The Treasure of the Sierra Madre (1948)

By Toronto Film Society on November 6, 2022

Toronto Film Society presented The Treasure of the Sierra Madre (1948) on Sunday, November 6, 2022 as part of the Season 75 Sunday Afternoon Film Buffs Series, Programme 2.

Production Company: Warner Bros. and First National. Producer: Henry Blank. Distributor: Warner Bros. Director: John Huston. Screenplay: John Huston, based on the novel by B. Traven. Music: Max Steiner. Cinematography: Ted D. McCort. Film Editor: Owen Marks. Release date: January 14, 1948.

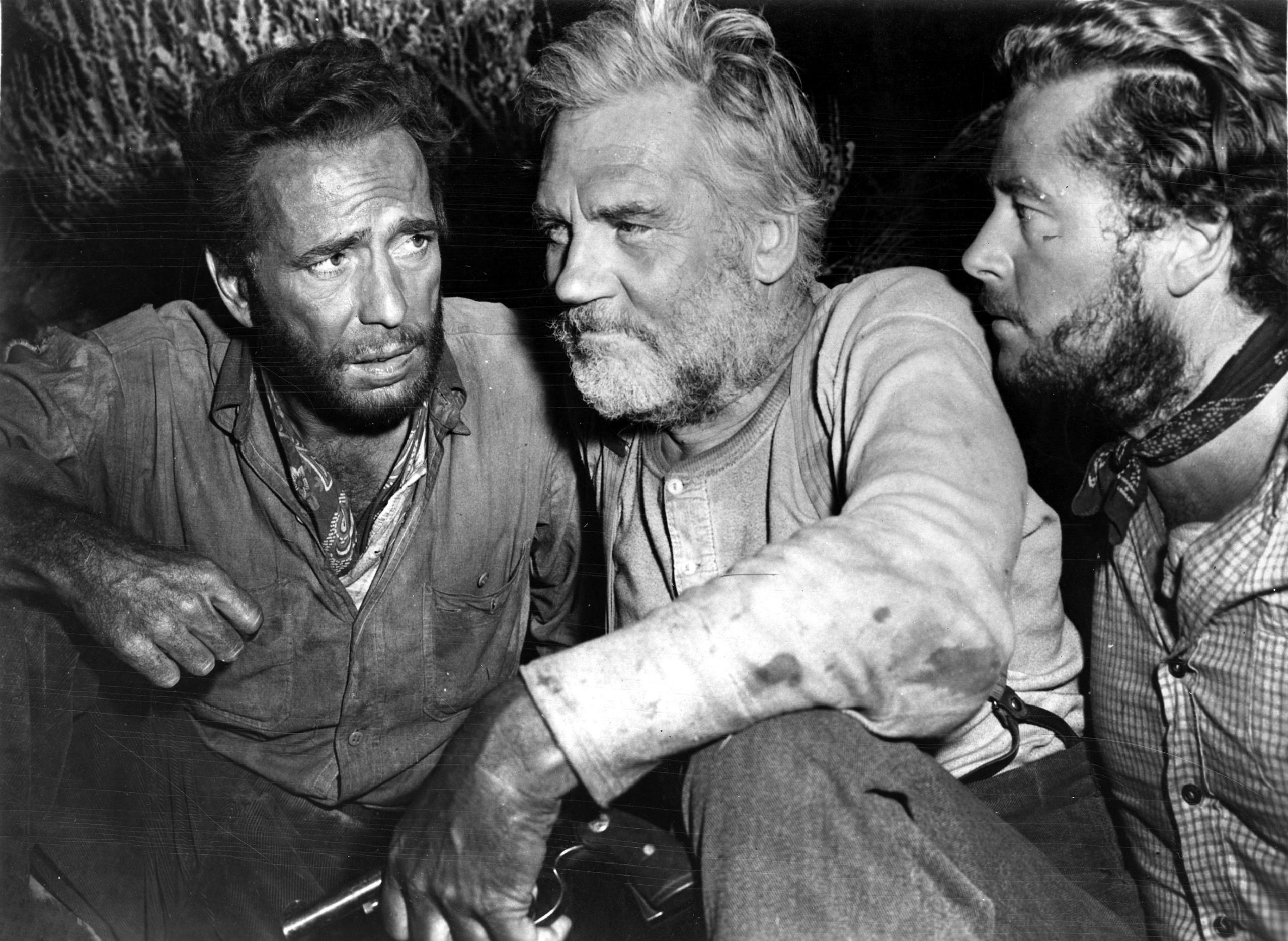

Cast: Humphrey Bogart (Fred C. Dobbs), Walter Huston (Howard), Tim Holt (Curtain), Bruce Bennett (Cody), Barton MacLane (Pat McCormick), Robert Blake (Mexican Boy Selling Lottery Tickets), Jack Holt (Flophouse Bum), John Huston (American in Tampico in White Suit).

Director John Huston’s The Treasure of the Sierra Madre stands to this day as arguably his greatest masterpiece – a tough, grittily brilliant morality tale about the power of greed and its effect on the human soul.

In a directorial career spanning over four decades that includes undisputed classics – The Maltese Falcon (1941), Key Largo (1948), and of course The African Queen (1951), and The Asphalt Jungle (1956), that’s no faint praise.

Based on a 1927 novel by reclusive pseudonymous author B. Traven, it’s a relatively simple tale about a couple of down-on-their-luck American drifters (Humphrey Bogart and Tim Holt) who team up with an old prospector (Walter Huston, the director’s father), to help them mine for gold in the Mexican Sierra Madre Mountains. Things take a dangerous turn when Bogart’s character develops an insatiable lust for gold and becomes increasingly paranoid and unhinged.

Huston, thanks in large part to his hard-edge script, a tough-as nails, no-nonsense filmmaking style and a cast that includes career-best performances by Walter Huston and Humphrey Bogart, works the material brilliantly to become one of the greatest films of all time.

The story behind the making of The Treasure of the Sierra Madre begins in 1935, when Huston was introduced to Traven’s 1927 novel. Huston greatly admired the material, and immediately thought about making a film of it. In 1941, Huston, after a successful screenwriting career, hit gold (so to speak) with his directorial debut The Maltese Falcon, a critical and commercial success which gave him the clout to choose his next projects, of which The Treasure of the Sierra Madre was at the top of the list.

Unfortunately, World War 2 sidetracked his plans for the film and it wasn’t until after the war ended that Huston and Warner Bros. began gearing up for the production in earnest, including the all-important casting.

The wartime years had been very kind to Humphrey Bogart, whose star rose considerably thanks to successes including Casablanca (1942), Sahara (1943) and To Have and Have Not (1944). In 1947, armed with a new contract which provided him with considerable clout, Bogart was eager to work with Huston again after The Maltese Falcon.

Indeed there is a famous story where Bogart, after being cast as Fred C. Dobbs in TOTSM, was quoted by a New York Post film critic outside a nightclub “Wait till you see me in my next picture, I play the worst shit you ever saw.” How true he was, as Bogart plays the part wonderfully against type. From the moment his character is introduced, we sense a charming yet slightly menacing edginess, a trait that will be intensely magnified during the ensuing gold expedition. It’s a brilliant performance and one of Bogart’s best. While Huston won the Best Supporting Actor Oscar, Bogart’s was criminally overlooked and remains one of the most glaring oversights in Oscar history.

By the time TOTSM was in pre-production, Walter Huston had become a renowned stage and screen actor, appearing in both leading man and supporting roles. Having made an uncredited appearance in The Maltese Falcon, he jumped at the chance to work with his son again and had complete faith in his vision, so much so that he even took his son’s advice and for the first time in his career, removed his dentures for a role.

This was a smart touch that accentuated his weathered, grizzled, yet wise personality, the sage of the trio, if you will. Referred to in the film only as Howard (it’s never clear if this is his first or last name), Huston brings the character of the scruff mountain man to vibrant life and created what would become the archetypal gold prospector. He’s a character who has seen it all, thinks of all the possible outcomes of a situation and usually knows how things will turn out before others do.

Amusing anecdote: fans of comedian Billy Crystal may recall a scene in the film City Slickers: The Legend of Curly’s Gold (1994) who upon discovering treasure, performs the “Walter Huston dance” (a true compliment if there ever was one).

The principal cast was rounded out by Tim Holt as Bob Curtain, portrayed as the closest to what could be called the everyman role, the character with whom audiences identify with the most. Holt was an interesting actor whose career alternated between B-movies (mainly westerns) and the occasional supporting role in more prominent productions including Stagecoach (1939) and Orson Welles’ The Magnificent Ambersons (1942).

On his own, Holt was a serviceable actor, but modern viewings of TOTSM put his performance at a disadvantage next to the likes of his prominent co-stars. His somewhat wooden, monotone delivery is considerably at odds with Bogart’s intense, almost feverishly method performance and Huston’s wonderfully nuanced characterization. His performance doesn’t diminish the film’s power, however, which remains a classic in spite of, and not because of him.

From the outset, it was clear that the film was going to go against archetypes of typical big budget Hollywood productions of the time. Typically, movies set in foreign locations either used rear projected backdrops or stock footage for establishing shots, as the American studio system frowned upon location shooting on location in foreign countries. But for authenticity, Huston insisted on shooting much of the production around San José de Purua, around 100 miles north of Mexico City. This was much to the chagrin of Warner Bros. executives, but it was a gutsy move typical of Huston’s maverick image, and one which arguably influenced a generation of directors to challenge filmmaking conventions.

Also, take notice that there’s nary a leading lady, or significant female character, to be found anywhere in the narrative. An especially unusual move especially in this classic age of film noir femme fatales, of romantic musicals and farcical comedies, where the likes of Judy Garland, Veronica Lake, and Lana Turner lit up the box office, and when a female role was considered all but obligatory to sell tickets. Again, credit must go to John Huston for eschewing contemporary Hollywood conventions and keeping the focus on the male leads, staying true to Traven’s source novel and the overarching theme of male bonding.

Studio head Jack L. Warner greenlit the initial proposed ten-week location shoot without having read the script. This was perhaps a sign of trust in Huston or more likely, that Huston was armed with the knowledge that the practice of executives not reading scripts beforehand, was a typical affair at Warner.

But with the location shooting going over schedule and over budget, Jack L. Warner ordered the production back to Hollywood. By that time, however, Huston had gotten the majority of footage he wanted, albeit at the cost of being the most expensive Warner Bros. production up to that time at a cost of $3 million. A grueling shoot by any standard, Huston never made it easy on his cast and crew. “If we could get to a location site without fording a couple of streams and walk through snake-infested areas in the scorching sun, then it wasn’t quite right,” recalled Bogart.

That quote is quite emblematic of the film’s enduring appeal, as Huston also invites the audience along on an unforgettable journey into a most inhospitable environment that shines a light on the darkest corners of men’s souls.

Almost 80 years later, the power of The Treasure of the Sierra Madre remains undiminished, and a powerful meditation on the nature of good and evil within all of us.

Notes by Michael Powell

You may also like...

-

News

Frances Blau

Toronto Film Society | February 27, 2024On Monday, February 26th, 2024, Toronto Film Society lost longtime friend, supporter, and board member Frances Blau. Known for her sense of humour, her love of film, her generosity,...

-

Special Events

Monday Evening Film Noir Double Bill at the Paradise Theatre

Toronto Film Society | July 8, 2024The Toronto Film Society presents a film-noir double feature at one low price! The Window (1949) in a double bill with Black Angel (1946) at the Paradise Theatre on Monday, August...

Programming

Virtual Saturday Night at the Movies

Toronto Film Society | July 20, 2024Toronto Film Society is back in the theatre! However, we’re still pleased to continue to bring you films straight to your home! Beginning Season 73 until now we have...

4-

Toronto Film Society | July 8, 2024

Toronto Film Society | July 8, 2024

Monday Evening Film Noir Double Bill at the Paradise Theatre

-

Toronto Film Society | November 6, 2022

Toronto Film Society | November 6, 2022

-

Toronto Film Society | August 1, 2023

Toronto Film Society | August 1, 2023

Donate to Toronto Film Society – We’re now a Registered Charity!

-

Copyright © 2017 Toronto Film Society.

Leave a Reply