The Toll Gate (1920) and Sky High (1921)

Toronto Film Society presented The Toll Gate (1920) and Sky High (1921) on Monday, February 8, 1965 as part of the Season 17 Monday Evening Silent Film Series, Programme 4.

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

Program No. 4

Monday February 8, 1965

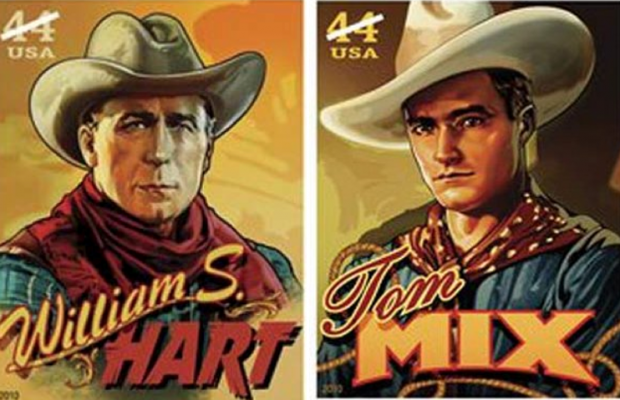

Two WESTERN Stars

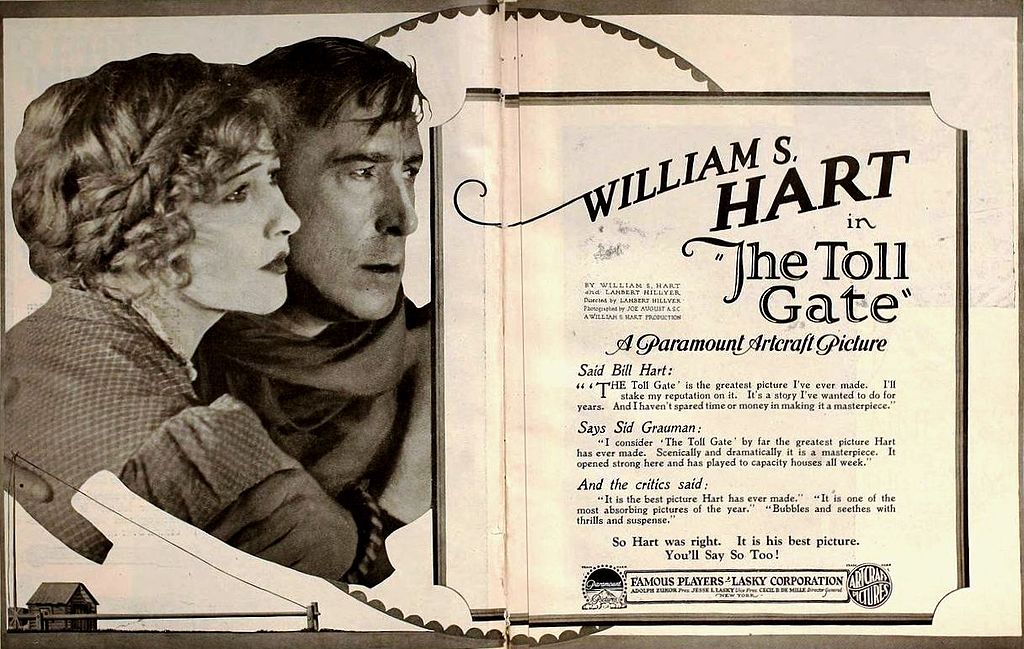

WILLIAM S. HART in…The Toll Gate (1920)

Produced by the William S. Hart Co. for Paramount-Artcraft

Director: Lambert Hillyer

Story: Lambert Hillyer and William S. Hart

Photography: Joseph August

Copyright: William S. Hart Co.; 1 April 1920 (6 reels)

Cast:

Black Deering William S. Hart

Mary Brown Anna Q. Nilsson

Jordan Joseph Singleton

Sheriff Jack Richardson

“The Little Fellow” Richard Hendrick

INTERMISSION

Tom Mix in…Sky High (1921)

Produced and released by Fox Film Corporation

Direction, story and scenario: Lynn Reynolds

Photography: Daniel B. Clark

Copyright: William Fox; January 15, 1922 (5 reels)

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

Contrary to the impression that many film histories tend to give, the “Western” was not the creation of the cinema. Long before movies were invented, plays and novels had been exploiting and feeding the public fascination with stories of frontier life and the Great Open Spaces. But the newly-born motion picture lost little time in getting into the act; and it soon surpassed its models, for in addition to combining the mobility of the novel with the vividness of visible actors, it provided the thrilling background of the genuine outdoors. When film makers eventually began filming in the actual West, the majestic scenery lent epic grandeur to even the tritest cowboys-and-rustlers yarn.

Film Westerns didn’t really hit their stride until G.M. Anderson began producing them in the new California studios of his own company, Essanay, in 1908, and supplied what he realized the crude Westerns (including The Great Train Robbery) had hitherto lacked: a protagonist, or “hero”. As it happened, he couldn’t find an actor to play the lead in his first such film, and out of sheer desperate necessity (for he couldn’t so much as ride a horse) he played the part himself. The film was an immediate success, so he promptly carried on with a whole series all about the same character: Broncho Billy. Thus Anderson became the first Western star in cinema history. His knowledge of the West was derived solely from pulp fiction, but as writer-director he had the story-teller’s gift. He knew how to tell a rattling good yarn, full of action and plenty of chases; and in the hundreds of Broncho Billy pictures he turned out at the rate of one a week (they were all shorts, like most films in those days) he laid down most of the precedents, the classic rules of Westerns that are still respected today. (Anderson, by the way, is still living.)

Naturally, the popularity of Essanay’s Broncho Billy films spawned Westerns from most of the other studios (Tom Mix got started during this period), and many excellent ones were produced by both D.W. Griffith and Thomas Ince. Even European film studios were turning out Westerns. And as usual, they all overdid it, with the inevitable result that around 1913 the vogue waned drastically,–and from all accounts, deserved to. And this is where our story begins.

WILLIAM S. HART (1870-1946)

The man who, single-handed, rescued the Western film from the rut of mediocrity into which it had fallen was William S. Hart, in a career that spanned slightly more than ten years. As an actor, director, and to a lesser degree as a writer, he brought to the Western both realism and a rugged poetry. His films, the motion picture equivalents of the paintings of Frederic Remington and the drawings of Charles M. Russell, represent the very heart and core of that which is so casually referred to as Hollywood’s “Western tradition”.

(Opening paragraph of Chapter 5: William Surrey Hart and Realism, of The Western by Fenin and Everson)

William Surrey Hart was born in Newborough, New York, on December 6, 1870, and when he was quite young his father, who was a miller, moved the family out to the West, eventually settling just outside a Sioux Indian reservation in the Dakotas. As a boy, Hart played with the Indian children, learned their language and customs, and never lost his love for them. While still an adolescent he worked as a trail-heard cowboy in Kansas, and once had the alarming experience of being caught in the crossfire of a sheriff and two gunmen on the streets of Sioux City. (Movies and TV, it seems, didn’t invent these things after all!)

Much has been made of Hart’s first-hand knowledge of the West and the consequent authenticity of his films; but the truth is that he was still only fifteen when he and his family returned to the East. His lifelong passion for the Old West was undoubtedly due to its being his own personal Rosebud; but while his memories of his childhood may well have remained very vivid, one is tempted to wonder how accurate they were. However, he undoubtedly supplemented his memories with a great deal of research, like any hobbyist with a passion for his subject; and anyhow, how many other makers of Westerns have had even that much first-hand acquaintance with Western life in the early 1880’s?

After his return east he worked at odd jobs for several years until he became stage-struck and took up acting. His first professional appearances were in Shakespearean roles, (and in the short speech he recorded for the sound camera in 1939 as a prologue to a reissue of Tumbleweeds he still sounds like an old Shakespearean actor). In 1899 he was in the original cast of a Broadway smash hit: the stage version of Ben Hur, in which he played Messala,–a role that kept him busy for several years. After the last chariot race was run he went through another lean period before he entered still another phase of his stage career by appearing in various Western dramas, such as The Virginia and The Squaw Man.

Of all the stage stars who went into film at that period, Hart was probably the only one who did so not reluctantly, swallowing his pride out of sheer economic necessity, but because he was actually anxious to make films. What happened was that he went one day to see a Western movie and was so appalled by its inaccuracies that he conceived the ambition to make Western films himself, to show people what the West was really like. Fortunately for him, he discovered that an old actor pal of his, Tom Ince, had now become an important movie producer out in Hollywood, in partnership with D.W. Griffith and Mack Sennett, and Hart had only to ask and it was all arranged, in spite of Ince’s misgivings that Westerns had become a drug on the market. Thus, in the summer of 1914, did William S. Hart enter films at the age of 44.

His first two films were shorts, in which he played villains; then he was starred in two features: The Bargain (written by himself) and On the Night Stage, and these proved such hits that Ince promptly signed him to a contract as a director-actor. Thereafter Hart directed most of the films he made for Triangle Pictures,–shorts at first, while he learned his craft, then features exclusively. When he moved to Famous Players-Lasky (Paramount) in 1917, he took with him most of his own crew, including his cameraman, Joe August (who later shot The Informer and other John Ford films), and one of his writers, Lambert Hillyer, who thereafter directed most (25 out 27) of the films he made for this company between 1917 and 1924, (and doubled for Hart in many of the more dangerous stunts).

Tonight’s film, The Toll Gate, considered to be among his four or five best films (others would include Hell’s Hinges, The Aryan, The Testing Block and The Return of Draw Egan), is also very representative, as it is based on the theme that obviously appealed to Hart, for he used it in so many of his films: the outlaw who reforms through his love for a good woman.

But it is only fair to report that Hart did not always stick to type. A few of his films were not Westerns at all; and one picture, The Captive God, is set in Aztec times. One of his better pictures is a delightful but untypical quasi-Fairbanks comedy, Branding Broadway. And in Three Word Brand he played three different (and differentiated) roles: the hero, his brother, and his father.

But by and large, most of Hart’s films were realistic Westerns in which he played Good Bad Men. Unfortunately, as time went on the sentimental streak in him began to get out of hand; and his films became slower and heavier, for he steadfastly refused to introduce action for its own sake. (Tom Mix, over on the Fox lot, had no such scruples, and the public was showing an understandable preference for the livelier Mix films). After his 25th film for Paramount (Travelin’ On, March 1922), Hart retired for over a year, then came back and made two more: Wild Bill Hickok and Singer Jim McKee, to the latter of which was such a linker that Adolph Zukor ordered him to submit to supervision. Hart refused to compromise, and left the company. For United Artists he made Tumbleweeds (1925), a big-budget epic which, in spite of its flaws, was in many respects one of his best. But the public barely returned him his production costs; so once again he retired, this time forever. He settled on his ranch at Newhall, California, and wrote books, including his autobiography, My Life East and West (1929). Two tentative arrangements to return to the screen came to nothing; and he died on June 23, 1946. By the terms of his will, his ranch has been opened to the public as a museum.

* * *

TOM MIX (1880-1940)

If William S. Hart brought stature, poetry and realism to the Western, Tom Mix unquestionably introduced showmanship, as well as the lick, polished format that was to serve Ken Maynard and Hoot Gibson in the Twenties and Gene Autry and Roy Rogers in the Thirties. His influence as such outlived that of Hart in the long run.

(Opening paragraph of Chapter 6: Tom Mix and Showmanship, from The Western by Fenin and Everson)

Tom Mix was born at Mix Run, Clearfield County, Pennsylvania, on January 6, 1880; like Hart, an Easterner by birth, but in many ways far more the real thing than Hart was. His pre-film real-life story sounds far more exciting than any movie he ever appeared in. In his teens he joined the U.S. Army and fought in the Spanish-American War, the Philippine insurrection, and in China during the Boxer Rebellion. When he left the Army, he broke horses for shipment to the British Army in the Boer War, and accompanied a cargo of them to South Africa, where he stayed on for awhile as a wrangler. Returning to America, he went out West and became a cowpuncher in Texas, Oklahoma and Kansas, and joined one of the more famous Wiild West shows of the day. In 1909 he was champion prize winner in the rodeos at Prescott, Arizona, and Canon City, Colorado. During this period he also saw duty as a Texas Ranger, as a sheriff in Kansas and Oklahoma, and as a deputy U.S. Marshall in eastern Oklahoma, and in new Mexico he rounded up and captured the notorious cattle rustlers, the Shont Brothers.

Then he bought himself a ranch in the Cherokee territory of Oklahoma, married (for the third time), and prepared to settle down. A motion picture outfit, the Selig Company of Chicago, rented his ranch to make a documentary film, and hired him as general adviser, in charge of the cowboys and of controlling the animals when needed. When this brief foretaste of his future was ended, he went down to Mexico, where the Revolution had broken out, and joined Madero’s forces, and narrowly escaped death in front of a firing squad. When he got back home he learned that Selig had been looking for him, wanting his animal-controlling services for as a series of jungle adventure pictures they were doing. So off to Chicago he went and joined the Selig company, and presently found himself working in front of the cameras as well, both in Chicago and in the company’s California studios. Thus, between 1911 and 1917, Tom Mix turned out nearly a hundred films (shorts) for Selig,–comedies and Westerns, many of which he wrote and directed himself in addition to playing the starring role. That they weren’t terribly good is hardly surprising, considering the lack of qualifications Mix started out with; but they got better as he went along, and gave him valuable experience which paid off when in 1917 William Fox signed him to a starring contract to make Westerns. Hitherto he had been only a minor star; now at 37 his real career began—to the mutual benefit of both Fox and Mix for the next ten years, by the end of which period Mix was drawing a salary of $20,000 a week, which is comfortable living.

Mix’s fantastic rise to popularity was partly due to the shrewd decision not to make him a second Hart. His films were never prestige pictures; they were aimed frankly at the juvenile market (whereas Hart’s films were pretty much “adult Westerns”), and were breezy and cheerful, with plenty of comedy elements, and plenty of opportunities for stunts—most of which he did himself, rarely using doubles. “Mix’s screen character never drank, swore, or even used violence without due cause. His scripts usually saw to it that he was never required to kill a villain, or even wound him if it could be avoided. Instead, he would capture and subdue them by some elaborate lasso-work, or by some fancy stunts. His idealized Western hero, possessed of all the virtues and none of the vices, helped usher in the code of clean-living, non-drinking, and somewhat colorless stagebrush heroes, a code that remained in force until the early Fifties, when Bill Elliott, playing the tough Westerner characterized by Hart, began to restore the balance to a more realistic level” (The Western). Modern parents must surely long for another Tom Mix.

Most of Mix’s pictures were made on location, deliberately to take advantage of the various scenic wonders of the American west, with Colorado being a special favorite with him (Sky High was filmed in the Grand Canyon). In this he was abetted by his cameraman, Dan Clark, wo filmed most of Mix’s Fox films, contributing in no small way to their success. (Two of Mix’s films, by the way, were directed by John Ford: Three Jumps Ahead and North of Hudson Bay).

Most of Mix’s pictures were made on location, deliberately to take advantage of the various scenic wonders of the American west, with Colorado being a special favorite with him (Sky High was filmed in the Grand Canyon). In this he was abetted by his cameraman, Dan Clark, wo filmed most of Mix’s Fox films, contributing in no small way to their success. (Two of Mix’s films, by the way, were directed by John Ford: Three Jumps Ahead and North of Hudson Bay).

Unfortunately, only two of Tom Mix’s films escaped extinction in the disastrous fire that destroyed so many valuable prints and negatives stored in the Fox vaults; but at least one of these, Sky High, is at typical example of the many films that made Tom Mix such a popular and profitable star during the 1920’s. Notice, by the way, that he does his own stunts in this film: the camera works close enough to him t prove it. (The other surviving film, Riders of the Purple Sage, is unfortunately less representative, being sombre and austere and more in the style of Hart than a typical high-spirited Tom Mix vehicle).

Around 1928 Mix left Fox and went to FBO, a small company that specialized in Westerns. In the early thirties he “retired” and joined the Sells Floto Circus, which paid him handsomely, and he got married (for the fifth time) to a trapeze artist. Universal brought him back to the screen for several excellent sound Westerns, including the first Destry Rides Again and a film with Mickey Rooney, My Pal the King (1932). In 1935 he made a serial for Mascot, The Miracle Rider, which proved to be his last film, and then he went out on the road again with Tom Mix Wild Animal Circus. True to the pattern of adventurous life that had begun in his youth, Tom Mix died with his boots on; he was killed in an automobile accident on October 12, 1940, near Florence, Arizona.

* * *

The differences between Hart and Mix are rather interesting. Hart was a very sentimental man, and because of his nostalgic love for the old West which he had known in his childhood, he devoted himself to recreating it on the screen with accuracy and realism. Mix, a breezy extrovert, never knew the West until he was in his twenties, but thereafter he probably knew it first-hand a great deal better than Hart did; but because it was merely a way of life with him, and because he went directly from this life into film making, he had no nostalgic attitude toward it. He was content to entertain people with tall tales about it. He was a showman, and movies were just another form of Wild West Show, and a lot more fun than the real thing. The sumptuous splendour of Mix’s palatial estate in California, his collection of fancy boots and costumes, may not sound like a typical cowboy; but no cowboy with Mix’s income is typical! Both Hart and Mix were genuine, each in his own way, and their screen selves complement each other; and the films were the richer for them both.

(Readers interested in this whole subject should read The Western by Fenin and Everson (1962), from which most of the foregoing notes have been shamelessly scribbed, as will be apparent to anyone who compares the two texts,–just as a similarly interesting comparison can be made of the text of their chapter on Hart and that of George Mitchell’s article on Hart in the April 1955 issue of Films in Review).

Notes by Fraser Macdonald

Next show: March 8: Harold Lloyd in Never Weaken & William de Mille’s Miss Lulu Bett with Lois Wilson and Milton Sills (1921).

Leave a Reply