The Thief of Bagdad (1924)

Toronto Film Society presented The Thief of Bagdad (1924) on Monday, January 13, 1964 as part of the Season 16 Monday Evening Silent Film Series, Programme 3.

Programme No. 3

(Monday, November 13, 1964)

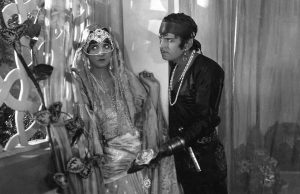

DOUGLAS FAIRBANKS in The Thief of Bagdad (1924)

(Approximately 120 minutes. There will be an Intermission at half time)

* * * * *

The Thief of Bagdad

Produced by Fairbanks-United Artists

Directed by Raoul Walsh

Story by Elton Thomas (pseudonym for Douglas Fairbanks and Kenneth Davenport)

Scenario by Lotta Woods

Settings by William Cameron Menzies

Photography by Arthur Edeson

Copyright: March 23, 1924

Cast

The Princess

The Thief’s Evil Associate

The Caliph

The Mongol Slave

The Slave of the Lute

The Slave of the Sand Board

The Holy Man

The Court Magician

The Mongol Prince

The Persian Prince

His Awakener

Julanne Johnston

Snitz Edwards

Brandon Hurst

Anna May Wong

Winter Blossom

Etta Lee

Charles Belcher

Sadakichi Hartman

So-jin

M. Comant

Charles Stevens

The following pertinent extract from Chapter 16 of Douglas Fairbanks: The Fourth Musketeer, by Ralph Hancock and Letitia Fairbanks, may be of interest:

Douglas planned to follow Robin Hood with a pirate story and the search, scenario, set and costume designs, and production plans were complete and ready to begin shooting when he popped into a staff meeting one day and exclaimed, “Let’s do an Arabian Nights story instead”….

For several weeks after the switch the place fairly hummed–with Arabian undertones–and when several tons of collateral reading had been consumed, digested, and summarized, Doug began looking for a gimmick on which to hang the story. Since he did none of the reading and only glanced at the summaries, one wonders how he managed to absorb enough “atmosphere” to make any decision, but Doug could surround himself with ten experts on the same subject and absorb, seemingly by mental telepathy, enough knowledge to make him sound like an authority.

He found his theme in a quatrain from Sir Richard Francis Burton’s translations:

Seek not they happiness to steal

‘Tis work alone will bring thee weal

Who seeketh bliss without toil or strife

The impossible seeketh and wasteth life.Which he condensed to “happiness must be earned”. On this bare dictum he built the story that took eight months to photograph and fifteen reels to tell. When the scenario was worked out to the last detail, it looked like a formidable undertaking. “If we don’t find some way to defeat that thing,” said Doug, pointing to the enormous manuscript, “it will defeat us by its sheer magnitude.”

The production staff finally had to make blueprint charts on which each set and sequence was listed and with these mounted on the walls of the offices, they were able to visualize the whole production and its day-to-day progress.

The finished picture was a symphony in fantasy, its texture woven of the slender thread of dreams. Its people moved in a fairyland where everything rested upon the light and airy foundation of fancy. This was the spirit of The Thief of Bagdad, and to translate it into a motion picture was a thing that conscripted all the artistic, mechanical, and imaginative talents of many people and into it went the heart and ambition of scores of artists.

First of all, there was the baic fact that when a thing is photographed, it is given substance and reality. This was purposely overcome by gleaming highlights along the base lines, destroying the reality of solid foundations. The magnificent structures, with their shadows growing darker as they ascended, seemed to have the fantastic quality of hanging from the clouds rather than being firmly set upon the earth.

To further the illusion, the environment of the characters was designed out of proportion to human fact. Flowers, vases, stairs, windows, and decorative effects were given a bizarre quality suggestive of the unreal.

William Cameron Menzies designed the sets and on paper they had the quality of fairyland Douglas was looking for, but when built they proved too solid and substantial-looking. After seeing several test shots Doug said, “Those things are anchored to earth. There’s nothing ephermeral about them and we’ve got to find a way to lift them up.”

Inconceivable as it might seem, four acres of cement was the answer. This, covered with several coats of black paint and polished to a high gloss, constituted the central plaza around which was constructed the city of Bagdad–walls, minarets, domes, stairways, bazaars and all. The end effect, with all this gaudy architecture reflected in the polished cement, was a city not quite of the earth nor yet of heaven but some sort of dreamland in between.

Raoul Walsh was the director and he recruited most of his mob extras from the local dives. He got plenty of color and contrast that way, but he also had his troubles handling them. He broke up more than one fight with his own fists. Another hazard he had less success with was that he was extremely attractive to women and whenever Doug wanted to find his director he looked over the lot and picked out the largest group of feminine fans. In its centre would be Walsh.

It could be said of The Thief of Bagdad what Pierre Berton once said in admiration of Disneyland: that somebody had obviously declared, “I don’t care how much it costs, but let’s do the thing properly!” No expense was spared to make the film an embodiment of all that we imagine whenever we read the Arabian Nights tales (especially from a lavishly illustrated edition). The unprecedented two million dollars that it cost (in those days before inflation) were channeled toward “doing the thing properly”, not into displaying a two-million-dollar “epic” in which “every dollar shows”. Viewing it today, one’s only possible regret is that it was made before the introduction of colour photography.

But in spite of the high praise from all the critics, and of the enthusiasm of small boys everywhere (especially this one), The Thief of Bagdad was considerably less popular at the box-office than his previous opus, Robin Hood, which had cost only $700,000. (Indeed, no other picture Doug ever made, before or afterwards, surpassed Robin Hood in popularity). Possibly the adult American population, in those feverish, cynical 1920’s, was little attracted to fantasy (it seldom is at any time). Possibly, too, the vogue for Orientalism, which had been so strongly influential in the years just before and during the War (Omar Khayyam…Scheherezade…Chu Chin Chow…and reflected,as late as 1922, in Doña Sol’s apartments in Blood and Sand), had already begun to wane. At any rate, Fairbanks took the hint and never again produced anything so extravagantly elaborate. But we doubt if he ever regretted it.

Incidentally, the Bagdad domes and minarets built for the film remained standing on the Fairbanks lot for many years afterwards, visible for miles around.

P.S. We’ll letyou in on another secret: the M. Comant” who played the Persian Prince was actually a woman.

* * *

Douglas Fairbanks is so identified with films that it is generally forgotten that he was a popular Broadway star for nearly ten years before he entered pictures in 1915. (Indeed, my parents, who saw him in Toronto in The New Henrietta in 1913, always considered him a much better actor on the stage than he ever became in films). Unlike some of the film stars we have been discussing, he wasn’t forced into films by an embarrassing absence of stage offers; he was lured into the despised medium by the astonishing and irresistable offer of $2,000 a week. He didn’t work his way up in films; he started off at the top as a star in his very first picture.

Fairbanks was not the only stage star brought to Hollywood in those days. In the period following the success of Sarah Bernhardt in Queen Elizabeth, the film companies were scrambling after the big names legitimate actors, such as Sir Herbert Beerbohm-Tree, De Wolfe Hopper, Lillian Russell, Forbes Robertson, James O’Neill (Eugene’s father), Webber & Fields, W.C. Fields, Anna Pavlova, Ethel Barrymore, John Barrymore, Gaby Deslys, Nance O’Neill, and a host of other names eminent at the time if not today. Most of them flopped. Their names meant not a damn at the box-office of Podunk Centre; and most of them could not adapt their acting styles to the silent film medium. There were, of course, many exceptions, such as Marguerite Clarke, Pauline Frederick, Alla Nazimova, and surprising as it might seem, the opera star, Geraldine Farrar. But the most exceptional exception was Douglas Fairbanks.

He was born in Denver, Colorado, on May 23, 1883. For a man whose smile was one of his greatest assets as a film personality, it is surprising to learn that he was a solemn child who never laughed or smiled until he was three years old. For a man who was celebrated for his athletics, however, it is not surprising to learn that even before that age he nearly drove his mother frantic by his constantly climbing trees, ladders, barn roofs, and anything he could. It was an inevitable fall from a roof that, astonishingly, elicited his first outburst of laughter. After that (and possibly because so much fuss was made over it) he soon learned that he could make more friends and influence more people by turning a smiling countenance to the world. For most of the rest of his life, up until his last sad years, he had a reputation as a cheerful, high-spirited, grinning, extroverted prankster and a born show-off. Nobody is all of one piece, of course, and side by side with this was the serious Fairbanks who was an astute businessman and the real brains behind most of the planning of his films. (There is still preserved some discarded film footage taken on a Fairbanks set, in which the cameraman began grinding ahead of time, revealing Fairbanks gloomy and scowling, suddenly switching on the high-powered smiling personality). And the solemn child who never smiled until his third birthday remained in another corner of Fairbanks’ soul forever too.

With his restless energy demanding outlet, and with his incurable passion for showing-off, it was inevitable that he soon acquired a passion for the stage, and more to keep him out of mischief than for any other reason, his mother sent him to a local dramatic school. When he was 17, in the year 1900, he did what hopeful actors usually do: he went to New York. After five eyars of bit parts, non-theatrical jobs, and even a cattle-boat trip to Europe, he was discovered by the New York theatrical producer, William A. Brady, who saw his possibilities for light comedy and gave him an important role in A Case of Frenzied Finance (Savoy Theatre, April 3, 1905). The play folded after eight performances; but Douglas Fairbanks proved himself to Brady’s satisfaction, and thereafter he was in. Not immediately a star, of course, but on the way to becoming one.

From the date to the end of his stage career, Fairbanks appeared in the following plays (all New York except as noted:

A Case of Frenzied Finance (April 3, 1905)

As Ye Sow (toured 1905-06; played one month in New York)

Clothes (Sept. 11, 1906; 113 performances)

The Man of the Hour (Dec. 4, 1906; 479 performances)

All for a Girl (Aug. 22, 1908; his first starring role)

A Gentleman from Mississippi (Sept. 29, 1908; ran “over a year”)

The Dub

The Lights of London

A Gentleman of Leisure (fall, 1911)

A Regular Businessman (Vaudevill sketch)

Officer 666 (1912; Chicago company only)

Hawthorne of the U.S.A. (Nov. 4, 1912)

The New Henrietta (Dec. 26, 1913, after a tour that included Toronto)

He Comes Up Smiling (Sept. 16, 1914; 61 performances)

The Show Shop (Dec. 31, 1914; last performance: May 15, 1915)

Long after the end of the run of The Show Shop, Fairbanks had signed a contract with the Triangle Film Corporation, and as soon as he was free of commitments he and his wife and young son left for Hollywood. He was then 32 years old.

The Triangle company had just recently been formed by the banding together of the production companies of D.W. Griffith, Mack Sennett and Thomas Ince. Fairbanks’ first film for them was The Lamb, an adaptation of his stage success, The New Henrietta. The ebullient, irresponsible Fairbanks, whose excess energies were perpetually spilling over into almost unceasing athletic displays–on-camera as well as off–did not appeal to Griffith, who was supervising the production of The Lamb; Griffith seriously felt that Fairbanks would do much better under Sennett,–a suggestion that didn’t appeal to Fairbanks, who considered he was demeaning himself sufficiently by appearing in pictures at all. Fortunately, some shrewd person or persons saw to it that he got together with two other Triangle employees: scenario writer Anita Loos (writer of The New York Hat and future author of the novel Gentlemen Prefer Blondes) and director John Emerson, who soon saw how the exuberant Fairbanks off-stage personality could be exploited on the screen.

Much to everyone’s surprise, The Lamb proved a hit, and Fairbanks was turned over to the Loos-Emerson team, which produced 12 films in as many months, to the end of 1916. So popular were these films that by that time Fairbanks was drawing a salary of $10,000 a week. But even this wasn’t enough for him, so instead of renewing his contract with Triangle, he and his brother formed the Douglas Fairbanks Corporation to make his own films and thus keep all the profits himself. The films were released by Famous Players-Lasky under their Artcraft label. From Triangle he brought his collaborators, John Emerson and Anita Loos, and (working at a slower pace) they turned out another 12 pictures over the next two years. In 1919 Fairbanks, Pickford, Griffith and Chaplin (“the Big Four”) formed their own distributing company, United Artists Corporation, which handled all their films thereafter.

In the five years from his entry into films till the summer of 1920, Fairbanks made 29 films (most of them, though not all, written by Anita Loos and directed by John Emerson) which were, in in general, simply variations on a single theme: the brash, enthusiastic young “100% American”, brimming over with vigor and optimism and know-how,–“Mr. Average Man with the powers of Superman”–triumphing over all obstacles. So suitable was this formula to his personality, and vice versa, and to the times, that by 1920 he was one of the most loved stars of the screen, not simply in America but all over the world. In March of that year he married the screen’s most popular actress, Mary Pickford, a romance enthusiastically endorsed by the delighted public, (who didn’t seem in the least to mind that both had had to divorce their current mates to make it possible). Their honeymoon in Europe was like a Royal Tour.

Then, in the summer of 1920, Doug suddenly took a big chance and tried a new type of film: a costume romance, The Mark of Zorro. So unsure was he of its reception by the public that when it was finished but before it was released, he hurriedly made the 30th film in the tried-and-true formula, The Nut. But The Mark of Zorro proved to be far and away his most popular film to date,–and so for the rest of the silent era, Fairbanks produced nothing but big costume pictures, at the rate of no more and frequently fewer than one a year. The last was The Iron Mask (1929), in which he said farewell to the screen character the public had loved. He was by now 46 years old.

For years the fans had been clamouring for Doug and Mary to make a picture together; but when they finally did, The Taming of the Shrew proved not to be the picture the public wanted. His few remaining films were received with similar apathy (and made, it is reported, with similar lack of enthusiasm on his part). In 1934 he made a film for Alexander Korda, The Private Life of Don Juan, and then no more.

All his life Douglas Fairbanks had worshipped youth, and with the passing of his own, a pitiful demoralization set in. His frantic restlessness wrecked his marriage with Mary Pickford,–a blow to their fans from which neither recovered,–and in 1936 he married Lady Sylvia Ashley. Although making no more films, he continued to lead a strenuously active life in Hollywood, in spite of warning signals,–and eventually a coronary thrombosis ended his life on December 12, 1939, at the age of 56.

Notes by Fraser Macdonald

Here is a complete list of all Douglas Fairbanks’ films, with release dates (approx):

Produced by Triangle Film Corporation:

1915:

The Lamb (Sept. 23, 1915)

Double Trouble (November)

1916:

His Picture in the Papers (Feb.)

The Habit of Happiness (March)

The Good Bad Man (April)

Reggie Mixes In (June)

Flirting with Fate (June)

The Half-Breed (July)

The Mystery of the Leaping Fish (Aug.)

Manhattan Madness (Sept.)

American Aristocracy (Nov.)

The Matrimaniac (Dec.)

The Americano (Jan. 1917)

Produced by the Douglas Fairbanks Corp.

(a) Released by Famous Players-Lasky

1917:

In Again, Out Again (May)

Wild and Woolly (July)

Down to Earth (Aug.)

The Man from Painted Post (Oct.)

Reaching for the Moon (Nov.)

A Modern Musketeer (Jan. 1918)

1918:

Headin’ South (March)

Say, Young Fellow (June)

Bound in Morocco (Aug.)

He Comes up Smiling (Sept.)

Arizona (December)(b) Released by United Artists:

1919:A Knickerbocker Buckaroo (June)

His Majesty the American (Sept.)

When the Clouds Roll By (Jan. 1920)

1920:

The Mollycoddle (June)

The Mask of Zorro (Dec.)

The Nut (March 1921)

The Three Musketeers (Sept. 1921)

Robin Hood (Nov. 1922)

The Thief of Bagdad (March 1924)

Don Qu, Son of Zorro (June 1925)

The Black Pirate (March 1926)

The Gaucho (Nov. 1927)

The Iron Mask (March 1929)

(Sound films):

The Taming of the Shrew (Dec. 1929)

Reaching for the Moon (Jan ’31) (af 1917)

Around the World in 80 Minutes (Nov. ’31)

Mr. Robinson Crusoe (Sept. 1932)

The Private Life of Don Juan (Nov. 1934)

NEXT MEETING: February 10: Wallace Reid in The Dancin’ Fool (with Bebe Daniels) Also: Broncho Billy in Shootin’ Mad.

Leave a Reply