The Philadelphia Story (1940) and High Society (1956)

Toronto Film Society presented The Philadelphia Story (1940) on Monday, July 13, 1981 in a double bill with High Society (1956) as part of the Season 34 Summer Series, Programme 1.

The Philadelphia Story (1940)

Production Company: Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer. Producer: Joseph L. Mankiewicz. Director: George Cukor. Screenplay: Donald Ogden Stewart, based on the play by Philip Barry. Art Direction: Cedric Gibbons. Associate: Wade B. Rubottom. Music: Franz Waxman. Photography: Joseph Ruttenberg. Editor: Frank Sullivan. Sound: Douglas Shearer. Set Decorations: Edwin B. Willis. Gowns: Adrian. Hair Styles: Sidney Guilaroff.

Cast: Cary Grant (C.K. Dexter Haven), Katharine Hepburn (Tracy Lord), James Stewart (Mike Connor), Ruth Hussey (Liz Imbrie), John Howard (George Kittredge), Roland Young (Uncle Willie), John Halliday (Seth Lord), Virginia Weidler (Dinah Lord), Mary Nash (Margaret Lord), Henry Daniell (Sidney Kidd), Lionel Pape (Edward), Rex Evans (Thomas), Russ Clark (John).

High Society (1956)

Production Company: Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer. Producer: Sol C. Siegel. Director: Charles Walters. Screenplay: John Patrick, based on the play The Philadelphia Story by Philip Barry. Art Direction: Cedric Gibbons, Hans Peters. Music Supervised and Adapted by: Johnny Green, Saul Chaplin. Music and Lyrics: Cole Porter. Orchestration: Conrad Salinger, Nelson Riddle. Cinematographer: Paul A. Vogel. Editor: Ralph E. Winters. Locations: Newport, Rhode Island. Songs by Cole Porter: “True Love,” “High Society”, “Well, Did You Evah?, “You’re Sensational,” “Who Wants to Be a Millionaire,” “Little One,” “Now You Has Jazz,” “Mind If I Make Love to You,” “I Love Yo, Samantha.”

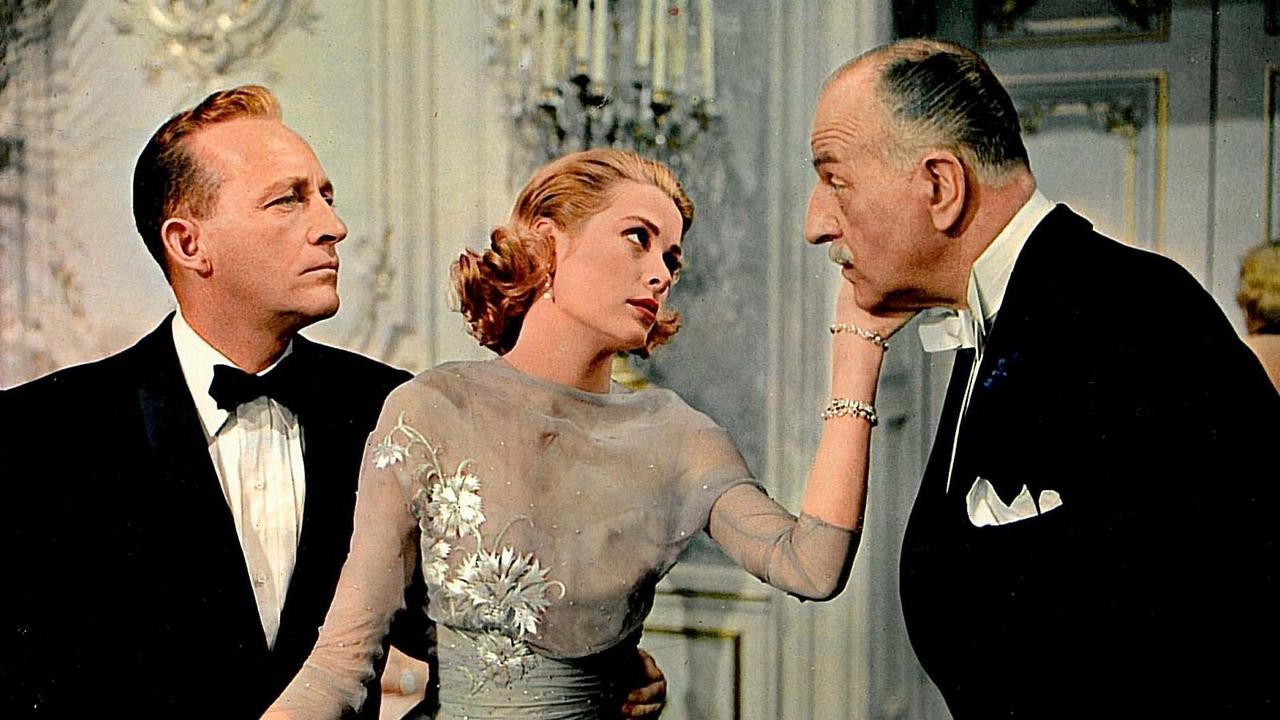

Cast: Bing Crosby (C.K. Dexter Haven), Grace Kelly (Tracy Lord), Frank Sinatra (Mike Connor), Celeste Holm (Liz Imbrie), John Lund (George Kittredge), Louis Calhern (Uncle Willie), Sidney Blackmer (Seth Lord), Louis Armstrong (Himself), Margalo Gillmore (Mrs. Seth Lord), Lydia Reed (Caroline Lord).

For the first of our “re-visions” this summer, we present George Cukor’s The Philadelphia Story, itself a re-vision of Philip Barry’s very successful Broadway play, and the Charles Walters-Cole Porter musical version, which is based, as the credits say, on the play rather than the earlier film.

We begin, then, with Philip Barry, the most successful exponent of comedy of manners in the American theatre between the two wars; his only rival, in those years, would be Grace Kelly’s uncle, George Kelly, the author of Craig’s Wife. From the late 1920s, before petering out during the war, Barry produced a series of hits: Holiday, Hotel Universe, The Animal Kingdom, and The Philadelphia Story; all, in one way or another, presenting the rich upper classes, as one of Barry’s critics noted, as “the most marvellous people on earth.” Cukor once endorsed this view of the rich, whom he found “reassuring” by their presence alone.

The Philadelphia Story, the film, is a hybrid of genres, following Barry’s play closely as a comedy of manners, yet partaking in the prevailing Hollywood mode of screwball comedy, and starring the principal exponents of that mode, Grant and Hepburn (Cukor had previously made Barry’s Holiday into a film, casting the same pair). The basic subject of both stage and film genres is (to borrow a line from Barry’s play) “the privileged classes enjoying their privileges.” The incarnation of wealth in screwball comedy may often be the fat and laughable Eugene Pallette, and the young and handsome lovers may start out or seem to be poor, but they always end up rich (It Happened One Night, Easy Living, Midnight). Both comedy of manners and screwball comedy love a Lord!

There is some class tension in Barry’s play, but the socialistic comments of the reporter Mike Conner (Stewart, Sinatra) are hardly the voice of Philip Barry, graduate of Yale College. Mike’s socialism, in fact, is much more the victim of his encounter with Tracy than her snobbery is the victim of her encounter with him. The play, and both films, affirm aristocratic values at the end. We need not take too seriously the musical answer to “Who Wants to Be a Millionaire?”–“I Don’t!” The answer in all three works, all ending in marriage, is a plain “I Do!”

Not Mike Connors, and not the scriptwriter Donald Ogden Stewart, can muffle the chorus of adulation of the rich. Stewart was a contemporary of Barry’s at Yale, who unlike Barry got socialist religion and lived long enough to run afoul of Joseph McCarthy. (He also married the like-minded widow of the great reformer Lincoln Steffens; they died last year within a few days of each other). Stewart’s Oscar-winning screenplay for The Philadelphia Story follows Barry’s play very closely; the additional writing is all in Barry’s manner. And there is certainly no reformer’s indictment of the rich.

And John Patrick, educated at Harvard and Columbia, who wrote the script for High Society, sees the rich through glasses no less rosy. He was a successful playwright before he wrote for the screen such sentimental pabulum as Three Coins in the Fountain and Love is a Many Splendored Thing. And of course the true author of High Society may be said to be Cole Porter, also of Yale, the darling of cafe society for over fifty years, and no flaming revolutionary!

As to the two film directors, Cukor is often labelled a “woman’s director”: he continued to direct Leigh and De Havilland after being replaced by Victor Fleming on Gone With the Wind, mainly because Gable would have none of him. Little Women, The Women, Two-Faced Woman, Les Girls, My Fair Lady: the titles alone, taken across his long career, reinforce his claim to the designation. But though he directed Hepburn (as well as Garbo, Crawford, and Shearer) many times, he is more than just a woman’s director. His principal limitation, probably, is he is his theatricality: many of his films, like this one, are adapted from the stage, and they do not always transcend their origins into the realm of true cinema. Charles Walters, on the other hand, was a dancer and choreographer. His films are almost all musicals–Easter Parade, Lili, The Unsinkable Molly Brown–and that is of course the predominant note of High Society, drowning out even what there was of Barry’s acute observation of the privileged at play.

In almost every way, Cole Porter’s music only excepted, High Society is an inferior film to The Philadelphia Story. Katharine Hepburn, whose film career was in decline at the end of the ’30s, but who made a hit in the stage version, and had a firm contract on the part of Tracy Lord in any film adaptation, is replaced by another mainline beauty, Grace Kelly, who may be truer in type to Barry’s “married maiden” or ice goddess, but is wan by comparison to Hepburn’s vibrant performance; the screwball quality is missing. And Cary Grant gives place to Bing Crosby (both born in the same year, though the films are sixteen years apart). As Bosley Crowther noted, Crosby “wanders around the place like a mellow uncle,” and “strokes his pipe with more affection than he strokes Miss Kelly’s porcelain arms.” Frank Sinatra, still on the rise from his comeback in From Here to Eternity, is almost no less superannuated, contrasting with Jimmy Stewart’s engaging youth; Louis Calhern, in his last picture, is no match for Roland Young as ditherer; and Sidney Blackmer is much too saturnine in the roue-father role more insouciantly played by John Halliday. Celeste Holm may be an improvement over Ruth Hussey, though Holm’s own rather aristocratic qualities (she was “Radcliffe” in All About Eve) tend to blur the class conflict point. But surely the greatest character glory of The Philadelphia Story is Virginia Weidler as Tracy’s impish young sister, a role well played, but not nearly as memorably, in High Society. Who could forget her singing (after Groucho the year before) “Lydia the Tattooed Lady”? (In the play, she sings “Pepper-sauce Woman.” Much tamer).

The final reason for the inferiority of High Society might be that whereas Depression audiences enjoyed the vicarious experience of watching the idle rich at play, the audiences of the affluent ’50s no longer found the spectacle endearing. The really memorable performance in High Society may be that of Louis Armstrong, who belongs to neither upper or lower class. Walters and the aging Porter may celebrate the “reassuring” aspects of wealth, but they don’t win for them the total assent of the audience, which is more won over by the seductions of Porter’s songs.

Both these films had their New York openings in the vast cavern of Radio City Music Hall, The Philadelphia Story at Christmas season. Both brought a little happiness into the world, the first at a time when there wasn’t much about, and for that we can be thankful. No one, rich or poor, should leave the theatre tonight depressed!

Notes by Barry Hayne

Leave a Reply