Gabriel Over the White House (1933)

Toronto Film Society presented Gabriel Over the White House (1933) on Sunday, February 24, 2019 in a double bill with Blondie Johnson as part of the Season 71 Sunday Afternoon Special Screening #8.

Production Company: Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer. Director: Gregory La Cava. Screenplay: Carey Wilson, additional dialogue Bertram Bloch, based on the novel by T.F. Tweed. Producers: William Randolph Hearst, Walter Wanger. Cinematographer: Bert Glennon. Film Editor: Basil Wrangell. Music: William Axt. Art Director: Cedric Gibbons. Gowns: Adrian. Release Date: March 31, 1933.

Cast: Walter Huston (Hon. Judson Hammond, President of the United States), Karen Morley (Pendola Molloy), Franchot Tone (Harley Beekman, Secretary to the President), Arthur Byron (Jasper Brooks, Secretary of State), Dickie Moore (Jimmy Vetter), C. Henry Gordon (Nick Diamond), David Landau (John Bronson), Samuel S. Hinds (Dr. H.L. Eastman), William Pawley (Borell), Jean Parker (Alice Bronson), Claire Du Brey (Nurse), Oscar Apfel (German Delegate to Debt Conference), Mischa Auer (Mr. Thieson), Henry Kolker (Sen. Langham, Senate Majority Leader), Akim Tamiroff (Delegate to the Debt Conference).

The director of today’s film, Gregory La Cava, is probably best known for directing the 1936 version of My Man Godfrey. Gabriel Over the White House is an unusual film, although maybe not such a strange choice for this former cartoonist who originally worked for Hearst Corp. as the editor-in-chief for its International Comic Films division. Produced during the pre-Code and Depression era, it seems to have been based on two novels; T.F. Tweed’s Rinehard and the second being the same title as the film written by Anonymous. On January 30, 1933, it became world news that Hitler had been elected as the Reich’s chancellor of Germany. The Depression was at its height, and people were organizing everywhere to try and force their governments to help them survive. In the US, Democrat Roosevelt had just taken over the presidency from Republican Hoover and the idea that today’s film was a message from MGM and especially William Randolph Hearst appears to be evident from many of the writings with regard to what was politically going on in those times. Louis B. Mayer, a strong Republican, wouldn’t allow the film to be released until after Hoover had left the White House.

In the film, there is a protest march of the Army of the Unemployed and this would be a reference to the real-life protest march of the Bonus Army which took place in May 1932 when veterans of WWI marched on Congress to demand early payment of their military service bonuses. Although this was a peaceful protest, Hoover requested that General Douglas MacArthur lead an armed force of 400 infantry, 200 cavalry and 6 tanks, to attack and gas the veterans, burning their makeshift tent camps to the ground. Two marchers were killed, 55 injured and 135 arrested. Angry Bonus March veterans in Pennsylvania set out to recruit 1 million men into their Khaki Shirts movement, a US. Fascists organization founded in the summer of 1932.

There is complex history here, but it’s interesting background to be aware of when an early pivotal scene takes place. While the newly elected president is playing with his beloved nephew, played by the always adorable Dickie Moore, simultaneously a message by the leader of the Army of the Unemployed, John Bronson, is being broadcast on the radio. Is the president listening?

It’s certainly possible that this is to have been a message to or by the newly elected Roosevelt, if he had any private input with regard to the messages in the film. But was Communism and Fascism the answer to poverty, crime and world peace? It was already known, with Hitler in control of Germany, that a second European war was on its way. And Americans were much more aware of and frightened by Communism, so with Nazi organizations beginning to form throughout the States, fascism might have been less in the public’s eye. In the film, there’s a meeting that takes place with other world leaders to bring about world peace but it’s noticeable that there are no representatives from Africa. Perhaps it’s partially because the US didn’t lend them any money?

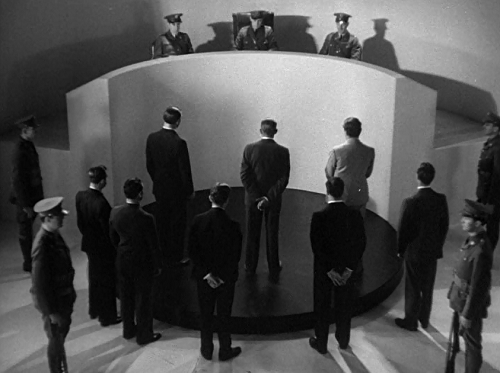

There are some rather shocking resolutions that this benevolent president turned dictator uses to handle criminals, allowing his right-hand-man to act as both judge and jury in a rather surrealistic courtroom. Watch C. Henry Gordon’s face—he plays crime boss Nick Diamond—in his last moments on the screen.

Franchot Tone and the not often seen Karen Morley play the President’s Secretary and Personal Secretary with intelligence, while Walter Huston is his usual outstanding self, and another Canadian-born actor to play an American president.

There will be a short just prior to the film, The Little King in Sultan Pepper. I have to admit that it’s a rather disturbing 7 minute short, but we’re assuming it was what was considered humorous and acceptable among the mainstream then while, when viewing it today, it projects what still goes on in places such as the Middle East and elsewhere.

Still, we hope you enjoy today’s film while it gives us something of interest to think about.

Introduction by Caren Feldman

Whatever one’s individual reaction to Gabriel Over the White House (and it is worth re-stressing that it is not an individual outcry, but one of a small but quite powerful group of near-Fascist films of the early 30’s, offshoots of the gangster cycle) the common-denominator reaction from almost all kids of audiences today is bound to be one of surprise. Surprise that such a film could have been made at all, surprise that it could have been made at that time, surprise most of all perhaps that it could come from MGM, a producer and star dominated studio, concerned far more with gloss and audience appeal than crusades. When they did pick up a subject that they could get their teeth into – e.g., prohibition and a film called The Wet Parade – MGM usually presented both sides of the picture so thoroughly that ultimately no viewpoint at all emerged. Gabriel Over the White House however has all the directness and certainty of purpose of a Warner Brothers social melodrama. Louis B. Mayer made no secret of his antagonism to Roosevelt and his administration, and there are signs of Mayer’s personal tamperings with the script here. Both the “party-man” President of the opening reel, and the “enlightened” President of the bulk of the film are given lines, situations and clues which suggest identification with some of the less laudatory Roosevelt traits; but basically of course no clearly defined identification is intended. The film is political melodrama in the framework of fantasy, startling in the proffered solutions (views held by many at that time) and startling too in the topicality, 40 years later, of many of its political and social problems. What a monumental (and psychologically fascinating) double-bill it would make with Capra’s Mr. Smith Goes to Washington in which the efficient corruption of the villains frankly seems vastly preferable to the amateur and directionless “do-gooding” of its bumbling hero!

The New School by William K. Everson, February 25, 1972

Nineteen thirty-two was the depth of the Depression, the nadir. By the middle of 1932, industry was operating at half of its 1929 capacity and wages were down a full 60 percent from their 1929 high. Even without knowing the particulars, one could tell from the movies released in early 1933 that something was very wrong. Parachute Jumper, released in January, may have been lighthearted and snappy, but between the frames, it was clearly the product of a heartsick, disoriented country. An explicit expression of the same turmoil can be found in another early 1933 film, this one about a party hack who becomes president, nearly dies in a car wreck, and then is reborn as a visionary leader In Gabriel Over the White House, President Hammond (Walter Huston) represented the era’s collective fantasy of the ideal president. The picture is a fascinating document from a brief but distinct juncture in American history, a time when problems seemed so insoluble that the prospect of a dictator was attractive.

The film was based on a futuristic political novel by a British author, Thomas Tweed, about a president who becomes possessed by the angel Gabriel and solves all the world’s problems, circa 1950. In bringing the book to the screen, the filmmakers—producer Walter Wanger, director Gregory La Cava, and screenwriter Carey Wilson—not only steam-lined the story but made it more immediately relevant by having it take place in the America of 1933. Daringly, Hammond, at the start, is not just presented as a mediocrity but as an identifiably Republican sort of mediocrity. He supports Prohibition and calls unemployment a “local problem.” After he is conked on the head, he becomes more than willing to used federal power.

The movie makes excellent use of Huston’s range. As an actor, he tended to look powerful and resolute when stern, and vapid or demented when smiling. Accordingly, in the beginning of the movie, he smiles a lot. Later, in his great man incarnation, he is serious and talks in a brisk monotone, as though channeling a force speaking through him. It’s strange, all these decades later, how Huston’s portrayal of President Hammond still taps into an American viewer’s yearning for a strong and benevolent leader. Advised to call out the military when the Army of the Unemployed is about to march on Washington—yet another pre-Code reference to the Bonus Army—Hammond says, “I refuse to call out the Army on the people of the United States.”

Instead, he meets the marchers and congratulates them for arousing “the stupid, lazy people of the United States to force their government to do something before everybody slowly starves to death.” He enlists the men in an “army of construction,” sets aside billions to stimulate purchases, to shore up banks, and to protect homeowners against foreclosures. He also solves the gangster problem (with tanks) the Prohibition problem (through repeal), and the problem of the world peace (by scaring European leaders with American air power). He is able to get so much done because he dismisses Congress, fires his cabinet, and threatens to declare martial law. In the same year that Germany elevated Hitler, Gabriel Over the White House made an alarmingly seductive case for an American dictator.

Before the picture was released, forces within the film industry were worried that it might be too incendiary to unleash on an angry public. MGM mogul Louis B. Mayer, an active Republican, was appalled to realize his studio had made a film that was an unmistakable repudiation of the Hoover administration. James Wingate of the Studio Relations Committee was afraid it might “foment violence against the better elements of established government” and cause protestors to descent on Washington en masse. In February 1933, Will Hays—fearful of government intervention in the film industry—expressed concern about two bills introduced in the New York legislature to prevent the certification of any motion picture that would “tend to undermine public confidence in public officials and their conduct of office.”

Clearly, Gabriel Over the White House was primed to be a national sensation, but then Mayer did one thing that changed everything. He held up the film’s release until after Franklin Roosevelt’s inauguration. Released twenty-seven days into the new president’s term, the film was no longer a comment on the current president’s inadequacies, but a political fantasy that was old news on arrival. Audiences saw President Hammond asking for special powers to combat the Depression, something that Roosevelt—a fan of the film, as it turned out—had already done weeks before. The move was greeted with critical success but popular indifference.

Dangerous Men by Mick LaSalle (2002)

Notes Compiled by Caren Feldman

Leave a Reply