks came into Douglas’s office one morning with a copy of the pulp magazine All-Story Weekly. The issue was August 9, 1919, nearly a year old. The lead story in it was “The Curse of Capistrano” by Johnston McCulley. “Read it”, said Robert, pointing to the story. “It’s not bad once you get past the title”.

Robert’s deprecatory tone was calculated to make his brother take sufficient interest in the story to read it. He did and he was immediately enthusiastic about it and its picture possibilities. Thus, retitled The Mark of Zorro, Johnston McCulley’s story of early California days became Douglas Fairbanks’ daring plunge into a doubtful field.

Stripped down to the bare essentials of a fast-moving plot wherein Zorro (Douglas) avenges the wrongs of the Governor, an 1850-model dictator, the costumes served to dramatize the action. But it was in the dueling sequences that Douglas came into his own, when as Zorro he managed to leave his mark on his opponent, a “Z” cut with his sword into the face or shoulder. This, of course, was the mark of Zorro.

The picture was previewed at the Beverly Hills Hotel. When it was over the critics went away without much cheering and Douglas was left with a feeling of depression and failure.

By the time he and Mary Pickford arrived back at Pickfair he was in a restless mood. Pacing back and forth in the huge living room he kept mumbling over and over again, “I just don’t understand it. I thought Zorro was a great picture”.

“It is, darling”, Mary assured him. “Don’t let a few critics upset you”.

And Robert, who had accompanied them, assured his brother. “You wait and see, the public will go for it”.

The public did. The avalanche of fan mail and the river of gold that flowed into the box offices were proof that costumed escapades as Fairbanks made them could compete with anything the Jazz Age might dream up.

It was near the end of November, 1920, before The Mark of Zorro was released, and while Douglas waited anxiously for the public’s reaction, he made one more picture on the old safe-bet pattern. By the time this one, The Nut, was released in March, 1921, he was well aware that the public not only liked his costume piece but preferred it to anything he had ever done before. He had found his ultimate niche.

* * *

A highly trained athlete, Fairbanks did all his own acrobatics; he used neither trick photography nor doubles. But his films were fiction, not documentaries, and like a beautiful ace improved by make-up, truth can be enhanced by art. When Fairbanks, in the middle of a sword fight, leaps onto a table without even glancing at it, he owes his unflustered grace to the fact that the height of a comfortable Fairbanks leap has been ascertained by careful measurement, and the table legs have been sawn down till the table is the exact desired height. Hidden handholds were built into his sets at strategic spots, to make climbing easier. “Doug always received dozens of letters from irate mothers after such a picture” adds Ralph Hancock. “It is doubtful if any man has been responsible for more broken arms and legs”.

Notes by Fraser Macdonald

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

Our next meeting is MONDAY NOVEMBER 16 (three weeks from tonight). The subject will be GREAT ACTRESSES OF THE PAST and OPERA STARS IN FILMS, and the programme will consist of excerpts from the following films:

GABRIELLE REJANE (1857-1920) in Madame Sans-Gene (1911): Réjane was one of France’s leading comedy actresses in the latter part of the 19th Century, and Madame Sans-Gene was her outstanding role.

SARAH BERNHARDT (1845-1923) in Camille (1912): One of Bernhardt’s most famous roles transferred to screen. Lou Telegen plays Armand.

MINNIE MADDERN FISKE (1865-1932) in Vanity Fair (1915): One of the great actresses of the American stage, Mrs Fiske included Becky Sharp among her most successful roles. The film offers a glimpse of her stae interpretation.

ELEANORA DUSE (1859-1924) in Cenere (1916): Another of the big Italian superspectacles of that period, this film constituted Duse’s only screen appearance.

GERALDINE FARRAR (1882- ) in Carmen (1915): Directed by C.B. DeMille, with Wallace Reid as Don José, this film was one of the big hits of the year, and launched this celebrated opera star into a new career as a popular silent-screen actress.

MARY GARDEN (1877- ) in Thais (1916): Well, at least it’s a curiosity.

ENRICO CARUSO (1873-1921) in My Cousin (1919): This laid a colossal egg at the box-office, thus nipping in the bud Caruso’s potential career as a delightful screen personality.

Leave a Reply