Metropolitan (1935)

By Toronto Film Society on December 8, 2019

Toronto Film Society presented Metropolitan (1935) on Sunday, December 8, 2019 in a double bill with They Shall Have Music as part of the Season 72 Sunday Afternoon Film Buffs Series, Programme 3.

Production Company: Twentieth Century-Fox. Producer: Darryl F. Zanuck. Director: Richard Boleslawski. Screenplay: Bess Meredyth, based on her story, and George Marion Jr. Cinematography: Rudolph Maté. Editor: Barbara McLean. Art Direction: Richard Day. Costumes: Arthur M. Levy. Release Date: November 8, 1935.

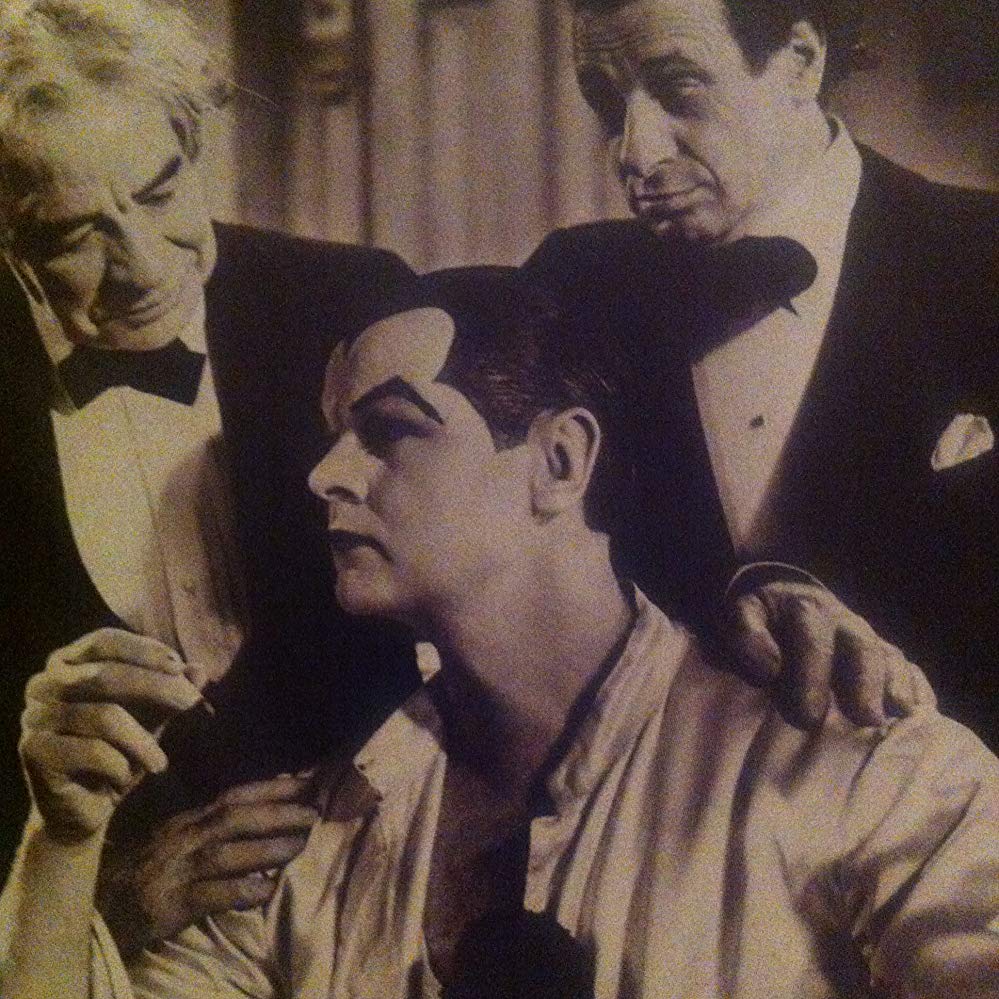

Cast: Lawrence Tibbett (Thomas Renwick), Virginia Bruce (Anne Merrill), Alice Brady (Ghita Galin), Cesar Romero (Niki Baroni), Thurston Hall (T. Simon Hunter), Luis Alberni (Ugo Pizzi), George Marion Sr. (Perontelli), Adrian Rosley (Mr. Tolentino), Christian Rub (Weidel), Franklyn Ardell (Marco), Etienne Girardot (Nello), Jessie Ralph (Charwoman), Lynn Bari (Chorus Girl), Madge Bellamy (Woman in Negligée), Walter Brennan (Grandpa), Jane Darwell (Grandma).

Lawrence Tibbett Returns to the Screen in the New Musical Film, Metropolitan, at the Music Hall.

Among the varied splendors of the Lawrence Tibbett film at the Radio City Music Hall, perhaps the special triumph is its conclusive demonstration that it is possible for a musical picture to end too soon. After the operatic sequence in which Mr. Tibbett sings the prologue from “I Pagliacci”, the experienced filmgoer anticipates, not without misgivings, that the star will next inflate his baritone to the needs of the hackneyed “vesta la giuba” aria. At this point, Metropolitan artfully comes to a close, while the applause for Mr. Tibbett’s magnificent rendition of the prologue is still filling the auditorium. Metropolitan is a happy début for Darryl F. Zanuck as a producer for the new Twentieth Century-Fox organization. Superbly stirring in its choice and execution of the musical numbers, it is also a gay and spirited satire on the social exclusiveness of opera management. The film is quite as successful in celebrating Mr. Tibbett’s return to the screen as One Night of Love was for Grace Moore, his associate in the musical photoplays of five or six years ago. Not only does the distinguished baritone endow the cinema with an important musical talent, but he also brings to it a vigorous personality and an engaging acting gift. In the recent operatic films, the screen, carefully feeling its way in a tentative effort to blend opera and screen narrative, has insisted on clipping the arias so as to escape the peril of visual monotony. Metropolitan gallantly suppresses this shibboleth and allows Mr. Tibbett to hold the screen for fairly lengthy intervals, thereby permitting us to savor the full emotional richness of the music. The selections range all the way from “The Barber of Seville”, “Carmen”, and “I Pagliacci” to “The Road to Mandalay” and the enchanting Negro spiritual “Glory Road”, which Mr. Tibbett performs with vast and delightful skill. The story, though possessing no more than a wisp of plot mechanics, is excellent in its own right. Aiming a savage blow at the Metropolitan Opera Association for its treatment of American singers, the authors present Mr. Tibbett as a gifted baritone who is shackled to minor roles in the mob scenes because the directors will not give him his chance. Thereupon an eccentric coloratura (who seems to be modeled after one of our front-page divas) decides to form a rival company in Philadelphia, and she assembles Mr. Tibbett and other musicians whom the Metropolitan has ignored. Her excesses of temperament, however, prove too much, and when she finally walks out on the company, the enterprise seems about to founder for lack of money. In its discussions of the troupe’s financial problems, Metropolitan becomes an ironic commentary on the barriers which opera as an art form erects both against those who would serve the muse and against a vast potential audience. Alice Brady gives a gloriously demented performance as the temperamental diva. Virginia Bruce, whose timing in The Great Barnum was so perfect that spectators refused to believe someone was singing for her, is equally effective this time as an ambitious soprano. Cesar Romero plays a debonair tenor skillfully and Luis Alberni is again hilarious as a passionately Latin music-lover. There are additional performances of excellence by George Marion Sr, Etienne Girardot, Jessie Ralph, and Thurston Hall. Metropolitan is very likely the best musical film of the season.

The New York Times by Andre Sennwald, October 18, 1935

Notes compiled by Caren Feldman

SPOT THE CANADIAN

Metropolitan art director Richard Day, born on May 9, 1896 in Victoria, BC, was one of Hollywood’s most sought-after designers. Before starting his career, he served with the Canadian Army during WWI, attaining the rank of captain. While stationed in London in 1918, he met and married a nurse’s aide; after the war’s end the couple returned to Canada, where Day tried to make a go of it as a commercial artist. In 1920, his father bankrolled a trip down to Hollywood in the hopes that Day could find more work there. For the longest time he couldn’t—until a chance meeting in a hotel lobby with director Erich von Stroheim led to his being offered a job on Foolish Wives (1922). From that point on, Day worked as Art Director on all of von Stroheim’s films, except for his sole sound film, Walking Down Broadway (eventually released in 1933 as Hello, Sister!). Day followed von Stroheim to Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer and worked steadily there throughout the 1920s. At the end of that decade, he joined Goldwyn/United Artists as Sam Goldwyn’s principal art director, working with him throughout most of the 1930s. By that time, he was so well regarded by his peers that he began receiving Academy Award nominations, beginning in 1931 for the features Whoopee! and Arrowsmith. He later moved on to Twentieth Century-Fox, where he was Supervising Art Director working personally on select films. During World War II, Day independently developed camouflage designs and relief mapping techniques. This led him to being inducted into the US Marine Corps as a major in 1942, a fact that obliged him to relinquish his Canadian citizenship. As befits a person who was integral to the look of some of the world’s most acclaimed classic movies (not to mention 1967’s camp classic Valley of the Dolls), Day became Hollywood’s most honoured art director. His filmography lists a staggering total of 265 movies made between 1922 and 1970. He received seven Oscars, starting with The Dark Angel (1935), followed by Dodsworth (1936), How Green Was My Valley (1941), My Gal Sal (1942), This Above All (1942), A Streetcar Named Desire (1951), and On the Waterfront (1954). He was also nominated 13 times for such blockbusters as Dead End (1937), Blood and Sand (1941), Joan of Arc (1948), and The Greatest Story Ever Told (1965), among many others. His final nomination was for Tora! Tora! Tora! (1970), his last major motion picture before his death in 1972.

Written by Leslie C. Smith

You may also like...

-

News

Frances Blau

Toronto Film Society | February 27, 2024On Monday, February 26th, 2024, Toronto Film Society lost longtime friend, supporter, and board member Frances Blau. Known for her sense of humour, her love of film, her generosity,...

-

Special Events

Monday Evening Film Noir Double Bill at the Paradise Theatre

Toronto Film Society | July 8, 2024The Toronto Film Society presents a film-noir double feature at one low price! The Window (1949) in a double bill with Black Angel (1946) at the Paradise Theatre on Monday, August...

Programming

Virtual Saturday Night at the Movies

Toronto Film Society | July 20, 2024Toronto Film Society is back in the theatre! However, we’re still pleased to continue to bring you films straight to your home! Beginning Season 73 until now we have...

4-

Toronto Film Society | July 8, 2024

Toronto Film Society | July 8, 2024

Monday Evening Film Noir Double Bill at the Paradise Theatre

-

Toronto Film Society | November 6, 2022

Toronto Film Society | November 6, 2022

-

Toronto Film Society | August 1, 2023

Toronto Film Society | August 1, 2023

Donate to Toronto Film Society – We’re now a Registered Charity!

-

Copyright © 2017 Toronto Film Society.

Leave a Reply