Leaves From Satan’s Book (1921)

Toronto Film Society presented Leaves From Satan’s Book (1921) on Monday, November 4, 1957 as part of the Season 10 Monday Evening Silent Film Series, Programme 2.

The programme will open with a Laurel and Hardy comedy, Double Whoopee. This two-reeler has considerable of their traditional type of follery, but is perhaps of special interest to a film-society audience as it contains broad satire on Erich von Stroheim (and–could it be?–on Emil Janning’s hotel doorman in The Last Laugh); also it is graced by one of the earlier appearances of Miss Jean Harlow.

THE SCANDINAVIAN FILM – II

Leaves From Satan’s Book (Denmark 1921). Directed by Carl Dreyer. Produced by Nordisk Films Kompagni. Script: Edgar Hoywer, from a novel by marie Corelli; re-written by Dreyer (under protest from Hoyer). Photography: George Schneevoigt. Decor: Dreyer, with technical assistance of Axel Bruun and Jens G. Lind. Cast includes Helge Nissen as Satan; Halvard Hoff as Jesus; Clara Pontoppidan as the Stationmaster’s Wife.

Carl-Theodor Dreyer, the most noted of Danish directors, is also one of the world’s most unique and individual film-makers. Specializing in austere studies of human suffering and religious experience, and refusing to make a film in which he does not believe, he has found financial backing, public and sometimes even critical support not always easy to come by. As a result his works in recent years have been very few though notable. His most famous film, The Passion of Joan of Arc, ranks as one of the genuinely great cinema classics. The reputation of his stark portrait of medieval witch-hunting, Day of Wrath, was slow to build but is now secure. Between these two stands his strange and subtle horror-film Vampyr. His latest picture, Ordet (The Word), dealing with religious differences in an isolated community and a modern miracle, strongly impressed visitors to last summer’s Stratford (Ontario) Film Festival. Dreyer hopes (as does France’s Abel Gance) to film a life of Christ.

The film we are to see tonight is, of course, not as mature and powerful a work as his later masterpieces, but is of decided interest as an example of his earlier work, in which can be seen the beginnings of his individual style and his characteristic use of lighting and decor. Some critical comments follow:

“Dreyer’s early work, such as Leaves From Satan’s Book and Master of the House (1925) revealed an intelligent film mind and an interest in human detail” – Richard Griffith in The Film Since Then.

“This honest man and conscientious artist began by imitating the Americans. Griffith’s Intolerance had greatly impressed him” – Bardeche and Brasillach in History of the Film.

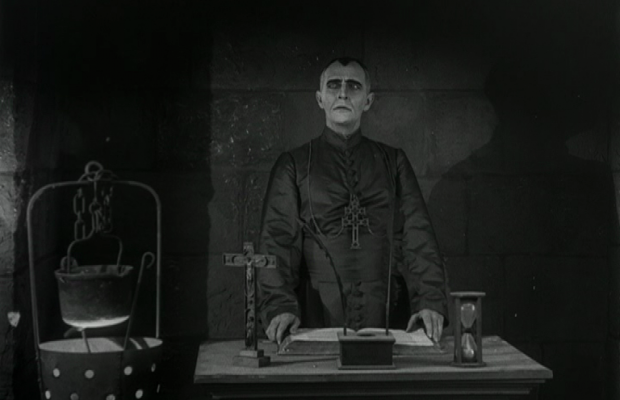

“His second film, Leaves From Satan’s Book, was clearly influenced by Grifith’s Intolerance, but already his work showed the hand of a man who understood the film medium and who had highly original ideas about the use which might be made of it. In this film Satan appears in each of the four sections wearing a different ‘mask’, his purpose being to fulfil his mission of bringing suffering on humanity. In the selection of this theme we see both the influence of Griffith and the preoccupation with the forces of good and evil which has been characteristic of all Dreyer’s films.” – Forsyth Hardy in Scandinavian Film.

“Dreyer occupies a unique place–in Danish cinema he is not only second to none but stands alone, bearing no resemblance to other Danish directors–but does not hold an isolated position in Cinema history. As early as 1920 he was the first Scandinavian director to introduce Griffith’s principles of editing, together with an expressive close-up technique also similar to that of Griffith” – Boerge Trolle in Sight & Sound.

Ebbe Neergaard, in the British Film Institute’s Index on Dreyer, writes:

“One evening in 1918, all Nordisk Film directors were invited to see D.W. Griffith’s Intolerance. After the show, Dreyer walked home through the quiet street and let the evening’s impressions sink in, wondering how the things he had seen could best be used in DAnish films. Nordisk films had from time to time treated great themes, but only in a naively moralizing, romantic style. Griffith moralized in a different way, attacking the unceasing wickedness of mankind through the ages. It was not only the magnitude of Griffith’s theme that attracted Dreyer but his combination of fantasy and realism. In Leaves From Satan’s Book Dreyer shows how the devil leads man to betray his neighbor and how he disguises himself–in different ways through the ages. The film suffers from obvious weaknesses in the script, which is rather too naive in places, and it is also oversimplified in construction, the four episodes frollowing each other with a certain monotony of action. It does not, as Griffith did, emphasize the human theme rather than the time theme. But it is unfair to compare a man working on his second film with one who has reached mastery through ten years’ experience. In comparison with his first film, this shows astonishing progress and is the only Danish film in which this type of allegorical theme has been treated with any success. Experimenting with new ideas for decor, some sequences have an expressive simplicity of effect not previously seen in those days of overcrowded interiors. He built complete large sets not for publicity but to provide the best conditions for the effects he wanted–as in the images of Marie Antoinette being led to her cell. In a great panning shot the camera follows her down the grand staircase into the cell at the right-hand corner of the frame. This panning and the depth of the images effectively reproduce the queen’s changing mood during her martyr’s walk.

“The method of editing was new in Denmark–inspired by Griffith cetainly–but primarily by the material. In the Finnish episode, there are close on 500 cuts, each shot averaging about 3 1/2 seconds. The companyexecutives were horrified when they heard how Dreyer was “ruining” the film. Before they let him direct the other three episodes they made him complete the cutting of the Finnish part and show it to the directors. As it turned out, the rhythm was so right for the tense action that the short cuts appeared perfectly natural. Dreyer was allowed to go on with the film. Others too were dissatisfied with the quick shots: the actors. It did not give them a chance to “act out”, as they said. Clara Pontoppidan did not like the big close-ups either, which Dreyer, under Griffith’s influence, had introduced to heighten the emotional action; she wanted someone to ‘act at‘. But Dryer knew precisely how he wanted the film to be acted. When a player had learned to understand the big close-up completely, both what dangers it holds and what possibilities for expression, then he or she would be able to give of their best. Clara Pontoppidan did it, and when she saw the result of their work together she threw her arms round Dreyer’s neck. Her death scene is a moving piece of acting. The most important Danish film critic of the time wrote: ‘Foremost perhaps stood Clara Pontoppidan, who in a close-up cried out in dumb anguish all her suffering and pain, as the cold steel of a knife slid into her heart. It was done so beautifully that one instantly loved her for it.'”

This technique was developed to its ultimate, of course, in Dreyer’s direction of the French actress Falconetti in The Passion of Joan of Arc, a performance that was almost entirely made up of large and deeply moving close-ups. Since then, however, he has not used the close-up to so great a degree, and he has forsaken fast cutting for a very deliberate pace.

Leave a Reply