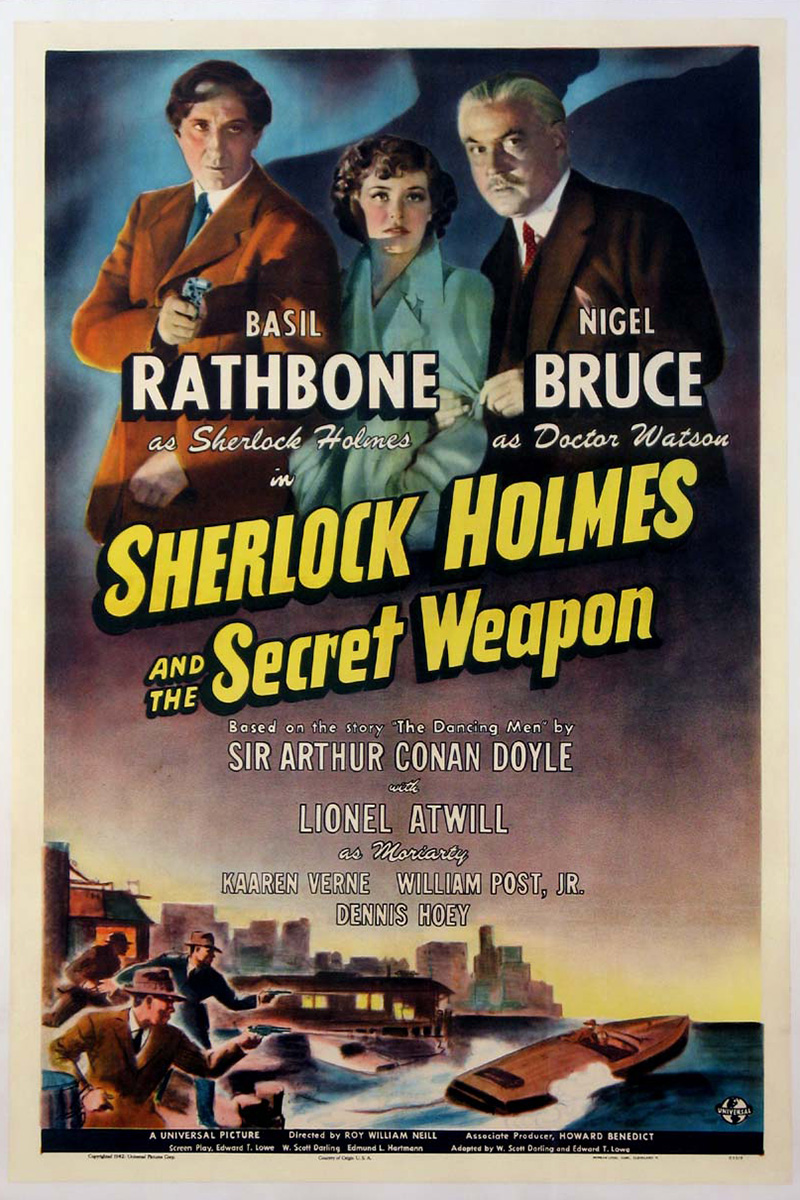

Sherlock Holmes and the Secret Weapon (1942)

Toronto Film Society presented Sherlock Holmes and the Secret Weapon (1942) on Sunday, October 22, 2017 in a double bill with The Scarlet Pimpernel as part of the Season 70 Sunday Afternoon Film Buff Series, Programme 2.

Production Company: Universal Pictures. Associate Producer: Howard Benedict. Director: Roy William Neill. Screen Play: Edward T. Lowe, W. Scott Darling, and Edmund L. Hartmann, inspired by the short story The Adventure of the Dancing Men by Sir Arthur Conan Doyle in Strand (Dec.,1903). Cinematography: Les White. Art Direction: Jack Otterson and Martin Obzina. Film Editor: Otto Ludwig. Set Decorations: Russell A. Gausman and Edward R. Robinson. Music Director: Charles Previn. Sound Recording: Bernard B. Brown. Release Date: January 4, 1943.

Cast: Basil Rathbone (Sherlock Holmes), Nigel Bruce (Dr. John H. Watson), Lionel Atwill (Professor Moriarty), Kaaren Verne (Charlotte Eberli), William Post, Jr. (Dr. Franz Tobel), Dennis Hoey (Inspector Lestrade), Holmes Herbert (Sir Reginald Bailey), Mary Gordon (Mrs. Hudson).

Sir Arthur Conan Doyle wrote the Holmes stories, beginning with A Study in Scarlet in 1886, followed by a total of 56 stories and four novels, with Holmes’ techniques of observation and deduction apparently based on one of his teachers at Edinburgh University. The character became an instant success all over Europe and the United States and probably remains one of the best-known fictional creations ever. But Conan Doyle had ambitions to be a more “serious” novelist and became more interested in writing historical novels and attempted to kill Holmes off in 1893, but public protest forced him to “resurrect” him, first in the novel The Hound of the Baskervilles in 1901 and then in further stories. His best known non-Holmes books are the early science fiction novels The Lost World and The Valley of Fear. The first films based on Holmes in the early 1900s were made in Germany, Denmark, France, Russia and Hungary rather than Britain or the USA. The first American film, in 1916 was scripted by and acted by William Gillette and the best known silent film, simply called Sherlock Holmes, starred John Barrymore in 1922. These were followed by several cycles of films, notably in the 1940s, with 14 films starring Basil Rathbone as Holmes and Nigel Bruce as Watson, some of them set in the present day rather than the Victorian period, and these are often considered definitive. The Granada TV series between 1984 and 1994, starring Jeremy Brett and keeping the Victorian setting, are also admired. The current favourite Holmes is Benedict Cumberbatch in a contemporary world and as a somewhat arrogant and ultra clever character.

Introduction by Graham Petrie

In the generations since the tales of Sir Arthur Conan Doyle’s Sherlock Holmes were first committed to celluloid, many actors have stepped into the interlocked roles of the peerlessly brilliant master sleuth and his physician ally and Boswell, Dr. John Watson. Inarguably, the most enduring such characterizations remain those of Basil Rathbone and Nigel Bruce, who first ventured into the London fog in the 20th Century-Fox productions of The Hound of the Baskervilles (1939) and The Adventures of Sherlock Holmes (1939). In search of a successful franchise, Universal Studios subsequently acquired the Holmes film rights from the Conan Doyle estate, and then procured Rathbone and Bruce’s continuing services. However, Universal passed

on presenting Holmes in a Victoria-era context, as did the Fox features. Opting instead to stir patriotic fervor on both sides of the Atlantic, the great detective was shifted to a contemporary context, where his deductive prowess could be pitted against the Axis war machine. The second Holmes film made under Universal aegis, Sherlock Holmes and the Secret Weapon (1942), shows the most familiar elements of the studio’s formula for the series, from the performances of the leads to the flag waving motifs, to their best effect.

There are various trademark aspects of the Universal Holmes series that made their bow in Sherlock Holmes and the Secret Weapon. It was the first installment directed by Roy William Neill, who would go on to helm the ten sequels that followed over the next four years. “Neill and his crew of writers and technicians seem to wrest as much well-constructed story and production value from their Holmes stories as could be seen in much bigger budgeted films,” Ron Haydock observed in Deerstalker! Holmes and Watson on Screen (Scarecrow Press). The film also cast Dennis Hoey in his first appearance as Inspector Lestrade, the blustering cop who’s always a few steps behind Holmes’ case-breaking discoveries.

The venerable screen villain Lionel Atwill is much more than serviceable as Moriarty, deliciously evil in his execution of the denouement’s death trap. Cornered, with reinforcements still moments away, Holmes seeks to buy time by taunting his nemesis’s intentions to do away with him by so pedestrian a means as gunfire. The Professor buys into Holmes’ suggestion of gradual bloodletting as the most sadistic means of murder. It’s fairly astonishing that Atwill’s reference to Holmes’ drug usage—“The needle to the last, eh, Holmes?”—made its way past the censors; in the novels, it was merely one aspect of Holmes’ often enigmatic personality.

Best of all, of course, are the efforts of the two leads that kept the film and the very series afloat. Rathbone’s handle on the character—cunning, imperious, implacable, preternaturally observant—led to a connection with the role that the versatile performer came to regret, and he would never recover the career heights he knew after he determinedly walked away from 221B Baker Street, in 1946. Bruce’s semi-comic take on Watson would never endear him to Conan Doyle purists, but his palpable chemistry with his old friend Rathbone appealed to the movie going public.

As Rathbone declared in his autobiography, In and Out of Character, “There is no question in my mind that Nigel Bruce was the ideal Dr. Watson, not only of his time but possibly of and for all time…. It has always seemed to me to be more than possible that our ‘adventures’ might have met a less kindly public acceptance had they been recorded by a less lovable companion to Holmes than was Nigel’s Dr. Watson, and a less engaging friend to me than was ‘Willy’ Bruce.”

Sources: Steinbrunner and N. Michaels: The Films of Sherlock Holmes, Citadel Press, Secaucus, N.J., 1978, TCM Movie Database

Notes by Peter Poles

Leave a Reply