Targets (1968) and Daisy Miller (1974)

Toronto Film Society presented Targets (1968) on Monday, December 7, 1981 in a double bill with Daisy Miller (1974) as part of the Season 34 Monday Evening Film Buffs Series “B”, Programme 5.

Targets (1968)

Production Company: Saticoy/Paramount. Producer: Peter Bogdanovich. Director: Peter Bogdanovich. Screenplay: Peter Bogdanovich, based on the story by Peter Bogdanovich and Polly Platt. Photography: Laszlo Kovacs. Art Director: Polly Platt.

Cast: Boris Karloff (Byron Orlok), Tim O’Kelly (Bobby Thompson), Nancy Hsueh (Jenny), James Brown (Robert Thompson), Sandy Baron (Kip Larkin), Arthur Peterson (Ed Loughlin), Mary Jackson (Charlotte Thompson), Tanya Morgan (Ilene Thompson), Monty Landis (Marshall Smith), Peter Bogdanovich (Sammy Michaels).

Daisy Miller (1974)

Production Company: Copa De Oro, for Paramount, A Directors’ Company Presentation. Producer: Peter Bogdanovich. Director: Peter Bogdanovich. Screenplay: Frederic Raphael, based on the story by Henry James. Photography: Alberto Spagnoli. Editor: Verna Fields. Art Director: Ferdinando Scarfiotti. Music: excerpts from the works of J.S. Bach, W.A. Mozart, Johann Strauss, Boccherini, Haydn, Schubert, Verdi.

Cast: Cybill Shepherd (Daisy Miller), Barry Brown (Frederick Winterbourne), Cloris Leachman (Mrs. Ezra B. Miller), Mildred Natwick (Mrs. Costello), Eileen Brennan (Mrs. Walker), Duilio Del Prete (Mr. Giovanelli), James McMurtry (Randolph Miller), Nicholas Jones (Charles), George Morfogen (Eugenio).

These two films of Peter Bogdanovich’s, the earlier not yet fifteen years old, may seem an odd choice for a Film Buffs’ evening. But Bogdanovich himself is an excellent example of the film buff–in the highest sense of the term–at work in the film industry. He belongs to that group of American filmmakers now at or near forty, who went constantly to the movies before television cut off the whole of the next generation in its flower; who went on to study film in the universities, and who finally made films themselves. Directors like Martin Scorsese, William Friedkin, George Lucas, Brian De Palma, and Francis Ford Coppola; directors who make their films in the full awareness of what has gone before. If such a literary work as T.S. Eliot’s The Waste Land quotes widely but just as purposefully from their predecessors. Obviously older directors did this too, but only in this academic generation of young Americans has “intertextuality” become a clearly distinct way of making films. De Palma’s statement about the art of filmmaking contained in his recent Blow Out depends upon Antonioni’s speculations on the relation between photography and life in his Blow Up; and when Coppola shows us helicopters strafing a Vietnamese village to the strains of the Ride of the Valkries, it helps to recall Griffith’s Klan riding to those same strains in The Birth of a Nation, as well as Marlene’s triumphant blitz of the Russian court at the climax of Von Sternberg’s The Scarlet Empress.

Bogdanovich is in fact a self-educated buff: he did not even go to college, but seems to have spent most of youth in New York movie-houses. After studying acting with Stella Adler and playing for some years off Broadway, he sat at the feet of Andrew Sarris of the Village Voice before going on to write several monographs in the early ’60s which implicitly supported the auteur theory of film direction: monographs on directors such as Hawks, Hitchcock, John Ford, Allan Dwan. His first major working role in film was as assistant director to a famous purveyor of cult horror, Roger Corman. At the end of 1967, Corman was owed several days of work by Boris Karloff, and he also wanted to use up some eighteen minutes of out-takes from his 1963 film The Terror. His assignment for Bogdanovich: make a film using Karloff and the outtakes, and don’t spend more than $125,000. The creative response of the young film buff was to captialize on the iconic qualities of Karloff, whose last significant film this was to be, and who is cast in it as an aged horror star who is quitting the movies because an age of mindless violence has turned him into a figure of high camp. As the young director trying to persuade him to make another movie, Bogdanovich cast himself. In a parallel plot, based on the Charles Whitman killings from the Texas tower in 1966, a young sniper who has Karloff in his rifle sights at the beginning of the picture confronts him once more at the end, in a drive-in where the old actor’s last film is being shown. The old man, turning away from his profession because fictional violence can no longer match the daily fact, faces down the young man, whose violence is so much a part of the daily horror. A comment on a violent contemporary world, but made in characteristically cinema-historical terms.

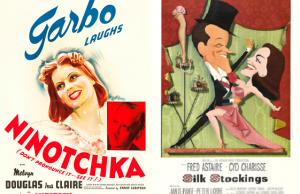

It was Bogdanovich’s second fiction film, The Last Picture Show, which gave him his greatest critical and popular success to date. This black and white film is a recreation of the early 1950s very much in the manner of John Ford: perhaps its most striking performance–a historical quotation–is that of Ben Johnson, who had appeared in two Ford films, as well as George Stevens’s famous western Shane. Paper Moon, What’s Up, Doc? is an even clearer one to Hawks and the whole age of screwball comedy; Nickelodeon, based on the oral reminiscences of Dwan and others, is a tribute to the earliest days of the movies, and its climactic moment is the first performance of The Birth of a Nation. But Bogdanovich’s reputation and popularity have declined precipitously since The Last Picture Show, and reviews have often been vitriolic. James Monaco has called At Long Last Love “one of the more embarrassing displays since the advent of talkies,” and Richard Corliss, reviewing his most recent film, They All Laughed, headlines it as an “aimless bust.”

While much recent depreciation of Bogdanovich is that of carping critics retreating from earlier over-praise, many of Bogdanovich’s wounds are certainly self-inflicted. His sophomoric appearances on talk shows, his adolescent trailers, his casting of his girl friend Cybill Shepherd in roles beyond her reach, have all helped to bring him down. But Daisy Miller is, on balance, one of the most successful translations of Henry James (an author notoriously intractable to visual presentation). Though the casting of Cybill Shepherd as Daisy provoked a reaction only less adverse than the one Daisy herself provoked a century earlier (“an outrage on American girlhood,” one critic called her then), she is in fact a perfect visual equivalent for James’s “common,” “uncultivated” heroine (“in her light, sweet, superficial little visage there was no mockery, no irony”). Even her Texas twang works better in 1974 than a Schenectady sound, which was James’s reductio ad absurdum of provincialism for his day. And her ineptitudes as an actress happily convey the essential gaucherie and brashness of the character.

While Targets has only one notable actor in it–a quotation from over a hundred horror films, several of which appear along with him–by the time of Daisy Miller Bogdanovich, like most creative directors, had gathered a troupe of co-workers around him. Mildred Natwick, who had played amiably dotty offshoots of patrician New England families in The Late George Apley and The Trouble With Harry, here plays the tree in full bloom, the censorious American aristocrat abroad. That versatile actress Eileen Brennan plays here another of those indefinably vampirish Europeanised Americans whom James regarded as much more pernicious than the true European decadent. And Cloris Leachman expertly carries over her special brand of slightly scatty vulgarity as Daisy’s mother. The one weak performance is that of Barry Brown. Winterbourne broods over James’s novel, which is ultimately as much about his masculine failure as her feminine overreachment. While the camera coincides with his vision at moments (the early high-angle shot as Daisy and Giovanelli walk in the courtyard, under Winterbourne’s disapproving eye), the same camera alienates us from the figure who is supposed to be our guide by its visual presentation of him. James’s Winterbourne should look like the young Dirk Bogarde with some of the experience of having played Aschenbach; this Winterbourne looks like a youthful American of the 1960s bumming across Europe on $1000 a day. With James, point-of-view, the consciousness of the central midn, is of absolue importance. Film can manage this only with great difficulty; only Truffaut, whose image of himself, shot through a distorting glass door as he hides from and observes the heroine of The Green Room, must now stand as perfect visual paradigm for Jamesian point-of-view, has really accomplished this.

In adapting Daisy Miller, Bogdanovich clearly had a good deal of help from his scriptwriter, Frederic Raphael, who had won an Academy Award for an earlier treatment of innocence-in-decadence, John Schlesinger’s Darling (1965), had explored the theme further in his version of Iris Murdoch’s A Severed Head (1971), making along the way an excellent novel-into-film translation of Hardy’s Far From the Madding Crowd (1967–also for Schlesinger).

So here is a unique opportunity to see two not very well known films of a director who began as one of Hollywood’s Wunderkinder and who has now been relegated to a place amongst more self-indulgent Kinder. Bogdanovich before the bust; before the critics really took aim at him.

Notes by Barrie Hayne

Leave a Reply