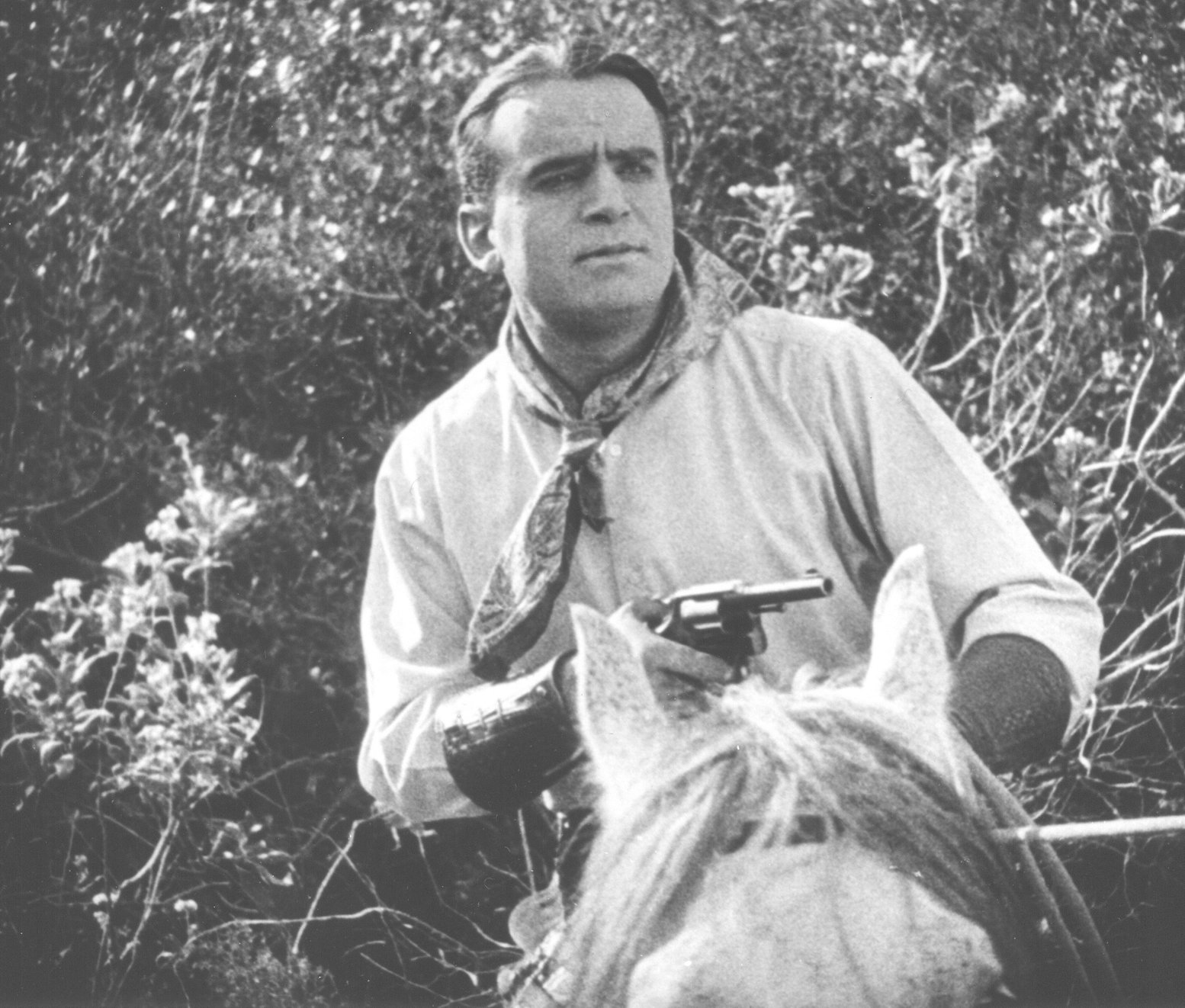

Wild and Woolly (1917)

Toronto Film Society presented Wild and Woolly (1917) on Monday, January 22, 1968 as part of the Season 20 Monday Evening Silent Film Series, Programme 3.

Programme No. 3

Monday January 22, 1968

8.15 pm

A DOUGLAS FAIRBANKS double bill:

(1) The Mystery of the Leaping Fish (1916)

Produced by the Triangle Film Corporation

Scenario by Anita Loos

Directed by John Emerson

Players: Douglas Fairbanks, Alma Rubens, Bessie Love

Released: August (?) 1916

A spoof on detective stories (not mentioning Sherlock Holmes by name).

INTERMISSION

(2) Wild and Woolly (1917)

Produced by the Douglas Fairbanks Pictures Corp.

Released by Artcraft Pictures Corporation

Story by Horace P. Carpenter

Scenario by Anita Loos

Directed by John Emerson

Copyright June 16, 1917, by Artcraft Pictures Corp.

(5 reels)

Cast:

Jeff Hillington………………Douglas Fairbanks

Nell Larrabee………………Eileen Percy

Butler……………………….Joseph Singleton

Banker………………………Forest Seabury

Pedro, the clerk……………Charles Stevens

Engineer……………………Tom Wilson

Indian Agent………………..Sam de Grasse

A spoof on Westerns. (Is there nothing new?)

(Estimated running time of the two films: 2 hours 10 minutes)

DOUGLAS FAIRBANKS (1883-1939)

The screen career of Douglas Fairbanks divides itself into three periods:

1: 1915-1920 Modern comedies (These are the films that brought him world-wide popularity).

2: 1920-1929 Costume pictures (These are the films by which he is best remembered).

3: 1929-1934 Talking pictures (These films, ranging in type from Shakespeare to travelogue, belong to the ebb-tide of his popularity and are generally forgotten today).

The two films on tonight’s program belong to Period 1; and so for a modern appraisal of the Doug Fairbanks of that period, we turn to a little book called THE SILENT VOICE (1966) by Arthur Lenning:

Douglas Fairbanks was an athletic, clean-cut man, but he wasn’t extraordinarily handsome nor was he even very young when his motion picture career began. Yet within a short time he achieved world-wide popularity. His stardom didn’t come as a result of press-agent ballyhoo; he was more genuine. Somehow he answered a need. He appealed to certain visions that Americans liked to have of themselves.

By the turn of the century the pioneer spirit was rapidly fading; the frontiers had been reached and life was becoming industrialized. The epic confrontation of man with the wilderness shrank to an encounter with the time clock. A solitary horse ride through a mountain pass gave way to a jouncing trip in a trolley car. Although the romance of life was waning, it was preserved, defined, and even encouraged by Teddy Roosevelt, the bookish, near-sighted Eastern Dude who transformed himself into a cowboy, hunter, and rough rider. Far back in the mythic unconsciousness of well-dressed, neatly combed, car-driving young men flickered the attraction for the rugged life. By 1915, when Fairbanks’ motion picture career actually began, the war fever raged throughout the land. It was not that America had taken sides completely (we did not of course enter the First World War until 1917), but that Europe was embroiled in the heroism and futility of chivalrous death while America was doing nothing but making money. Thus the bravery, nobility, courage, and adventure of the European war dried out for release domestically, and as men grew more guilty about their tame existence, the life of action beckoned even more alluringly. To a nation of Walter Mittys, Fairbanks answered the dream; he became, in a ssense, its alter ego.

His early films all follow the same pattern. AS they open, Doug is a mild and tame young man who does not consciously seek adventure, but when its challenge comes, he does not refuse its call. Indeed, he is much like the nation itself: peace loving, yet capable of war; seemingly soft, yet hard; naive, yet instinctively shrewd; shy, yet aggressive; and spoiled, yet essentially unspoiled. Doug was really a pioneer in disguise, his potential hidden not only from his acquaintances but also from himself. He does not realize his own abilities, the inherent gifts that the tame life has not tapped. But when the call to adventure comes, he has no difficulty transforming himself into a hero; indeed, he has only to shed his Clark Kent appearance to become the Superman. Years of apartment living (The Clouds Roll By, 1919), years of international smart set life (The Mollycoddle, 1920), and years of tame urban living (His Majesty the American, 1916), have not hampered his wind or weakened his muscles. He has only to need to jump or to run or to climb a rope and he does so, magnificently. This is part of the myth. Yet, somehow, the myth comes off.

Although Doug’s character is hardly a subtle one, it is difficult to define that rare quality of personality which raises his works to a realm where modern audiences, so jaded, cynical and bored, forget outmoded styles, gestures, and techniques and react favorably to Fairbanks. How, in such an antiheroic age as today, can Fairbanks still retain his appeal? Above all, he has charm, not the charm of a finishing school or of a Dale Carnegie course, but a direct, ingenuous, good-natured charm. The naivete and simplicity of his character do not seem trite but fresh and welcome. Doug frequently laughs at himself, at the camera crew, at the absurd conventions of the medium itself. He seems to be saying, “Well, you know, folks, this is ridiculous, but what the hell, it’s fun.” This sense of improvisation, this exaggeration and spoofing, makes us feel that Doug is sharing, not merely portraying humor and good will–those rare commodities which never date.

End of quotation. Actually, we can’t help wondering: if Fairbanks’ popularity in the United States was due to the psychological climate of the United States at that time, what accounted for his enormous popularity in Europe? (Just the same, THE SILENT VOICE is an excellent little book which we wish we had discovered sooner. We particularly recommend the chapters on Griffith, especially THE BIRTH OF A NATION).

* * *

When Adolph Zukor in 1912 launched a new motion picture company, Famous Players in Famous Plays, by releasing in North America the French-made Sarah Bernhardt film Queen Elizabeth, he set in motion a number of waves that have been a long time a-dying. The box-office success of this film did more than permit the fledgling company to survive (which it still does; and incidently so does old Zukor himself, at the age of 95); it helped to set off the “craze” for feature films which revolutionized the American film industry within the next two years (and still shows no signs of abating) . . and it broke the unwritten law that forbade self-respecting stage actors to appear in moving pictures–a rule that was frequently broken, of course, but only in cases of dire economic necessity. The law wasn’t repealed overnight, but the fact that the great Sarah Bernhardt, whose prestige was beyond dispute, and had consented to perform in this new medium, this mute bastard of stage and photography, set a revolutionary new precedent.

After the success of Queen Elizabeth, Zukor’s company went into production for itself, starting out by photographing the current classic of the American theatre: James O’Neill (father of Eugene) in The Count of Monte Cristo . . and rival movie companies were quick to climb on the bandwagon. Everybody began making features, and there was a scramble to sign up all the oustanding Broadway stars.

One of these outstanding Broadway stars was Douglas Fairbanks, who, early in 1915 (he was then 32 years old), was signed to a contract by D.W. Griffith’s company (which in July of that year united with the companies of Thomas Ince and Mack Sennett to form the Triangle Film Corporation). Taking a cue from The Birth of a Nation, which had had its New York opening earlier that year in a big legitimate theatre, Triangle acquired a new theatre on Broadway: the Knickerbocker, and had a gala opening in September 23, 1915, with a $2 top admission price. The program featured Douglas Fairbanks’ first film, The Lamb–not so much because Triangle had any illusion that The Lamb was another Birth of a Nation, but because it was the only film that was ready. But much to everyone’s surprise the picture proved a hit. The twenty-year screen career of Douglas Fairbanks had begun.

He was born in Denver, Colorado, on May 23, 1883; and at the age of 17 he went to New York in an attempt to crash Broadway, which, after five years of bit-parts and non-theatrical jobs, he finally did, achieving his first important role in 1905 in A CASE OF FRENZIED FINANCE. Three years later he officially became a star in ALL FOR A GIRL (1908). Fairbanks has been so long associated with films that one forgets that he was a popular star of the New York stage for seven years before he was lured to Hollywood (“temporarily”) by the irresistible offer of $2000 a week. (We shouldn’t leave you with the impression that it was Sarah Bernhardt’s example alone which broke down the stage stars’ prejudice against movies).

The Lamb (adapted from one of his stage successes, THE NEW HENRIETTA–which later became a screen vehicle for Buster Keaton) was directed by Christy Cabanne (whose Enoch Arden we’ve seen) under the supervision of D.W. Griffith. “Griffith” (says Terry Ramsaye in A MILLION AND ONE NIGHTS) “was not pleased with the new star’s athletic tendencies. Fairbanks seemed to have a notion that in a motion picture one had to keep eternally in motion, and he frequently jumped the fence or climbed a church at unexpected intervals not prescribed by the script. Griffith advised him to go into Keystone comedies”. This latter advice was not quite the contemptuous insult it has sometimes been made to sound; Mack Sennett was one of Griffith’s partners at that time, and Fairbanks with his athletic exuberance would undoubtedly have been a great asset to him. However, it was obvious that Griffith had no use for Fairbanks himself, so he turned the problem over to his production chief, who had the inspired hunch to team Fairbanks with a new director, John Emerson (a former stage star and playwright), and the young staff writer, Anita Loos. The latter incorporated Fairbanks’ off-stage personality into her scripts, and poured her irreverent sense of fun and satire (which years later again paid off in her novel GENTLEMEN PREFER BLONDES) into her plots and her ready wit into the subtitles, and the result was a series of comedies (eleven of them in as many months) which so pleased the public that by the end of 1916 Fairbanks’ salary had been increased to $10,000 a week.

Nevertheless Fairbanks left Triangle then and set up his own production company, bringing with him Emerson and Loos and most of the rest of his regular staff. During 1917 and 1918 his films were released by Artcraft which was controlled by Famous Players-Lasky; but in 1919 he and Mary Pickford, Chaplin and Griffith formed their own production-distribution company, United Artists, with which he remained for the rest of his life.

In 1920 he took two decisive steps: he married the screen’s most popular actress, Mary Pickford, to the great delight of their fans (though it shocked many that both had to divorce their current mates to make this possible),–and he tried a bold experiment: he departed from his modern comedies (as described above by Mr Lenning) to produce a costume melodrama, The Mark of Zorro. (Actually it was not basically a departure, for in spite of the period setting, Doug still played his standard Clark Kent-Superman role). This proved so extraordinarily successful that for the rest of the 1920’s he produced nothing but big costume spectaculars in which he played the swashbuckling heroes. In contrast to the old carefree days of one per moth, his films were not produced at the rate of about one a year–eight films in nine years, to be exact. (Compare with the 30 modern comedies in five and a half years).

With the coming of sound he abandoned his familiar Fairbanks role, and between 1929 and 1934 he made five films of various kinds, of which some were rather good, though only The Taming of the Shrew seems to reappear on Film Society screens. However, the public had lost interest. The good old days were gone. Fairbanks retired from film production and spent the rest of his days in restless activities until a coronary thrombosis ended the athlete’s life in December, 1939, at the age of 56.

* * *

So far as tonight’s program is concerned, the costume melodramas and the talkies are far in the future. Our two films come from the 1915-1920 period; and to let you know where they come from, we print herewith the titles of all thirty, with their approximate release dates:

Produced by Triangle Film Corporation:

1915

The Lamb (released Sept 23)

Double Trouble (November)

1916

His Picture in the Papers (Feb)

The Habit of Happiness (March)

The Good Bad Man (April)

Reggie Mixes In (June)

Flirting with Fate (June)

The Half-Breed (July)

The Mystery of the Leaping Fish (Aug)

Manhattan Madness (Sept)

American Aristocracy (Nov)

The Matrimaniac (Dec)

The Americano (released Jan 1917)

Produced by the Douglas Fairbanks Pictures Corporation:

(a) Released by Artcraft:

1917

In Again, Out Again (May)

Wild and Woolly (July)

Down to Earth (August)

The Man from Painted Post (Oct)

Reaching for the Moon (Nov)

A Modern Musketeer (released Jan 1918)

1918

Headin’ South (March)

Mr Fix-It (April)

Say, Young Fellow (June)

Bound in Morocco (Aug)

He Comes Up Smiling (Sept)

Arizona (Dec)

(b) Released by United Artists:

1919

A Knickerbocker Buckaroo (June)

His Majesty the American (Sept)

When the Clouds Roll By (released Jan 1920)

1920

The Mollycoddle (June) (Shown by TFS last season)

The Nut (released March 1921; it was made after The Mark of Zorro but before the latter’s release).

Anita Loos, in her entertaining autobiography A GIRL LIKE I (1966), gives the impression that His Picture in the Papers was Fairbanks’ first film; but Miss Loos’ memory is manifestly faulty throughout the whole book. Read it for general information about Hollywood at this period, but be very wary about believing it in detail. (Anyone who claims to have made herself very familiar with Intolerance, and yet doesn’t remember that the heroine of the Huguenot episode is not rescued in the nick of time, is obviously extremely unreliable. Like many another person, Miss Loos–no doubt quite unconsciously–bridges her lapses of memory with a vivid imagination instead of with research).

Since we have a little space left, we might as well throw in the rest of the Fairbanks filmography:

Group II: Costume pictures (silent)

The Mark of Zorro (Dec 1920)

The Three Musketeers (Sept 1921)

Robin Hood (Nov 1922)

The Thief of Bagdad (March 1924)

Don Q, Son of Zorro (June 1925)

The Black Pirate (March 1926)

The Gaucho (Nov 1927)

The Iron Mask (March 1929)

Group III: Talking pictures

The Taming of the Shrew (Dec 1929)

Reaching for the Moon (Jan 1931; and not to be confused with his 1917 film of the same title)

Around the World in 80 Minutes (Nov 1931)

Mr Robinson Crusoe (Sept 1932)

The Private Life of Don Juan (Nov 1934; made by Alexander Korda)

*+*+*+*+*+*+*+*+*+*+*+*+*+*+*+*+*+*+*+*+*+*+*+*+*+*+*+*+*+*+*+*+*+*+*+*+*+*+*+*+*+*+*+*+

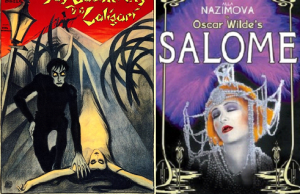

Next show: Monday February 19:

(1) Nazimova in Salome (1922) (NB: Abridged edition)

(2) The Cabinet of Doctor Caligari (1919)

Leave a Reply